Lennox J Hernandez

There is little doubt that our historic architecture is distinctive, especially in its expressive use of timber, Architecture’s oldest building material. Fine Architecture in most civilizations developed through a sustained and increasingly sophisticated use of the easily available local material of the area. Guyana, in its pre-independence days developed a fine tradition in timber architecture; a tradition which is now lost with the social appropriation for concrete and steel. Importantly, not only did these buildings show a sophisticated use of the local material, but the designs created showed a greater sensitivity to the local environment and climate than do many buildings of today.

The nineteenth century domestic buildings of George-town are particularly expressive of this sophisticated use of timber and of environmental syncretism (a term used to describe colonial buildings in developing countries being appropriate structures for a new cultural context in a new environment). The local style of domestic architecture developed steadily reaching its zenith in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, designed and built by master craftsmen. As Prof R O Westmaas notes in his seminal “Building Under Our Sun” of 1970:

“Many of these anonymous craftsmen builders had completely mastered the art of achieving composition in scale, massing and harmony and created buildings which were completely functional for their time and which are, even today, undeniably pleasing to the eye.”

We are, however, aware of one such master craftsman builder some of whose creations are still extant. John Bradshaw Sharples (1845-1913) son of a British architect/builder, James Bradshaw Sharples, and an ex-slave woman, was born in 1845 in the colony. John followed his father’s footsteps and became a builder/contractor. In 1880, he started his own business; British Guiana Sawmill and Kingston Steam Woodworking Factory, located in Water Street. His woodworking factory was extensively equipped with machinery allowing for the finest craftsmanship in his work. Venturing into building contracting, John Bradshaw Sharples carried out what has been described as possibly the largest contract of that time, building all the railway stations, bridges, stores and other railway projects from Georgetown to Rosignol. Sharples also designed and built several houses in Georgetown, recognised by the iron-work stairs and balconies, steep gable roofs and carved doors. The creative skill of this son of the soil produced a distinctive style of Domestic Architecture during the late 19th century. An outstanding example of Sharples-designed houses can be seen in Forshaw Street, Queenstown: whilst another, the subject of this article, is in Duke Street, Kingston. Another of Sharples houses is at the corner of Anira & Oronoque Streets, Queenstown. (A search is currently on for other extant Sharples buildings, whilst detailed studies of his known buildings are being done.)

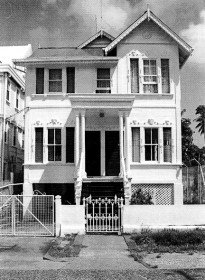

This Sharples house, located on the northern portion of Lot 93 Duke Street, on the western side of the street, was constructed c 1890. Kingston was the first area of settlement of the British in Georgetown and this particular part of the street, north of Barrack Street, boasts a fine ensemble of 19th century historic wooden colonial homes, though some have already been lost. To protect the historicity of this area the best of these buildings, including the Sharples house, should have already been listed on the country’s Register of National Monuments, whilst the entire area should be a Conservation Zone. Since its construction, this Sharples house has had several owners, the current being the Bauxite Industry Co Ltd, from December 1977. Early owners include M A Pereira who bought it in 1908 and C P Gomes who bought it in 1921.

The building is narrow, with a frontage of about 25 ft, it being on one of the few sites in this area that was sub-divided into two lots very long ago. This particular site (93B) is 33.5 ft wide, whilst the southern portion (93A) is 37.0 ft wide. Following the Dutch tradition of the day, the building is elevated against flooding (here the ground floor is about seven feet from ground) whilst the columns and foundations are of masonry (or concrete) and the walls, floors and structure are of timber. The various changes in ownership and the change in use from home to office resulted in several modifications, especially of the interior, but the general form of the building, including the roof form, have remained the same. Externally, there have been changes to the actual window types, but the locations of these windows appear to be the same, and a room was added on the north-western corner, ground floor only. An early photograph (undated) of the northern façade shows Demerara windows on the first floor and tall round-headed windows on the ground floor. For the actual window material, glass louvres have replaced the original timber louvres on all façades. Timber decorations on the main façades are much in evidence, attesting to Sharples and his workers skill in timber craft and to the high level of sophistication in building then reached. For example, the decorative treatment of the high level window in the gable of the main roof and of the surrounding elements – the cornice, the bargeboard, and the gable post.

A distinctive feature of this building is the centrally placed open entrance porch with its classical entablature (horizontal roof beam resting on the columns) with a cornice (the top slightly projecting part of the roof beam) and a combined frieze/architrave (the lower part) with running panels of figures – one female, one animal and one male (left to right). The two sets of relatively slender circular timber columns at the front of the porch are placed in clusters of three – one cluster on either side of the entrance – viewed as pairs from the front and sides. The columns are capped with a capital resembling those of the Victorian times with a representation of the classical acanthus leaves and small volutes; column and capital separated by a heavy astragal (bead). The porch and iron straight-flight stair are completed with iron treads, risers and balustrades featuring decorations of leaves, flowers, volutes and bosses put together with an artistic sense of detailing. Terminating the balustrades at the bottom end of the stair are pedestal-type iron newel posts, intricately decorated. The porch floor, which is supported by two brick barrel vaults, is finished with inlaid mosaic tiles with geometric and other decorative patterns of the period.

This Duke Street example of a Sharples house is the high-point of the refinement of traditional nineteenth century domestic house style in Georgetown, showing in façade treatment at least, a meticulous concern for details. Sharples houses go beyond what Pro Westmaas calls “… the more austere panelled exteriors” of most other older houses in Georgetown. The richness of surface decoration and the detailed attention paid to the entrance of the Duke Street Sharples house are characteristic of buildings that have reached a higher level of sophistication than mere building – it has become Architecture, and this Sharples house can compete with many on the international stage.