The Guyanese public learnt from the BBC in late October of the British Government’s decision to abandon the negotiations with the Guyana Government of Guyana on the ₤ 4.9M Security Sector Reform Action Plan. The administration responded with resignation but without a full explanation of the implications of the British action for day-to-day law enforcement in Guyana.

The need for security sector reform became evident in attempts to suppress the troubles which erupted and escalated on the East Coast in the aftermath of the breakout of the gang of five desperadoes from the Georgetown Prison on 23rd February 2002. The Guyana Police Force was unprepared for the intensity and severity of criminal violence and gang warfare. It was clear that extraordinary solutions had to be found both to the short-term situations created by the crisis and to the long-term maintenance of public safety.

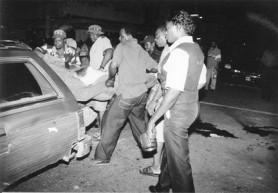

Official responses to the crisis were hardly surprising given the standard of training, the shortage of manpower and the state of resources and equipment in the Police Force at that time. These deficiencies, in the public mind, were aggravated by the reported misconduct of rogue policemen in the Target Special Squad who were blamed for the shooting to death of several suspected criminals. The attitudes of other members of the Tactical Service Unit have also been criticized. Many villagers alleged that young men were detained without warrant; that suspects had been shot down without investigations being held; that their homes had been repeatedly searched and that their property was damaged without compensation. Security operations, as a result, received scant cooperation from the public.

Criminal elements filled the void created by the absence of effective law enforcement. Death squads sprung up and dubious shoot-to-kill tactics were employed against suspects. Although many known criminals were executed in the counter-crime campaign, many policemen − the largest number in the history of the Police Force − were also killed by bandits. Worse still, the surge in criminal violence was augmented most visibly by the growth in narcotics trafficking and the influx of a large quantity of assault rifles and ammunition into the country.

Cooperation

In light of the grave crisis in public safety, President Bharrat Jagdeo promulgated a $100 M, counter-crime plan on 7th June 2002. The menu of measures included a complete review of the existing legislation on crime; comprehensive reform of intelligence-gathering, analysis and dissemination; improving the Criminal Investigation Department’s investigative and forensic capability; establishing a specialised training school where policemen would be exposed to modern methods of anti-crime tactics and creating a ‘crack squad’ along the lines of a special weapons and tactics team.

This plan had little immediate effect on the raging violence although it did much to explain the President’s concept of security reform at that time. The administration also initiated various consultative measures − including establishing the Steering Committee of the National Consultation on Crime, the Border and National Security Committee and the Disciplined Forces Commission − to seek solutions to the unfolding national security crisis.

The administration then approached the British government for security assistance. President Jagdeo visited London in May 2002 and personally met with the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police to seek support for his counter-crime campaign. The following year, 2003, a UK Defence Advisory Team visited the country and produced a report on ways in which the capability of the Police Force could be enhanced. The next year, in October 2004, another Defence Advisory Team visited, as did a group of instructors to train members of the Police Force’s Tactical Service Unit to become the core of a Special Weapons and Tactics strike force. The next year, an eight-member team of officials from the Scottish Police Service and the English Police Service came to study the functioning of the Police Force. A Security Sector Defence Advisory Team visited and issued another report in November.

The president personally met Baroness Valerie Amos in Georgetown in April 2006, soon after the assassination of a government minister, Satyadeow Sawh. Baroness Amos had previously served as Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and as International Development Secretary and the two were able to agree on a Statement of Principles which became the basis for what was to be the final round in the saga of security sector reform. The same year, a team from the Global Facilitation Network for Security Sector Reform came to conduct a study of the Police Force that led to the Security Sector Reform in Guyana report in 2007. A task force from the National Policing Improvement Agency International Academy then visited.

The cumulative effect of all of these initiatives was to show that enough evidence and experience existed to draft, finally, a comprehensive Security Sector Reform in Guyana plan. That proposal included specific support to the reform process in the Police Force over a two year period, 2006-2008.

Implementation

Security cooperation between Guyana and Britain never ceased during this period. The International Policing Adviser for Latin America and the Caribbean spearheaded a task force from the National Policing Improvement Agency International Academy at Bramshill and the Scottish Police College to begin to implement the Security Sector Reform Action Plan. The international department of the Scottish Police College, which provides learning and development opportunities in operational policing, police leadership and performance management and Centrex − the trading name of the Central Police Training and Development Authority which was subsumed within the new National Policing Improvement Agency − have been involved with local police problems and programmes for a long time.

The Scottish Police College, in particular, has executed several projects since 2004. Starting with a scoping exercise to assess the Police Force’s training requirements in December 2004, it then conducted a series of management training programmes in February-June 2005; an assessment of the impact of the previously delivered training programmes in December 2005; and another scoping exercise in May 2006. Those were followed in June 2006 by the presentation of the Guyana Police Force Strategic Plan in partnership with the Inter-American Development Bank as part of the Guyana Citizens Security Programme. It also executed a project to assess the police force’s operational capability in October 2007.

British consultants from the Police Service of Northern Ireland also continued to work with the Police Force to help develop crime intelligence, advise on structures, provide training and conduct a needs analysis for the setting-up of the new, expanded Criminal Intelligence Unit, in March 2008 under the Interim Memorandum of Understanding.

It seemed evident that the type of organisation and level of administration required to support the reform process might have been underestimated. In fact, even before the troubles on the East Coast had erupted, and in response to the Guyana Government’s specific request in 2000, the United Kingdom Department for International Development had commissioned a strategic review of the Guyana Police Force which produced the comprehensive Guyana Police Reform Programme, conducted by the Symonds Group Limited.

Known locally as the Symonds’ Report, it was aimed at helping the force’s senior management to determine the functions of an accountable, professional force; developing a community-based policing style; and helping the government to identify the areas to strengthen performance, accountability and community orientation of the Force. The establishment of a witness protection programme and better management of information, particularly with regard to fighting narco-trafficking, were also recommended.

For most of the past seven years, the Guyana Government has been receiving British Government assistance to reform the security sector and to support the improvement of the Police Force’s capability. The efficiency of the British public safety establishments which have been so frequently involved in advising and training the Police Force has not been disputed. But it was always up to the Guyana Government to implement the policy recommendations which have been made.

No one should pretend that the administration and the Police Force itself were not affected by capability constraints and little was achieved in implementing these weighty recommendations in a holistic manner. The Police Force itself did establish a ‘Task Force on Organisation Change’ but this collapsed because of inadequate funding and full-time staffing. It was not until January 2009 that the Security Sector Reform Secretariat was established within the Office of the President as a permanent institution to continuously manage change in the security sector.

Concept

It became clear, as time went by, that the practice of sending groups of experts to study Guyana’s security sector problems and to make recommendations was not contributing sufficiently to improving public safety. But then there was a change in both the concept and content of proposed security sector reform. Assistance from donor countries was required to conform to current international practice as prescribed by guidelines promulgated by the Paris-based Organi-sation for Economic Cooperation and Development to which the United Kingdom subscribes.

The OECD’s Development Assistance Committee defined security sector reform as seeking to increase a country’s ability to meet the range of security needs within society “in a manner consistent with democratic norms and sound principles of governance, transparency and the rule of law [that] includes, but extends well beyond, the narrower focus of more traditional security assistance on defence, intelligence and policing.”

Britain’s agreement with Guyana, therefore, should be seen in the context of this concept. It is not the result of a stand-alone bilateral agreement but, rather, a prescription based on established guiding principles, tailored to national needs but in accord with international security norms. The Security Sector Reform Action Plan has been determined by the key policy and operational commitments derived from the Implementation Framework for Security Sector Reform that was agreed on 4th April 2007.

Adherence to the Implemen-tation Framework ensures that the UK’s support for security sector reform programmes is effective and sustainable. It should be quite obvious that, in order to achieve both effectiveness and sustainability, “local ownership” by the Government of Guyana is essential. Accordingly, the Framework states, “The bottom line is that reforms that are not shaped and driven by local actors are unlikely to be implemented properly and sustained.” This, indeed, might have been the problem with earlier efforts prior to 2007 which petered out once the experts departed. Hence, the recent concern has been to improve Guyana Government capability, develop a national security policy and build accountability and oversight.

Under this new OECD-driven Framework, there had been a deliberate moving away from ad hoc, short-term projects to longer-term, strategic engagements; an appreciation of the need to support partner countries in leading the reform process and the adoption of a multi-layered, multi-stakeholder approach which can target assistance to state and non-state actors. The Framework requires donors to aim at the improvement of basic security and justice delivery, the establishment of effective governance, oversight and accountability system and the development of local leadership and ownership of a reform process to review the capacity and technical needs of the security system.

Coordination

It has been apparent, at least for the past couple of years, that security sector reform assistance would be available only in accordance with this overarching strategic concept. The Guyana Government understands the paradigmatic change and this explains why it established an oversight committee for the security sector in the National Assembly; appointed Major General (Ret) Michael Atherly as Project Coordinator for Security Sector Reform and established the Security Sector Reform Secretariat.

The parliamentary committee established to review the implementation of the Plan was required to receive and examine official annual reports from the administration on the status of the implementation of the activities in eleven priority areas on an annual basis and also to provide a final report of its examination of the reports on the implementation of the entire Plan to the National Assembly. These measures were components of the Plan and did emphasise the importance of Guyanese “ownership” of the reform process.

The four-year, ₤3M, bilateral Interim Memorandum of Understanding for a Security Sector Reform Action Plan that was signed by British High Commissioner to Guyana Fraser Wheeler and Head of the Presidential Secretariat Dr. Roger Luncheon on 10th August 2007 was intended to integrate the initiatives of several years worth of reports, recommendations training courses and visits.

The Plan, in the main, provided for building the operational capacity of the Police Force, from the provision of a uniformed response to serious crime, forensics, crime intelligence and traffic policing; strengthening policy-making across the security sector to make it more transparent, effective and better co-ordinated; mainstreaming financial management in the security sector into public sector financial management reform; creating substantial parliamentary and other oversight of the security sector and building greater public participation and inclusiveness in security sector issues.

The Plan was designed also to complement the ongoing Citizen Security and Justice Reform programmes, in an effort to tackle crime and security in a holistic manner and in accord with the OECD’s Framework.

Despite the substantial body of Guyana-Britain security sector reform cooperation over the years, controversy arose in late May over the modalities for advancement of the Plan. An extreme interpretation of the event appeared in an article in the Weekend Mirror newspaper, published on 3rd June, which stated “After 43 years of independence, the British are still trying their best to have their way in the management of the Guyanese affairs” and cited the controversy between the Office of the President and the British High Commission over the security sector reform project as an example.

Controversy

The controversy, in fact, arose out of the negotiations to upgrade the interim memorandum to a permanent agreement as the Framework for the Formulation and Implementation of a National Security Policy and Strategy.” According to Dr. Roger Luncheon − Head of the Presidential Secretariat and Secretary to the Guyana Defence Board and who had governmental responsibility for the project − the framework for the “Formulation and Implemen-tation of a National Security Policy and Strategy” was concluded last year. But in his view, the version of the Security Sector Reform in Guyana Plan which was approved by the British government in April contained a proposal for a four-tiered British management structure which handed the British side “complete control” of the management of the programme.

Luncheon said that such a proposal was “offensive” and would not be tolerated by the Govern-ment of Guyana. The British, he thought, were attempting to convince Guyana that it was suffering from a “capacity constraint” in project implementation, a notion with which the government disagreed totally. He asserted that “Guyanese ownership” of the Plan will be maintained and that the government “will not relent one bit on this.” He added that the implementation of the reforms would indeed be facilitated by the British involvement, but that he is “not going to give up one our dignity [and] our sovereignty for the contribution that could come from this engagement”.

British High Commissioner Fraser Wheeler, on the other hand, reiterated that the British government was committed to Guyanese “ownership” of the process which was designed to be in accord with the OECD paradigm for security assistance. Expectedly, though, local discussions in Guyana between the High Commission and the Office of the President were subject to approval by the UK government which was committed to financing the Plan and this might have been the source of some misunderstanding. He stated plainly that he was dissatisfied with the delay in implementing the reform plan, accusing “some persons” in the administration of “quibbling about administrative details.”

The comments of both the Head of the Presidential Secretariat and the High Commissioner immediately made headline news in late May. Despite the media frenzy, however, moderate counsel seem-ed to prevail by mid-June. Writing in the Weekend Mirror newspaper, Speaker of the National Assembly Ralph Ramkarran referred to the controversy and complained that it was “painful to see relations between the British and Guyana Governments, underlined by unusually strong language, take a negative turn.” Ramkarran’s optimism, however, seems to have been misplaced and the Plan is now dead in the water.

Any objective evaluation of the efforts to reform the security sector over the past seven years would indicate that much ground had been covered; Guyana has been the beneficiary without its sovereignty being compromised. Equally, any review of the public safety situation in the country at present would show how much more still needs to be done.

After the collapse of the British-funded Plan, Dr Luncheon promised that “Security Sector Reform will continue in Guyana, maybe at a different pace and the scope and the design will be different, but the implementation of that will be from public funds from the Government of Guyana.” We shall wait and see what happens.