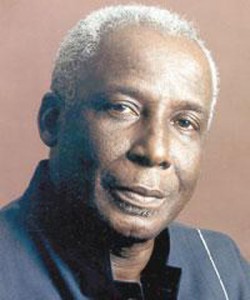

The awesome complexity of Caribbean life and culture, which ranges from language and religion to artistic manifestation in the literary, performing and visual arts, is more than “the binary syndrome of Europe suggests,” University of the West Indies Professor Rex Nettleford has said.

In a presentation at a symposium recently on the subject ‘Expressions of the mind: Philosophy and the Making of the Caribbean Nation’, Nettleford, a Jamaican, quoted Cuban scholar Antonio Benitez Rojos as saying that “Caribbeanness is a system full of noise and opacity, a nonlinear and unpredictable system. In short a chaotic system beyond the total reach of any specific kind of knowledge or interpretation of the world.”

However, the Caribbean’s diversity is also a matter of the mind, which cultivates the spaces that remain invalid, that is beyond the reach of oppression and oppressor. “That very mind also constructs for the intellect and the imagination, a bastion of discreet identities as well as quarries of very invaluable raw material that can be used to build the bridges across cultural boundaries,” Nettleford said. He added that in moments of irrational self-assertion, this could implode into the sort of xenophobia and myriad related obscenities, which caused the United Nations to mount a world conference, albeit controversial as it turned out, on the topic in September 2001, in Durban.

“Carifesta in asserting our Caribbeanness is intended to challenge such obscenities,” he said.

He noted that in the Caribbean so-called great traditions stand side by side and interact with the little traditions. In this regard a folk song, a contemporary reggae tune or calypso could be classical, contemporary modern and ethnic all at the same time. He gave as examples Bob Marley’s “Redemption Songs”, Jimmy Cliff’s “Many Rivers to Cross”, Peter Tosh’s “Jah is my Keeper”, the Mighty Sparrow’s “Jean and Dinah” or “Congo Man”, Lord Kitchener’s “Sugar Boom Boom”, Black Stallion’s “Caribbean” and David Rudder’s “High Mas” as classics in their genres.

Creole languages

Creole languages of the Caribbean are considered languages in their own right, he said, noting that Jamaica boasts a dictionary of Creole from Cambridge University Press and Papiamento is used along with formal Dutch for instruction in Curacao. Creole is the language used for news broadcast sometimes in territories where the French once settled. These languages still have cultural influence. He also cited the poetry of St Lucian Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott; Aime Cesaire of Martinique; Suriname’s poet, the late Martin Dobru; and Nicholas Guillen whose poetry sings with the voice of Cuban Spanish and not Castillian.

He said the distinct Caribbean culture also comes across in the lyrics of the calypsonians, the rhyming quatrains of folklorist and poet Louise Bennett, or, of the story-telling humour of Paul Keans Douglas.

These languages, which he described as “the vehicles of resistance, as ritual or history and humour,” serve their myriad purposes alongside standard English, academy French, metropolitan Spanish and standard Dutch, which the imperial still consider legitimate means of formal or civilized communication in a Caribbean which is arguably the longest colonized region on planet earth ever since Cristobal Colon, “otherwise known as Columbus, discovered that he was discovered by native Americans of the Caribbean in 1492.”

He said that as with language so too is religion in the Caribbean cultural life. Religion, he said, “is an expression of the biblical reminder that in God’s house there are many mansions.”

Religion

He said it was possible for a Caribbean citizen to be baptized as a Roman Catholic, an Anglican, a Methodist or a Presbyterian and still find grace and comfort in santeria, voodoo, pocomania, obeah, revivalism, cumina, shango, cumfa or any other native born or religious expression, in ways that are alien to other cultures.

“You choose your different means to survive,” he said adding that Hinduism, Islam, Orisha worship and new age spiritualism are all legitimate religions today in what was once an exclusive outpost of Christendom. He noted, too that in the Caribbean it is possible for an Indian with indentured labour antecedents to be born into a Hindu family, educated in a Christian school, usually Presbyterian, or Roman Catholic school and later get married to a Muslim.

“Such cultural confusion does not necessarily result in schizophrenia which frequently serves as a source for creative living,” he said as this Caribbean reality was within the reach of most ordinary beings in the region and accounted for the region’s textured diversity.

He said that this phenomenon or philosophy “may well be deeply culturally determined by the historical and existential experiences of the life of contradictions, paradoxes and dialectical relationships and one dominated by centuries of formal rules of engagement not one of one’s own making.”

The magical also co-existed with the scientific and he said it was a small wonder that to many Caribbean people “science means higher science, rooted in the notion of the supernatural and extra-sensory as much as in empirical experience as say in the practice of traditional medicine based on the dialogue with nature’s plants, nature’s springs and the fertile soil.”

Nettleford said he felt Carifesta was meant to reflect this reality or philosophy but it did not mean “chronic disorder.” However, he said, cynics would be quick to find in it reason for periodical displace of political mismanagement and as licence for lawlessness under the guise of freedom and human rights and the incidents of military coups, but there were regulative principles which underlay all of the experiences.

These regulative principles happily give cause to repetition and ritual evident in Caribbean arts and cultural expressions, he said, stating that these in turn give to the peoples of the region a sense of place even when they operate on the margin and find cause to question the principles. The pre-Lenten carnival is but one dominant paradox in the “festival art” in contemporary Caribbean life. “It is used for conventional means of release, recreation and celebration alongside the attraction for tourists whose US dollar or Euro is vital to the Caribbean economic survival in these globalised times,” he said.

He said that many, including himself, believe that the region’s textured diversity was also evident in carnival – pre-Lenten in origin and arguably the most definitive of festival arts nurtured throughout the plantations in the Americas from Havana, Port au France through Port of Spain to Rio De Janeiro, as well as, all of the eastern Caribbean and New Orleans thrown in between.

He said he believed it was the prime socio-cultural practice that best expresses the strategies that the people of the Caribbean have for speaking at once about themselves and with the world, history, tradition, nature and even with God.

Carnival

This he also feels this was the basis for the philosophy of the Caribbean self and to which that Caribbean persona, individual and collective must relate and which Carifestas were meant to mirror.

He said the Caribbean Diaspora was itself a preserve of this cultural phenomenon and so Brooklyn, New York, Boston and Miami, Toronto, Nottinghill in London and Rotterdam have becomes centres of the Caribbean carnival. “Yet in the diaspora, West Indians battle for space and the preservation of a Caribbean identity among migrants who reside in hostile host communities which are struggling to save themselves from contaminants deemed alien to their hallowed homogenous selves.”

Back in the Caribbean, he said, other festival arts exist as part of that same process of self-discovery and the creation of a unifying space that bridges gaps within a society produced by centuries of differentials based on place of origin, skin colour, class, gender and the more modern differentials of political affiliation and sexual orientation.

So there is the more recent crop over festival art drawing on the historical experience of the sugar cane slavery in Barbados, which has revived and developed a time one celebration into a major contemporary calendar event of national observance.

He said ‘Hosay’ serves to bring into the loop of Caribbean cultural life the Indians who entered Caribbean society, after the abolition of slavery, as indentured labourers. He noted that they were fully equipped with a cultural memory of Mohamedism and Hinduism, and the cross-fertilization process continued while the paradoxes of new encounters increased, deepening the already enriched mixture even while tensions played with social and political relations. In Jamaica, the Afro-West Indians often do the drumming while the Indo-West Indians do the dancing. To an extent this applies in Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago.

He said that the Indian spirit in the Jamaican pocomania speaks to the early integration of Asian indentured labour into ex-slaves syncretized religious rituals which are themselves products of cross-fertilization.

Festivals

There are of other festivals, equivalent to the pre-Lenten carnival, which are rooted in the encounter of Africa and Europe and others on foreign soil in the Americas. This includes the Masquerade in the Leeward Islands, Jamaica, Belize and the Bahamas under the name Junkanoo and in Bermuda as ‘gumbay’, as well as in Cuba and Haiti. They all represent the essence of cultural life and the indiscriminate fusion of European musical classical, as well as, instruments of the most varied origins, which produce a new music.

The textured diversity of Caribbean culture, he said, was arguably the most significant clue to understanding the dynamism and energy that characterises life in this region. He noted that it stretches geographically from the Bahamas across the Greater Antilles proceeding for over 1,000 miles southwards along an archipelago comprising the Leeward and Windward Islands with Barbados to the east then south to Trinidad and Tobago and the Netherland Antilles lying north west of Venezuela and Colombia “which they insist is a Caribbean coastline”. The Guianas on the South American mainland regard themselves as Caribbean as would much of north-east Brazil for definitively cultural reasons.

He said the Caribbean features in the great dramas of the Americas where new societies are shaped new sense and sensibilities are honed and appropriate designs for social living are crafted through the cross fertilization of distant elements. This process has resulted in a distinguishable and distinctive entity called Caribbean through an intensely cultural process. This was the result of an encounter of Africa and Europe on foreign soil with the native indigenous Americans and still later, arrivals from India and China and subsequently the Middle East. They have resulted in a culture of texture and diversity held together by a dynamic creativity, described as “creative chaos”, “stable disequilibrium”, or “cultural pluralism.”

Diversity

He said an apt description of the typical Caribbean person was “part African, part European, part Asian, part Native American but totally Caribbean.”

The creative diversity, he said, was what defined Caribbean life, and what the Francophone, Spanish-speaking, Dutch-speaking Caribbean, the British Overseas Territories, the US Caribbean, including Puerto Rico, have in common despite the differences in languages they use and the political systems. They perceive themselves to have in common a full grasp of the power of cultural action affording their inhabitants a sense of place and purpose.

Martinique and Guadeloupe, Curacao and St Maarten, Cuba and Santo Domingo, along with Haiti and Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands as well as the British colonies of the Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands and Montserrat and the Turks and Caicos Islands identify culturally with the independent nations from the Bahamas and Belize to Trinidad and Tobago.

Because of its diversity, he said the Caribbean has the capacity to build bridges not only among classes and races of people from countries across the region but also between continents of the world which are represented in the Caribbean through centuries of voluntary and involuntary migration which is now continued via tourism, commercial transaction, and professional contacts. The Caribbean has struggled for over five centuries with mastering the management of the complexity of such diversity, he posited.