Al Creighton

Anne Walmsley sent a note on May 15 to say, “You, like so many of us, must have been reeling from news of the sad loss of one great Caribbean writer after another: Césaire, Archie Markham, OR Dathorne, Wordsworth McAndrew in quick succession. Now Roy Heath. His eldest son Rohan, rang me to say that his father died yesterday morning.”

It was indeed a bad stretch for Caribbean literature as a whole, considering the importance of some of these writers to one corner or another in the foundations of the literature. Aimé Césaire was foremost in the development of negritude in French Caribbean literature, and the advancement of Postcolonial literature or the literature of resistance, as some prefer to call it. Among those championing that preference was Professor Fred Case of the University of Guyana, an authority on Césaire, who took issue with many of the established critical terms, including Postcolonial and Creole. Unfortunately, Case was added to the grim, quick succession of losses within a month after Césaire.

Archie Markham was among that generation of Caribbean ‘exiles’ who developed West Indian literature in England, while OR Dathorne was a Guyanese writer in the USA. His greatest contribution was the anthology Caribbean Verse, which was a useful historical text, while he was also a novelist with the distinction of being one of the six shortlisted for the first Guyana Prize for Fiction in 1987. Wordsworth McAndrew was a poet, not regarded among the first flight of leading Guyanese poets, but for a long time the country’s most outstanding folklorist. McAndrew is celebrated for his work in researching and broadcasting Guyanese folk traditions while promoting the local short story.

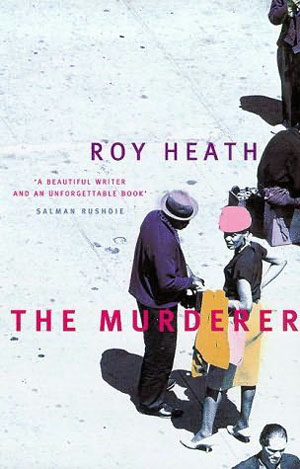

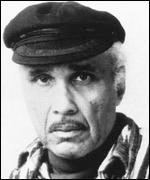

Roy AK Heath (August 13, 1926 – May 14, 2008) was one of the most prominent Guyanese novelists described by Margaret Busby as “a writer of prodigious talent” and “a chronicler nonpareil of 20th-century Guyanese life and lore.” Among his distinctions were the Guyana Prize for Literature for Best Book of Fiction 1989 with The Shadow Bride (1988); the Guardian Fiction Prize for The Murderer (1978), acclaimed as his best work and listed in The Modern Library as one of the “200 Best Novels in English since 1950.”

Roy AK Heath (August 13, 1926 – May 14, 2008) was one of the most prominent Guyanese novelists described by Margaret Busby as “a writer of prodigious talent” and “a chronicler nonpareil of 20th-century Guyanese life and lore.” Among his distinctions were the Guyana Prize for Literature for Best Book of Fiction 1989 with The Shadow Bride (1988); the Guardian Fiction Prize for The Murderer (1978), acclaimed as his best work and listed in The Modern Library as one of the “200 Best Novels in English since 1950.”

About his first book and the beginning of his career as a writer, Margaret Busby writes in the Guardian, May 20, 2008 “A Man Come Home (1974) was championed by the writer Anne Walmsley, after which it was my good fortune to become his editor and publisher at Allison and Busby.” Walmsley, critic of literature and the fine arts, editor of In the Sun’s Eye, author of a seminal work on the Caribbean Artists’ Movement and authority on Guyanese art, tells the story of this “championing,” which Busby included in her Guardian obituary.

“I first met Roy Heath in the early 1970s at the home of the Guyanese painter Aubrey Williams. They shared a particular passion for Guyanese folklore and its myths, which Aubrey was later to picture in a series of paintings, and on which Roy was to research and lecture. The ‘fair-maid’ myth was the inspiration of Roy’s first novel, A Man Come Home.

“Because I was then employed by Longmans as Caribbean publisher, Roy told me about this book, on which he was working. Eventually, he sent me a typescript, its pages tightly packed with typed text. As soon as I started to read it, I felt that sense of excitement, of recognition that here was a real writer. The characters were vivid and rounded, the story compelling, the setting closely observed, meticulously remembered. Descriptive detail and metaphor brought the everyday sights, the sounds, the smells of daily life in Georgetown ‘yard’ society unforgettably alive. Although Longmans was essentially an educational publisher and could publish very little apart from designated school reading, A Man Come Home was given a modest first printing there.

“When Roy then sent me another, and much more substantial, typescript, we urged him to look elsewhere for a firm that could bring his work the acclaim, the wide sales, that it deserved. Who better than the then fledgling Allison and Busby?

“When Roy then sent me another, and much more substantial, typescript, we urged him to look elsewhere for a firm that could bring his work the acclaim, the wide sales, that it deserved. Who better than the then fledgling Allison and Busby?

“Roy and I remained good friends, sharing always our love of Guyana – and of classical music. More recently it has been a joy to meet – at exhibitions of Aubrey Williams – his sons, and to hear of their work in music and in filmmaking. The Guyanese creative connections live on.”

Professor Mark McWatt, poet, fiction writer and critic who won both the Guyana Prize and the Commonwealth Writers Prize, elaborates on Heath’s career in the Routledge Encyclopaedia of Literatures in English (1996). “Born Ray Aubrey Kelvin Heath in Georgetown. British Guiana (now Guyana), he attended Central High School and Queen’s College there. Heath immigrated to London, England, in 1950, when George Lamming and Sam Selvon made the same journey, but he did not become known as a writer until two decades after his more famous fellow exiles. Heath read modern languages at the University of London. Upon graduation he began his long career in London teaching French. Although he studied law and was called to the bar both in England (1964) and in Guyana (1973), he never practised.”

Mc Watt also points out that while “it was Guyana’s achievement of independence in 1966 that aroused in [Heath] the desire to become a writer,” there is a major paradox. “Although [his] fiction has fed richly upon his obsessive and meticulous memories of Georgetown and the coastland, his novels cannot be called celebrations of the place and its people. They seem to reveal instead the failures and shameful inadequacies of individual and community.”

Heath’s other novels are the Armstrong family trilogy – From the Heat of the Day (1979); One Generation (1981); and Genetha (1981); Kwaku or the Man who Could not Keep His Mouth Shut (1982); Orealla (1984); and The Ministry of Hope (1997). He also wrote short stories and drama. He was said to be a believer in Jungian psychology and Busby tells us how he was admired by other writers. “Salman Rushdie called him ‘a beautiful writer,’ and to Edward Blishen he was ‘simply one of the most astonishingly good novelists of our time.’”

Critic Jeff Robinson sees a likeness between one of Heath’s major works and Naipaul’s study of Biswas, laughingly renaming The Shadow Bride ‘A House for Mrs Tulsi’ in reference to Heath’s portrayal of Mrs Singh, the Indian matriarch who is the heroine of that prize-winning novel. But more seriously Robinson recognises what is in McWatt’s words, her struggle against a “denial of power and control” and her “revolt against a culture that requires submissiveness in women.” Heath himself commented that one of his major achievements has been the creation of Mrs Singh. As a non-Indian male he created a convincing Indian woman, managing to possess her mind and details of the feminine psyche.

In the acceptance speech when Heath received the award for that book in December 1989, he spoke about time and exile:

“My preoccupation with time is, I believe, the exile’s way of dealing with the separation from his roots. Is not artistic activity a kind of therapy? After all, in man’s early history Art had a magical significance. Dancing, painting and singing were not simply pleasurable. If the pleasure, then, served the magical function, the magical, therapeutic function still lurks behind what we see as purely pleasurable. I write because I need to write.

“As a boy I enjoyed watching cowboy films, attracted, perhaps by the guns that didn’t need to be reloaded and the impeccable performance of the actors’ horses. As a man I pay the price of consciousness, being no longer content with such innocent pleasures. It is with the guarded excitement of a man that I accept this award, with thanks to the panel for choosing a work which took 20 years to mature.”