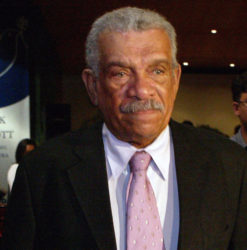

By the setting of the final decade of the twentieth century, Derek Walcott (January 23, 1930 – March 17, 2017) had advanced to be regarded as the world’s best poet. He was the Caribbean’s greatest poet-playwright. He came to be called many things: the Homer of the West Indies, its most exceptional dramatist, a universal humanist. We are witnessing not the end of just another life, not of a man, but the end of an era, of a whole age in West Indian and world literature.

Sir Derek Walcott was knighted as the final crown, the power and the glory of a career that started as early as 1948, and whose conquests along the way included the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1992 and literary prizes, almost fittingly, for his last book of poetry, White Egrets (2010).

Walcott had many other honours bestowed upon him for his elevation and decoration of West Indian poetry, drama and letters, including an Honorary Doctor of Letters from the University of the West Indies (UWI) Mona campus in 1973 – quite fittingly, since that was his alma mater, the place where he literally launched his dramatic preoccupations.

This laureate, this ex oriens occidente lux (light shining out of the west) waxed to become the illumination of learning the university saw itself as. He was born on January 23, 1930, in Castries, St. Lucia, along with his twin brother Roderick, who, interestingly, was also an accomplished playwright. Their parents, Warwick and Alix, were mixed race school teachers. Roddie Walcott produced some of St Lucia’s best known, but mostly one-act, plays, including Malfinis (his best), Shrove Tuesday March, The Trouble With Albino Joe, The Harrowing of Benjy and The Banjo Man (full length).

Of equal interest is that Derek started off in art as a teenager, setting down his first milestones at 18 not as a writer but as a painter, which was his ambition. He first came to wide public attention through a joint exhibition with his friend Dunstan St Omer, reviewed by Harold Simmons, distinguished man of the arts in St Lucia, a mentor who introduced Walcott and St Omer to public and critical attention. But it was St Omer, not Walcott, who went on to be the island’s greatest painter. Walcott, however published his first collection of poems – Twenty Five Poems in 1948 and wrote a one act play – Epitaph for the Young.

From there, as the cliché goes, he never looked back on the road to making one of the greatest contributions to the rise of West Indian literature. But it was not as the cliché would have it – his eventual success was owed as much to perseverance as to genius, according to Edward Baugh, the greatest authority on Walcott’s work. By 1970 Walcott had outstripped many other promising poets of that time because of his steadfast commitment to the craft. That he was not always buoyant and prosperous throughout his long voyage was documented by another biographer, the critic Bruce King. His relationship with the Trinidad Theatre Workshop grew stormy, erupting in an explosive blow-up in 1978, leaving his domestic life in ruins. There have been too many other very outstanding Caribbean writers during the period to say it was dominated by Walcott, but he was certainly a most powerful presence and among the most consistently influential in the making and shaping of the literature, which he took with him to be rated as the finest in the world.

The Jamaica years

Walcott went to the University College of the West Indies (UCWI) at Mona in Jamaica in 1950 to read for a degree. During that period, he seriously launched his career in drama and the time on campus, 1950 to 1954 properly set his foundation. This led straight into 1954-1957 when he wrote many plays (mainly one-act) exploring themes, subjects and formal preoccupations that were to serve him well in later years. Much of what he did in this early phase was to work as experiments for things that concerned him and that he revised and expanded in later plays.

Works such as Henri Christophe, Wine of the Country, The Sea at Dauphin, and Malcochon found themselves revisited in more ambitious drama on the same pursuits. These included full-length plays Franklin, Drums and Colours (1960) and Ti Jean and His Brothers (1958). Walcott had embarked on a search for heroes, heroic studies of the St Lucian peasantry, the folk and mythology. At the same time he began to develop a tragic sense that pervaded this study of the folk.

The Sea At Dauphin is an example that drew on the Irish tragedy Riders to the Sea by Sean O’Casey where Walcott explored similarities between the West Indian islands and Ireland. There were similar comparisons with the Japanese countryside in the tragic, heroic post-colonial study of village peasants in Malcochon. There were two sides of his search for heroes. He looked into the folk heroes of St Lucian mythology in Ti Jean and His Brothers and to heroes of Caribbean history in Haiti, a place acknowledged by the playwright as the producer of heroes such as Toussaint L’Ouverture. This carried over into his epic drama Drums and Colours commissioned for the opening of the parliament of the West Indian Federation (1958-1962) in Trinidad in 1960.

His interest in mythology was not only local, since he started a lifelong preoccupation with the Classics in the way he tried to retell a story of St Lucian peasants by adapting Greek mythology from Homer’s The Illiad in the tragic play Ione. This experiment was to lead to some of Walcott’s greatest achievements such as the long poem Omeros (1990), the play The Odyssey (1992) and even the long autobiographical poem Another Life (1969).

Haiti would have appealed to Walcott, much as it did to C L R James, because of his interest in heroes and heroism, but just as much for the strong post-colonial resonance in its history and in its revolution. Equally, there is its appeal for dramatic study because of its very tragic circumstances. Walcott’s many revisits to Haiti arose from these and culminated in his major play on those themes, Haytian Earth, which irked and offended members of the Trinidadian left wing during performances in 2003 at UWI, St Augustine for the 200th anniversary of the Haitian Revolution, largely because of his unsympathetic treatment of Jean Jacques Dessalines.

Walcott’s ‘Jamaica Years,’ critically examined by Sam Osein, was a very important foundation period for the writer, more than anything else, for his theatre. Most of what he did there, set off crucial preoccupations that directed the way his career moved in the decades that followed. At that time he had introduced a new depth to the Caribbean theatre’s treatment of the society. The prevailing forms were the backyard theatre tradition and its descendants, and a number of one-act comedies collected by Errol Hill for the UCWI Extra Mural publications.

Trinidad 1959 – 1978

Walcott settled down in Trinidad for a much longer period working as a newspaper writer at The Guardian (“a hack’s tired prose”) and was more rooted there than his time spent in Jamaica. His work was immersed in Trinidadian literature while he set down roots in the theatre. It was during this time that his first major collection of poetry appeared – In A Green Night (1962) and he began to develop as a major poet. The mixed reviews accused him of echoing the influence of too many other English poets. The great irony is that the book truly set Walcott on course to greatness. It was a book with a vow sworn on the Bible – “as John to Patmos” by the poet to praise the beauty of the West Indies; to give it a place in the eyes of the world; to “free” the inhabitants from “homeless ditties” by creating verses they could call their own. Not only that, but to learn as a poet to “suffer in accurate iambics”, to find a style that empowered and identified.

I seek

As climate seeks its style, to write

Verse crisp as sand, clear as sunlight,

Cold as the curled wave, ordinary

As a tumbler of island water.

These were promises that the poet kept. He hardened his verse, and helped to give the Caribbean identity in its poetry. The books that followed included Another Life in which Walcott articulated much that informed his writing. He turned what he described as a colonial condition into a blueprint for creative engagement and the imagination. A thoroughly British education led to imitation as he “saw autumn in a rusted leaf,” but taught him Greek mythology that he used to infinite advantage in creativity.

That was one artistic stance adopted by the poet that served him as a sustained metaphor. Another was the thorough identification of himself with the nations of the Caribbean. For example his ethnic mix of black Africa and white Europe – “divided to the vein”, which he used as a description of the Caribbean and its post-colonial condition. It emerged in drama as well as poetry – Dream On Monkey Mountain (1970), Pantomime (1978) and poetic collections The Starapple Kingdom and The Fortunate Traveller. His persona Shabine, captain of the schooner named “Flight”, a mulatto called “Shabine” in French Creole Patois, who declares “I know these islands like the black of my hand.” He famously declares “either I’m nobody or I’m a nation.” Shabine is Walcott himself recommitting to the West Indies.

One of the most important developments of Walcott’s career in Trinidad was in the theatre. His greatest contribution was the founding and development of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop in 1959. His work with this professional company, paralleled in the Caribbean only by Rex Nettleford’s National Dance Theatre Company in Jamaica. Most of the major plays were produced in and for this company, including his reinforced Ti Jean and His Brothers, Dream On Monkey Mountain, The Joker of Seville, Pantomime, The Last Carnival and A Branch of the Blue Nile which was actually about the company and released after he acrimoniously parted company with them. The Last Carnival, too, was post-Trinidad, but it was a reworking of the original version titled In A Fine Castle (1971).

The East Indian question

A criticism of Walcott has been that while his work has thrived on the black/white conflict, post-colonialism and even the concerns of the white French Creole class in Trinidad society, he failed to treat the ever important East Indian presence in the Caribbean, which is surprising given his long residence in multi-ethnic Trinidad. Walcott was ever aware of the Trinidadian socio-political demographics, but his consciousness has always been strongly St Lucian. Yet he did not forget the East Indian presence, and surprisingly, he treats it quite strongly in a St Lucian play.

The reworked version of Franklyn (most recently produced in Barbados by Michael Gilkes), has an Indian heroine who departed from her family tradition. A vivid element in the play is the response of her father who curses and denounces her, ending his interview of rebuke by presenting her with a small vial of poison, which she drinks by the end of the play.

And he did remember to address Indian cultural issues in Trinidad. Such instances are rare, but a good example is the poem – the dramatic monologue “The Sadhu of Couva” in which an old man steeped in tradition and religion laments the waning of belief, understanding and respect for Hinduism in contemporary Trinidad. Another example is in the play Beef, No Chicken, which is however, a farce. He gives humorous, satirical treatment to the kind of shallowness with which some aspects of culture borrowed and sometimes mimicked from India are treated in contemporary Trinidad.

However, Walcott’s most powerful statement on this subject was reserved for his Nobel Lecture delivered in Stockholm before the Swedish Academy when he accepted the Nobel Prize. Unlike the lament of the Sadhu, it is centred on belief. Walcott described the Ram-Lila performance that he saw in Felicity a village in Chaguanas, Central Trinidad, making the point that, for the participants, it was far more than theatre, it was belief. He marvelled at the high level of production done by village people and peasants performing a play that taught the principles of the Hindu religion.

The Homer of the Caribbean

After Trinidad, Walcott had a long career as a lecturer at the University of Boston, USA (1981-2007), but interspersed by extensive travel, phenomenal writings and some controversy. During that time he also re-established in St Lucia where he eventually re-settled. He developed close friendships with Russian poet Joseph Brodsky and the British poet Seamus Heaney of Northern Ireland, to form a trio of the world’s best poets, all Nobel Prize winners. This period of extensive travel surely influenced another of his most outstanding works of poetry The Prodigal (2004), praised by Edward Baugh for the maturity and ‘Caribbeanness’ of its language. Baugh, the foremost Walcott scholar, also edited the most recent collections of Walcott’s poetry, an anthology personally authorised by the poet.

These Homeric travels also took the poet-dramatist to his zenith. The 300 page poem of Homeric epic proportions Omeros (1990) convinced the Swedish Academy in his favour in 1992, but that cannot even be regarded as the very peak of his writing career, considering the volumes that came afterwards. Walcott was quite conscious of his Homeric reputation (it was his ambition) since “Omeros” is Greek for Homer. He compared the Greek coastal islands, their closeness to the sea and history of the sea to the West Indian islands, not least of all St Lucia, the setting of the epic poem where Homer’s Illiad is translated into a conflict between humble working men and Caribbean history. He had already tried this out in the play Ione (1957).

Homer’s other epic, The Odyssey, was adapted for the stage by Walcott, commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC). This was the second time Walcott was engaged by the RSC, which found it impossible to perform the results of its first commission – The Joker of Seville (1974), one of the author’s truly great plays. The poet transformed the Don Juan story into a Caribbean post-colonial adventure with Caribbean rhythms, flavour and theatre which must have been too daunting for the RSC. However, by the time of The Odyssey, the RSC was warmer to the task and performed it to perfection. That was significant since Walcott’s stage adaptation is nearly as Caribbean as Joker. The RSC had successful sold out hits with it in Stratford and at the Barbican in London in 1993.

Walcott’s poetry after the Nobel also included the very elegiac The Bounty (1997), Tiepolo’s Hound (2000), The Prodigal and White Egrets, in addition to the collection edited by Baugh. His drama includes Moon-Child (2011) an extremely poetic revisit of the Ti Jean theatre and theme.

Art

Never having discarded his early ambition, Walcott continued to dabble as a water colourist, before also venturing into oil. It is a moot point as to how much interest would have been taken of his paintings were he not a master writer. There has been fairly little really serious critical attention to them. But his art work is of some merit and gains from the fact that his drawings and paintings have long been companions to his writings. Plays have been illustrated, sketches have been used to enhance, clarify and even influence drama.

Documents in files in Castries show exploratory sketches of the Japanese countryside with bamboos akin to the Caribbean and used in Malcochon. There have been serious exhibitions of his art work, including one in his honour at the UWI in St Augustine. These reveal a preoccupation with landscape, with the sea and sometimes the folk. He was a realist.

Walcott also had a mixed association with Carifesta, which he declared in 1990 to be an excessive waste of money, since it was a grand fete which did not develop the artists and left them in poverty at home (Stabroek News interview). At the same time he lambasted Caribbean governments for their “betrayal of art” and artists. Yet he had famous episodes of participation in Carifesta. For example, his play about Rastafari, Oh Babylon, played at Carifesta in Jamaica 1976, and he was feature speaker in Guyana in 2008 when he challenged then president Bharrat Jagdeo to put money into the arts.

His prose writings have gone the spectrum from newspaper work for Public Opinion in Jamaica and the Trinidad Guardian to deep critical writings in theatre, literature and language. Among the best known, “What the Twilight Said” was mainly about his long endeavour with the Trinidad Theatre Workshop. His preoccupations with the sea and with history are reflected in “The Muse of History” and “The Sea Is History”. He marvelled at the folk theatre of the street when Flavier the White Devil called Papa Djab used to perform at Christmas in Castries. He took on the debate about the English language in the Caribbean, rejecting the quarrel with it as colonial imposition, instead valuing it, as George Lamming does, as “a West Indian language” with great gains for himself as a writer.

Critical attention to Walcott is too voluminous and varied for any attempt here at coverage, however brief. Baugh first focused Walcott’s own essays in Critics on Caribbean Literature (1978), after having published his research in Derek Walcott, Another Life: Memory As Vision (1976). These were followed by Derek Walcott (2006). Another scholar on Caribbean literature, Stewart Brown pulled together much of the disparate works about Walcott when he edited The Art of Derek Walcott (1992). Bruce King’s two large volumes provide extensive history – the personal and the professional in Derek Walcott and West Indian Drama (1995), and Derek Walcott A Caribbean Life (2000).