The essence of Paul Harris’ consummate skill as a cartoonist derives from his appreciation of the unique role of the cartoon as a vehicle for communication. Over time, he has cultivated an incremental understanding of the latitude of the cartoonist’s license, the facility which the medium offers for pushing the envelope of free public expression – further, perhaps, than any other popular communication tool can without encountering the quagmire of litigation.

The essence of Paul Harris’ consummate skill as a cartoonist derives from his appreciation of the unique role of the cartoon as a vehicle for communication. Over time, he has cultivated an incremental understanding of the latitude of the cartoonist’s license, the facility which the medium offers for pushing the envelope of free public expression – further, perhaps, than any other popular communication tool can without encountering the quagmire of litigation.

If the cartoon is not entirely beyond the reach of litigation, it functions in far ampler space than the written word, posing a more formidable challenge to censorial scrutiny and in the process rolling back the limits of media freedom.

There are occasions, Paul says, when his own cartoons have walked the fine line, skirted the edges of free expression. Those experiences have taught him valuable professional lessons. Even the cartoonist’s greater freedom has its boundaries and carries with it a corresponding responsibility.

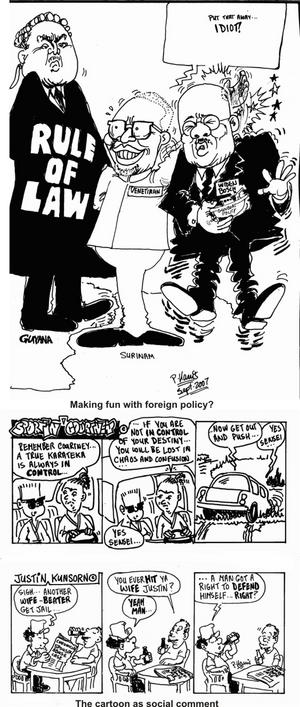

If Paul is realistic enough not to pretend that boundaries do not exist, he concedes that he relishes the challenge of testing those boundaries. His appetite for boundary riding is manifested in his contributions to the Stabroek News that have captured a range of socially and politically sensitive themes, cloaking them in an artistic style that evokes humour without compromising the essence of the comment that he seeks to make.

Harris’s work has assumed a poignant relevance in a society where media freedom has long been the subject of animated social and political discourse and where the re-emergence of privately-owned media houses has coincided with an aggressive assertion of the right to the freest possible public expression.

Cartooning, Paul believes, affords the media a generous window for speaking its mind; for mirroring societal issues; for graphic statement; for “poking fun,” lampooning public figures who would rather be taken seriously. These, he believes are forms of communication that are characteristic of democratic societies and which, moreover, are popular with a broad swathe of consumers of information.

Paul never really set out to be a cartoonist. His ambition, he says, was to become a Civil Engineer. Then he thought that he could become a professional footballer. As a boy he represented Lodge Rovers at the Under 16 and Under 19 levels and he was actually good enough to be part of the Georgetown team that was victorious at the 1977 Inter-Ward championships.

Ultimately, it was the influence of a home environment that thrived on the art of creating visual images that directed his career path. Paul’s father Hawley Harris’s celebrated career as a cartoonist left an imprint on his entire family. “All of us could sketch a fairly decent image,” he says.

As a teenager at South Georgetown Secondary school he was popular for his artistic images………situational comments and likenesses of well-known personalities, public and political figures, fashioned with what he describes as a “weird sense of humour” that often produced amusing disfigurements – huge heads, distended stomachs, oversized noses that could transform appearances in a manner that evoked hilarious laughter. “The cartoonist,” Paul says, “can use the tool of caricature to make people over in his own image and likeness.”

The facility for humorous disfigurement has endured in Paul’s contemporary work. No public figure evades his creative imagination, his discerning eye detecting and embellishing prominent physical features …………. so that a slightly distended stomach becomes a ‘pot belly’ and a prominent nose is perceived as a huge protruding lump. “I don’t mind admitting that I enjoy the facility of lampooning public figures. That side of my work gives a comical edge to what, otherwise, are invariably serious subjects.”

Paul’s first “paying job” was a commission by his father to produce a cartoon for the Guyana Chronicle. He remembers that it went well. He remembers too his own transition from simply fashioning images on paper to infusing those images “with some kind of social meaning.” Justin Kunsorn – a matter-of-fact midget sporting a prominent cap and a permanent cigarette butt on the end of his lip was created during what Paul describes as “the difficult days” of high unemployment, and shortages and no foreign exchange. The character, Paul said, was a visual symbol of what he felt was a desired response to the tough times facing the country at that time. “I suppose the point that Justin was seeking to make was that people shouldn’t worry, they shouldn’t allow the difficulties of the day to overwhelm them.”

The visual images, Paul says, are the least challenging aspect of cartooning. “Being a cartoonist assumes a level of competence as an artist. But art is just the vehicle. The cartoonist must infuse the image with relevance and meaning, fit the creation into a social context while seeking to ensure that the finished effort makes a point that can be grasped quickly and easily. The deformities in the cartoon characters, the witticisms in the utterances and the minute artistic details are all, in their respective ways, critically relevant to a complete offering in which all the parts must work in unison when it confronts the acid test of viewer comprehension.”

On the other hand it is the nature of the medium that facilitates the mission of the cartoonist. Art is an economical language. It possesses a facility for subtlety that the spoken word cannot quite emulate and requires decidedly less space in which to communicate complex messages. “Often,” Paul says, “the most profound point can be made with little more than the stroke of a brush;” and disfigurement is the cartoonist’s decoy that infuses humour into underlying messages that can be as harsh, as blunt and as devastatingly clear as any editorial The funny visual image is the cloak that conceals the social comment – a kind of dumb but ill-concealed insolence that sobers and amuses, simultaneously.

Studies of the mass media in Guyana have paid scant attention to the role of the cartoon. Ironically, the protracted public and political controversy over media freedom in Guyana has enhanced the relevance of the cartoon. The cartoon, Paul believes, walks the line, wresting its freedom from its capacity to clothe serious comment in cloaks of hilarity, posing a far more difficult challenge to censorial tendencies than the lesser subtleties of the written word. How to cope with the mixed messages of the cleverly contrived cartoon is not a pursuit that censors anywhere have managed to thoroughly master.

When you ask Paul to talk about where he locates himself as a media practitioner he appears uncertain as to how to respond. “Both the print journalist and the cartoonist draw on the same resource, information. The difference is that we present our findings through different media. Our mission, however, is the same. Both the journalist and the cartoonist seek to communicate with their audiences as effectively as their respective skills allow.”

The cartoonist, he says, has “different” challenges. “Time and space are not on the cartoonist’s side. Every nuance, every detail has to fit into a confined space and there is a sense in which the cartoonist must read his work in the same way that the journalist does. If the image fails to make the point, if the viewer fails to grasp its essence, the effort is lost. The facility for elaboration, for retrieval, that is available to the print journalist is not at the disposal of the cartoonist.

It is this challenge, Paul says, that renders the role of the cartoonist unique. The cartoonist does not have the advantages of the gallery artist. Gallery art affords the facility of viewer contemplation of time-consuming introspection. The cartoon is afforded no such luxury. Its critic seeks instant comprehension and gratification.

Paul believes that the creative imagination of the cartoonist differs significantly from that of the print journalist. There are, he says, flexibilities in the abstract nature of the visual image that go far beyond the boundaries of language. “Language, for all its range and flexibility can never really ‘manufacture’ the myriad subtleties and nuances that art can. Artistic abstractions cannot be easily and economically emulated in the written word.”

Paul insists that the really effective cartoonist has to be a “thinking creature.” Reading, he says, is “a must;” not only reading but comprehending with a level of clarity that allows for both correct interpretation and for depth of understanding that facilitates clear and unambiguous presentation for the audience. “You have to be sure that you understand the issue clearly before you commit that issue to a cartoon,” Paul says.

Paul appears surprisingly indifferent to the feedback which his work elicits. “Sometimes things occur or do not occur to people depending on the manner in which it is presented to them. People who comment on my work are often grateful for the gratification that inheres in its simplicity. Making complex things simple, unravelling mysteries, making things clear without actually saying them is part of the skill of cartooning.”