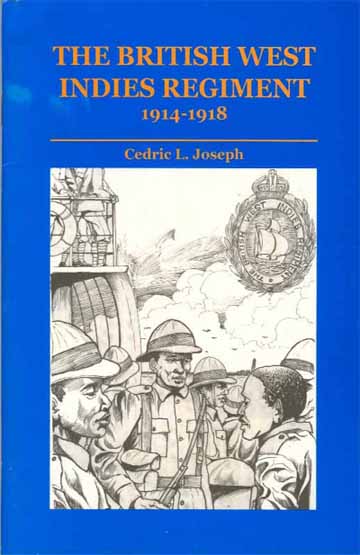

Cedric L Joseph, The British West Indies Regiment, 1914-1918. Georgetown: Free Press, 2008. 46 pp. ISBN 978-976-8178-26-8.

by David A Granger

The West Indies were among the first British colonial possessions in the early 17th century. Even today, nearly four centuries later in the early 21st century, they are the only region on earth where so many British dependencies remain. Despite such strong and historical ties, it might seem paradoxical that people who have been bound to the British Empire for so long would be treated so badly by their mother country.

But this is what Cedric Joseph’s monograph – The British West Indies Regiment, 1914-1918 – is all about. This is not a paean to martial heroism and patriotism by a loyal soldiery; rather, it is a tragic tale of deception and discrimination by an arrogant caste of military officers and colonial officials. Today, it might seem to be the height of stupidity that a small island, desperately seeking manpower to wage another of its wasteful wars, would not welcome ardent volunteers from any quarter. But that is exactly what happened over 90 years ago.

Joseph’s book is a cogently argued account of West Indian participation in the war that combines both chronological and thematic approaches. Starting at the outbreak of war in Europe in August 1914 when there was a great upsurge of patriotism for the Empire among West Indians, it ends a little after the armistice in November 1918 when an attempt was made to besmirch the West Indian record with insinuations of insubordination.

In the beginning, both the Colonial Office and the War Office accepted the argument that black West Indians should not be opposed to white forces. But there was a policy dilemma. On the one hand, the Colonial Office, which had responsibility for administering the colonies, sought a way to recognise and encourage West Indian participation in the mother country’s struggle. On the other hand, the War Office, which had responsibility for fighting the war, sought every possible way to avoid using black troops entirely.

The War Office saw black West Indians only through racial lenses. From the start, contingents from Canada, Australia and New Zealand and, later, South Africa, were accepted for service in Europe. Contingents from India were intended only to serve in Egypt. The War Office made it clear that it would not accept West Indian troops and it eventually did so only after the personal intervention of the king, George V. Even the experienced West India Regiment − an older force which fought for the Empire for over a century − was shunted aside to the periphery and virtually left out of the war.

The establishment of an entirely new force − the British West Indies Regiment − raised the two issues of granting officers’ commissions to persons who were “not of unmixed European blood” and the employment of black West Indian troops. The first issue was resolved by inflicting some ‘partly trained’ British officers with little or no experience of dealing with West Indians on the West Indian Regiment about to take the field. The solution to the second issue was more excruciating. Excluded from the European theatre for racial reasons, the regiment was sent first to Alexandria. But that was not enough. The War Office then dismantled the first four West Indian battalions in Egypt, possibly to prevent their ever being employed as a fighting force.

As the war wore on, the War Office set about raising further units, eventually sending six West Indian battalions to France not to fight but to provide grueling ammunition-carrying and labour services − chiefly handling ammunition at the railheads and carrying it up to the batteries by day and night, digging cable trenches and emplacements for guns, loading and unloading at the docks and constructing light railways.

Despite this policy, the West Indian battalions that remained in Egypt received some specialist training on machine guns and mortars and in signalling and telephoning and, eventually, some took part in raids in which their performance was exemplary. Lance Corporal T. N. Alexander might have been British Guiana’s first recipient of the Military Medal for ‘exceptional coolness and devotion to duty.’ British Guiana’s Captain R. J. Craig, also, was awarded the Military Cross. The fact is that, even after limited combat, West Indians were able to win an impressive collection of awards – the Distinguished Service Order; Military Cross; Military Medal; Distinguished Conduct Medal; Meritorious Service Medal; and numerous Mentions in Dispatches. The roll of casualties told of the sacrifices made: 185 were killed or died of wounds; 1,071 died of sickness, mainly pneumonia; and 697 were wounded.

Disappointment came the month after the war ended, in December 1918, while at Cimino camp in Italy where there were reports of disorder and disaffection among the battalions. It was learnt later that the battalions had refused only to do work − including washing dirty linen and cleaning latrines, some of which belonged to the Italian labour corps − which was of a discriminatory nature and was part of the work of labour battalions. Generally, however, West Indian troops had not been treated as British troops although they were promised such treatment on enlistment. The remarks of Brigadier General Carey Bernard, the South African camp commandant, that he (Bernard) “had no intention of treating West Indians like British troops; that they were only niggers and were better fed and treated than any nigger had a right to expect,” crudely but correctly summed up official attitudes to West Indians during the war.

The sequel to the incident at Cimino camp was the formation, by sergeants of the Regiment at a secret meeting in the sergeants’ mess, of the short-lived Caribbean League for the promotion of closer union among the West Indian Islands after the War. The League dissolved but its legacy might have been manifest in the thrust towards federation and closer unity evinced by the next generation of West Indians.

A stimulating story that reads at times more like a war novel than military history, this book weaves otherwise awkward data − troop strengths; financial levies; regimental postings; military memoranda − into a cogent and absorbing narrative. The British West Indies Regiment, 1914-1918 – is an exciting, if grimly educational, chronicle of events which inexplicably seemed to have evaded critical analysis by other historians.

This is a tale that needed to be told and should be more fully recognised as a theme in Caribbean military history. Joseph’s deconstruction of the atrocious attitudes and official policies towards West Indians is a good starting point for the re-examination of the rest of the century when later West Indian leaders seemed to forget the lessons of regional solidarity that were learnt at such great cost by the soldiers of the British West Indies Regiment.