Part 1

Problems of measurement

For my remaining columns commemorating the Third World Debt Crisis (TWDC) I shall focus the discussion on Guyana’s public debt situation since 2006. Despite its appearance, this decision is not based primarily on the consideration that this covers a convenient recent period for discussion. Instead it is due principally to the fact (which I have drawn attention to on several previous occasions in these columns) that analyses of Guyana’s macroeconomic performance will fall into grave error if the GDP measures prior to 2006 are used in the same time series analysis with GDP values after 2006.

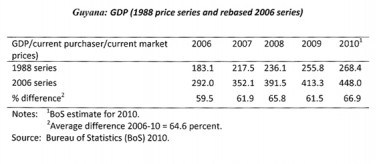

To explain: As I have indicated earlier, debt burden is measured by the total public debt divided by GDP. This yields the familiar public debt-to-GDP ratio. For Guyana, continuity in the measurement of debt burden becomes impossible before and after 2006 because the GDP estimates were rebased in 2006. Indeed the effect of that rebasing exercise has been a substantial increase (about two-thirds) in the size of the 2006 price series GDP estimates when compared to those based on the 1988 price series.

The table below has been provided by the Bureau of Statistics (2010), which has been responsible for providing the rebased GDP measures.

The table below has been provided by the Bureau of Statistics (2010), which has been responsible for providing the rebased GDP measures.

That table displays both the Bureau’s estimates of Guyana’s GDP based on the 1988 price series and the rebased 2006 price series for the period 2006-2010. There it can be clearly seen that the 2006 price series data are on average 65 per cent larger than the 1988 price series GDP measures.

Readers who have been following my Sunday Stabroek columns would have been reminded on several earlier occasions of this situation. It would be useful nonetheless, to repeat once more the statement made by the Bureau of Statistics in the publication cited above:

“A rebasing exercise immediately results in two predictable outcomes: the size of the nominal GDP expands significantly and the growth rate generally increases” (Bureau of Statistics, 2010, page 29).

One other important piece of information needed for this public indebtedness review is to inform readers that I utilize in this review only public debt information accessed from publicly available official sources, mainly the Bank of Guyana and the Annual National Budgets. I have made no independent effort whatsoever to verify these data, as I do not have access to the information required for such an exercise.

For purposes of illustration

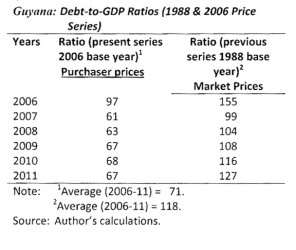

For purposes of illustration only, the impact of the GDP rebasing exercise on measuring the public debt burden (public debt-to-GDP ratio) is presented in the table below utilizing the identical official public debt data sources and the different price series GDP data for 1988 and 2006.

This table reveals the dramatic impact of the rebasing exercise on the main measure of the debt burden, namely the public debt-to-GDP ratio. As can be seen the difference between the average debt-to-GDP ratio based on 1988 prices (118 per cent) and that based on 2006 prices (71 per cent) is quite large, 47 per cent. Of significance, the ratio would have been at 99 per cent or greater for all of the period 2006 to 2011, although it has indeed fallen from a peak of 155 per cent in 2006.

The main lesson

Last week I gave a brief glimpse of what I have termed as “the worst of times” when describing the horribly painful experiences of structural adjustment this country has had to endure in reducing a public debt-to-GDP ratio in excess of 600 per cent to a level of about 200 per cent.

This adjustment was very savage, based as it was almost exclusively on the contraction of the incomes, wealth and living standards of the broad masses of Guyanese people. Today that structural adjustment experience remains a tortured legacy of our post-independence politics.

For our economic legacy, however, it points to one very fundamental lesson. That is, our country is too small, too open, and too poor, to sustain the ravages of significant macroeconomic dislocations. As a result, I urge both the authorities and the parliamentary opposition (who should be over-sighting economic governance in the country) to pay very close attention to the emergence of macroeconomic disequilibria. The speed and rapidity with which these can proceed in dragging the country to a halt and into a vicious downward spiral should never be underestimated.