Kofi Annan, former United Nations Secretary General, famously remarked a decade ago “You can do a lot with diplomacy but, of course, you can do a lot more with diplomacy backed up by fairness and force.” This aphorism became an axiom in Guyana’s relations with its neighbours 40 years ago. In each of the first five years of statehood, Guyana’s territorial integrity was severely tested. The seizure of Ankoko Island in the Cuyuni River in 1966; the intrusion at Oronoque in the New River in 1967; the publication of Venezuela’s ‘Leoni’ decree purporting to annex part of the Essequibo in 1968; the rebellion in the Rupununi and the incursion in the New River in 1969; and the confrontation at Eteringbang on the Cuyuni River in 1970 were all approached with diplomacy backed up by a credible and capable defence force.

On the diplomatic side at the time of independence in May 1966, the Government of Guyana might have misunderstood completely the nature of the United Kingdom’s historical strategic alliance and underestimated the value of its huge trade and investment links with the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In succeeding months, however, Guyana learnt the hard way how dangerous its unsettled frontier with the ally of the former imperial power could be and how difficult it was to achieve a favourable, permanent settlement to the territorial issue. Deliberately indecisive, Britain bequeathed a sloppy legacy of a contested boundary which remained one of the most intractable security challenges to the new state up to the present time.

On the defence side, it was an expensive burden for a small state like Guyana to acquire and deploy military resources to protect one long border. It was much more so to protect two long borders. But such was the task that had to be done to make the nation safe. About forty years ago in December 1967 and August 1969, two major police and military operations had to be undertaken to defend the New River zone on the border with Suriname.

The regional context

The New River zone is estimated to be about 15,540 km² (6,000 square miles) an area that is much larger than Puerto Rico. It is located in the south-east of the country in the Amuku-Acarai highlands which form the watershed boundary between Guyana and Brazil. The terrain is rugged − a maze of steep-sided slopes, narrow valleys and numerous hills and ridges with heights up to 300m. High temperatures and heavy rainfall sustain dense rainforest with a thick canopy and tangled undergrowth. The zone is drained by several tributaries to the New River which flows in a north-north-east direction into the Corentyne River.

The history of Guyana’s boundary with Suriname is long and complex. Duke Pollard’s The Guyana-Suriname Boundary Dispute in International Law and the Government of Guyana’s two monographs − Guyana-Suriname Boundary and Friendship with Integrity: Guyana-Suriname Relations − published at the height of the crisis in 1968 and 1969, provide an adequate account of the Guyana-Suriname problem which need not be repeated.

Guyana’s position, in brief, has always been that the south-eastern boundary between Guyana and Suriname was determined by international agreement among the governments of Brazil, Great Britain and The Netherlands in 1936. The concrete evidence of that agreement is the tri-junction point at the head of the Kutari River where their three territories touched. Since that time, international maps have been drawn on the basis of that agreed point. In addition, Guyana always exercised sovereignty over the zone by granting licences and concessions to balata-bleeders and wood-cutters. From the colonial era, government geological expeditions have conducted surveys and rangers from the departments of Agriculture and Lands and Mines have patrolled the zone to enforce regulations.

Dutch geopolitics

Much happened to alter the attitude of the Netherlands to Suriname’s mineral resources and its western border between 1936 and 1966, however. Weakened by invasion and occupation during the Second World War, the Netherlands was exhausted further by a costly but unsuccessful colonial war with its subjects in the Dutch East Indies. That second war resulted in the independence of the new state of Indonesia in December 1949 and the loss of many of its lucrative economic interests there. As a result, the Netherlands revived its interest in Suriname, its next largest colony, as a source of strategic raw materials.

Suriname, by the 1950s, had become the world’s largest exporter of bauxite and, unlike all other underdeveloped countries, already possessed a fully integrated industry − from mining bauxite ore to processing alumina and smelting aluminium. This industry would eventually generate 80 per cent by value of all Suriname’s exports. The expansion of production meant tapping new reserves in western Suriname, developing new hydro-electrical power sources and constructing transshipment facilities on the Corentyne River.

Suriname’s quest for new sources of hydroelectric power led it to conduct hydrographic surveys deep within Guyana where it was calculated that the volume of water flowing from the New River was greater than that of the Corentyne River. Largely on that basis, Suriname simply passed a resolution in its Staten thereby inventing a fictional frontier by changing the name of the New River to the Upper Corantyne (Boven Corantijn) and laying claim to it in 1965, the year before Guyana’s independence.

Suriname had been granted internal self-government under the Statute (called the Statuut) for the Kingdom of the Netherlands that established a tri-partite state – comprising the Netherlands, the Netherlands Antilles and Suriname – in 1954. Suriname had its own parliament (called the Staten), a governor and a council of ministers but the Netherlands retained responsibility for defence, foreign affairs, human rights, rule of law, good government and certain other matters. The Royal Netherlands Army created a separate force – Troepenmacht in Suriname (TRIS) – which had responsibility for the security of Suriname but remained under Dutch command. The 1,100 strong TRIS served as a training mission for Surinamese volunteers and conscripts. Troops were stationed at the airport at Coeroeni and other places in the south-west of Suriname as the territorial controversy between Suriname and Guyana worsened. Dutch troops, however, avoided confrontation with both the British and Guyanese.

As Venezuela revived its claims to the Essequibo on the approach of Guyana’s independence, The Netherlands took the opportunity to press the claim that the New River (which it now began to refer to as the Upper Corentyne) was the boundary and all the land to the east of that river belonged to Suriname. When the British garrison departed Guyana in October 1966, Venezuela’s National Armed Forces seized the island of Ankoko in the Cuyuni River and Suriname, similarly, tried to seize the New River.

Suriname’s politics

By the mid-1960s, severe internal political tensions had arisen in Suriname as the shaky coalition administration between the mainly Creole (ie, African) National Party of Suriname (NPS) led by Johan Pengel and the mainly Hindustani (East Indian) United Hindustani Party (VHP) led by Jagernath Lachmon unravelled. Pengel, after the elections of May 1967, formed a new administration but several members broke away to establish a new party thereby weakening the NPS.

At this time, the Suriname government launched Operation Grasshopper, a scheme to establish a network of airfields in the hinterland, including in the New River Zone on Guyana’s territory, which it claimed. Hydropower workers of the Bureau Waterkracht Werken (BWKW) were sent into to the New River but were expelled by the Guyana Police Force in an action called Operation Kingfisher in December 1967. This event provided the opportunity and pretext for a protracted propaganda campaign that permanently poisoned Guyana-Suriname relations.

Premier Pengel delivered an inflammatory broadcast over the SRS radio station on January 3, 1968, deeming Guyana’s military presence in the New River zone “a state of war.” He promised that the surveyors would return to resume their work; that his administration would ensure their safety; and that, “if necessary, armed force shall have to be used.” He declared, further, that “the government has decided to call up volunteers for military service between the ages of 18 and 35 years who have already had military training” and, for good measure, ordered the expulsion of all Guyanese (estimated then to be about 2,000) from Suriname.

As Pengel’s political popularity plummeted and his internal problems multiplied, his resort exaggerating the external controversy with Guyana intensified. The text of the radio broadcast was published as a ‘white paper’; demonstrations of youths were staged in Paramaribo; accusations of treason were hurled at the Netherlands’ press and there were widespread fears that the two countries were heading for a violent military collision. Guyanese overtures for conciliation or negotiation were ignored or rebuffed.

The Dutch dilemma – the urge to restrain the excesses of an intemperate premier without paying the political cost of provoking anti-Dutch sentiment – had to be faced. Two weeks after Pengel’s outburst, the Vice-Premier and Minister of Realm Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands Dr Johannes Bakker made it clear that in no way would Dutch troops become involved in the territorial controversy as “There are sufficient means for settling the dispute peacefully.” With the aim of curbing Suriname’s bellicosity, perhaps, Dr Bakker travelled to Paramaribo to discuss “procedures for negotiations” on the border situation which were drawn up by the cabinet of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The Dutch policy was one of avoiding armed conflict and, in any event, the Kingdom retained firm control over the Troepenmacht in Suriname. That force could not be commanded by the Suriname administration and seems never to have been allowed to enter the New River zone.

Apparently with Vice-Premier Bakker’s agreement, Premier Pengel established a new 200-man force – the Defensie Politie (DEFPOL) – as a branch of the police under Suriname government control. DEFPOL was not a normal law enforcement agency but an armed, uniformed and militarily-trained force that was placed under the command of a Dutch-Javanese Major Lapré, a veteran of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL), which had been demobilised after Indonesia’s independence.

Evert Azimullah in his The Seizure of Camp Tigri claims that the DEFPOL established four camps, the most formidable of which was a jungle fortress located on the eastern bank of the New River. Called Camp Tigri, it was tactically sited on a promontory almost surrounded by rapids. Aided by a bulldozer which had been transported upstream, an airstrip was in the process of being extended to a length of 1,000m with its approaches cleared of vegetation. The camp was well laid out over an area of 1.2 hectares with barracks, bunkers, watchtowers and equipment such as power-saws, electrical generators, refrigerators, water pumps and jeeps.

At first, the DEFPOL seemed to be well funded, commanded and organised. In 1968, it intercepted a Guyana Defence Force river patrol whose engine had broken down. The patrol was seized and taken to the Dutch troops’ (ie, TRIS) camp but they refused to take responsibility for the patrol as they claimed that “they were not at war with Guyana” and the soldiers were released.

But Premier Johan Pengel’s political position continued to deteriorate when radical trade unions organised massive strikes against his administration in January and February 1969. Three of DEFPOL’s four camps had to close owing to financial problems; only Tigri continued to function and Major Lapré the commander was retrenched. Pengel’s administration collapsed in March 1969 and was replaced by an ineffectual, transitional, non-party administration of Premier Arthur May, a former civil servant in the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Elsewhere in the Tripartite Kingdom, fresh troubles broke out. In Willemstad, Curaçao, in the Antilles, arson and rioting erupted in May 1969 necessitating the deployment of Royal Dutch Marines. These events, together with the prospect that Suriname would be granted independence against the wishes of a significant minority, precipitated a flood of unwelcome Surinamese migrants into the Netherlands.

Guyana’s defensive strategy The distraction of the Netherlands government by the Curaçao disturbances; the disarray of the interim administration in Paramaribo; the determination of TRIS to remain aloof from the territorial controversy and the weakening of the DEFPOL in southwestern Suriname were a rare coincidence, the significance of which was not lost in Georgetown. Precisely at this time, Prime Minister Forbes Burnham, who was also Minister of Defence, decided that it was opportune to launch the Guyana Defence Force against the illegal camp at Tigri. Timing was everything.

On the diplomatic side, despite early

efforts at cordiality, Guyana- Suriname relations had been fraught with suspicion. Even before independence, Premier Forbes Burnham had paid an official visit to Paramaribo on January 21-25, 1966 and had met Premier Johan Pengel. But, by June, official negotiations with The Netherlands in London aimed at reaching an agreement on the boundary collapsed and Suriname persisted with its intrusion into Guyanese territory.

Diplomacy having failed, Guyana resorted to other means. After the shocks of the Venezuelan aggression at Ankoko and the Rupununi Rebellion, the Guyana Defence Force was rapidly re-equipped, retrained in jungle warfare and reinforced with additional units.

In the first instance, the administration had launched Operation Kingfisher on Tuesday December 12, 1967. A Guyana Police Force detachment drawn mainly from the Tactical Service Unit and under the command of Superintendent Lloyd Barker was dispatched to the zone to “investigate reports” that Surinamese surveyors had been conducting explorations there. According to the Prime Minister’s deliberately but deceptively bland statement in the National Assembly:

“On Saturday December 9, 1967, it was reported to the Government of Guyana that there were certain Surinam personnel in the triangle between the New River and Oronoque River purporting to be acting for, and on behalf of, the Government of Surinam… On Tuesday December 12, 1967, the Government caused to be ejected from Guyanese territory those persons who had no permission whatsoever from the Government of Guyana…”

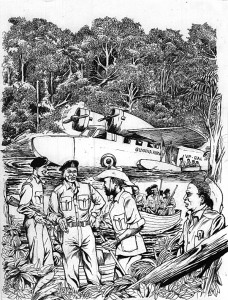

The police detachment was transported in the Guyana Airways Grumman G-21 Goose amphibious aircraft to a landing pool where the BWKW surveyors had their camp near the confluence of the Oronoque and New Rivers, about 90 km from the estuary of the New River. Comically, this necessitated summoning the surveyors to bring their boats to the aircraft to permit the policemen to deplane. The police treated the 40 members of the Surinamese survey party working at Camp Oronoque as ‘illegal immigrants,’ relieved them of their shotguns and expelled them. The police force detachment was later replaced by a defence force platoon.

At the diplomatic level, this incident led to the sharp deterioration in relations between Guyana and Suriname. Guyana consistently made protests against any perceived infringement of its sovereignty or breach of an international agreement or convention but, under the Statuut, it was the Kingdom of the Netherlands that retained responsibility for Suriname’s external affairs. As a result, on Monday, January 15, 1968, less than a month after the Camp Oronoque incident, Guyana’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom Sir Lionel Luckhoo went to The Hague to present his letters of credence to Queen Juliana of the Netherlands as ambassador. As the crisis worsened, Guyana appointed Rudyard Kendall, a former cabinet minister, as Consul General to Suriname in June 1969 in an attempt to improve communication between the two sides and restore cordial relations.

Pengel’s threats were not bluster. Aerial and riverine reconnaissance revealed that the Surinamese had continued to construct a fortified camp (later known as Tigri) on the eastern bank of the New River. The defence force therefore established another camp at Ashiru fall, about 9.6 km from the estuary. The Guyanese and Surinamese forces both maintained camps on opposite sides of the river stalking each other while the politicians did the talking.

After diplomatic negotiation failed, the Guyana Government decided to evict the intruders forcefully. Owing to the rugged terrain, the rough river which was riddled with rapids, and DEFPOL’s commanding position at Tigri, it was considered unwise to conduct an assault against the occupied area either by land or river. The operation to quell the Rupununi Rebellion in January 1969 had proven the invaluable and inevitable role of air transport in hinterland security and this might have influenced the chosen course of action.

The assault on Tigri

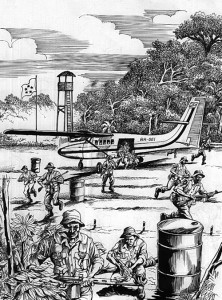

The Chief Pilot of Guyana Airways Roland da Silva was convinced that an assault could be made onto the unfinished airstrip. The corporation’s De Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otter utility aircraft possessed a remarkable Short Take Off and Landing (STOL) capability. Guyanese planning of the operation kept abreast of Surinamese construction of the airstrip until it was cleared to a usable length. DEFPOL elements in the camp, however, blocked the incomplete strip with several 200-litre metal drums.

Colonel Clarence Price by that time had been appointed Chief of Staff of the Guyana Defence Force and the task force selected for the operation comprised troops of the 1st battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Robert Stephenson. Captain Martin Nascimento commanded No. 1 company; Captain Asad Ishoof, No. 2 company; Lieutenant Harry Hinds, the Medium Mortar Platoon and Lieutenant Marcus Munroe, the Reconnaissance Platoon. The aircraft were piloted by captains Roland da Silva, Michael Chan-A-Sue, Philip Jardim and Anthony Mekdeci.

In the three weeks prior to the operation, the ground forces and aviators trained intensely and became completely confident in the Twin Otters’ performance capabilities which were found to exceed both the manufacturers’ specifications and the operators’ expectations. According to Michael Chan-A-Sue’s The Guns of August and Philip Jardim’s Guyana Defends Itself – two first-hand accounts of the operation by the pilots – it was determined that a fully-laden Twin Otter could be brought to a halt within the space of 100 m and that its propellers could clear a 200-L drum standing upright, requiring only that the pilot manoeuvre the aircraft’s undercarriage between the drums to effect a safe landing. The interiors of the aircraft were stripped and the nose compartment of the lead aircraft was modified to carry a Light Machine Gun and a gunner. Warrant Officer Hartley Liverpool was selected as the gunner.

Prime Minister Forbes Burnham gave certain personal assurances to the civilian pilots who had volunteered to participate in the operation and were all immediately commissioned into the defence force as majors. He also visited the concentration area at Tacama in East Berbice where he delivered words of encouragement and personally met every officer and soldier taking part in the operation. The task force was then transported to the Apoteri aerodrome located at the confluence of the Rupununi and Essequibo rivers, about 145 km (90 miles) from the target area. It possessed a relatively good runway, was roomy enough to accommodate a few hundred troops, was remote from observation and its resupply lines were short.

The task force was then ready to launch a lightning assault – called Operation Climax because it was the culmination of years of confrontation by Suriname. It was executed in three phases aimed at driving members of Suriname’s Defensie Politie from Guyanese territory – first, the capture of the airstrip; second, the capture of the camp; and, third, the consolidation of the position. The operation began at dawn on Tuesday, August 19.

In the first phase, each aircraft took off with 22 armed soldiers on board. On landing, the soldiers exited from the open doorway while the aircraft was still on the roll and, as soon as the last soldier was out the door, full power was applied and the aircraft leapt off the remaining length of the airstrip and sped away. Once the airstrip was cleared of obstacles and secure from counter attack, rapid mortar fire was laid. In the second phase, assault troops moved quickly through the jungle towards the target. The Surinamese abandoned the camp, fled to the waterside and were allowed to enter their boats and return to their home country. In the third phase, patrols dominated the surrounding area one of them coming upon the 18-year-old Surinamese Margo van Dams who was apprehended and repatriated. In the space of less than 5 minutes, the two aircraft deposited 45 troops on the airstrip. Refuelling was done and reinforcements were ferried from Apoteri.

Remarkably, the task force took Tigri without bloodshed or casualties. Symbolically, Suriname’s five-star flag was replaced by Guyana’s Golden Arrowhead and the camp was renamed ‘Jaguar,’ the national animal.

Diplomacy and defence

Addressing the National Assembly two days after the operation on Thursday, August 21, Prime Minister Burnham declared how “shocked” his administration was that the Surinamese government had infiltrated armed personnel into Guyanese territory in violation of a mutual understanding arrived at after the Operation Kingfisher incident in December 1967. He reported to the Assembly with faux modesty:

“On the morning of Tuesday, the 19th instant, a detachment of the Guyana Defence Force took over an airstrip and military camp which had been unauthorisedly constructed by Surinamers on Guyana territory in the New River Triangle. A number of Suriname military and civilian personnel occupying the camp, after some armed resistance, fled by boats to Surinam territory leaving behind certain equipment and arms. The action of the Guyana Defence Force was essentially a police action to remove unauthorised aliens from Guyanese territory.”

Within weeks, the peace-making process was greatly facilitated by Prime Minister Eric Williams and the Government of Trinidad and Tobago in brokering two accords. The first was reached at a meeting of Forbes Burnham of Guyana and Jules Sedney of Suriname on April 9-10 at Chaguaramas in Trinidad. An important outcome of the meeting was the proposed demilitarisation of the border area:

“With a view to ensuring peaceful relations between the two countries, the Prime Ministers agreed in principle that there should be an early demilitarisation of the border area of Guyana and Surinam in the region of the Upper Corentyne…”

During Dr Sedney’s visit to Georgetown two months later, a ‘Joint Declaration’ was issued on June 27, 1970, the two sides agreeing to “…the immediate demilitarisation of both countries of their respective presences in the region of the Upper Corentyne…” among other things. The ‘Declaration’ was doomed to remain just that − a non-binding statement which did not have the status of an agreement or even a treaty. Thus, although the Guyana side gave the assurance that it started to withdraw its military personnel between the April and June meetings, there was never any evidence that the Suriname side either ratified the ‘Declaration’ or withdrew its forces.

Although Forbes Burnham paid a reciprocal visit to Paramaribo on November 4-8, 1970, the fractured Guyana-Suriname relations never been repaired and the positive action taken to defend the New River rankled forever it seems. Writing 35 years after the New River incidents, Tyrone Ferguson in his The Guyana-Suriname Conflict: Is the Moment Opportune for Third-Party Intervention? quoted a Surinamese member of the National Assembly as stating reflectively “the pain of Tigri… still sticks in our throats.”

What was a small state to do? Bequeathed a messy imperial legacy of a contested border at the time of independence, Guyana was obliged to expend its own scarce resources in order to create a talented diplomatic service and skilled defence force to protect its patrimony from a predatory neighbour. In the final analysis, the measures the nation took to defend the New River in the 1960s were powerful proof of the validity of Kofi Annan’s maxim about the efficacy of “diplomacy that is backed up by fairness and force.”