By Brendan de Caires

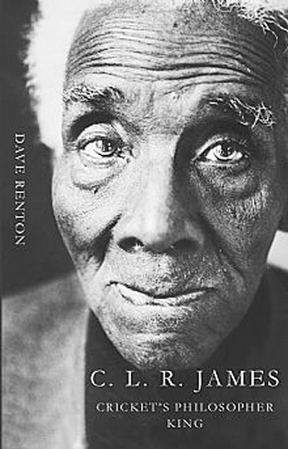

C.L.R. James: Cricket’s Philosopher King, by Dave Renton (Haus Publishing, ISBN ISBN 78-1905791019, 192 pp)

Urbane Revolutionary: C.L.R. James and the Struggle for a New Society, by Frank Rosengarten (University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 978-1934110263, 282 pp)

In 1979, I watched rioters topple the boundary fence at the Bourda cricket ground in Georgetown and strafe the pavilion with soft-drink bottles. The Packer World Series had been plagued with rain delays, and now the crowd could take no more. Although I was only nine years old, I managed to throw a chair into the outfield before being spirited away to safety. Mounted policemen entered the grounds soon afterwards and used tear gas to bring the local sans-culottes under control.

Had I not seen Vivian Richards face Australia’s demon quicks at this very ground, the riot would have been the headiest moment of my young life. But I had seen him, and thirty years later I cannot forget his electric nonchalance: the leonine grace with which he strolled towards the batting strip, unhelmeted, bat swinging like a sword, while he sized up the fielders as though deciding whom to punish first. Richards was to cricket what Lenny Bruce had been to comedy, or Marlon Brando to acting: his dangerous intensity made it into something else, something closer to prizefighting, perhaps even “the continuation of politics by other means.” His defiance was palpable at a thousand yards. Before he reached the bottom of the pavilion steps, you could feel the atmosphere change. By the time he had taken his guard, we were leaning forward in anticipation, anxious for Lillee and Thomson, Australia’s schoolyard bullies, to get their due. He didn’t disappoint.

CLR James understood this drama better than anyone else. He read cricket, and nearly everything else, in terms of tradition and the individual talent.

When he wrote about it, his inner novelist tended to overwhelm the historian, but they often worked in tandem, recording an experience, then, unobtrusively, decoding it. In many ways, he was the Lytton Strachey of cricket, brilliantly reanimating historical figures within their contemporary world, to show how their lives contained what he called “the future in the present.” Like Strachey, James was always skeptical of received wisdom and easy parallels. While examining WG Grace’s formidable adaptability — to fast bowlers, slow tracks, even the “new phenomenon of balls curling in the air” — he warns us: “WG’s batting figures, remarkable as they are, lose all their true significance unless they are seen in close relation with the history of cricket itself and the social history of England. Unless you do that you fall head foremost into the trap of making comparisons with Bradman.

Bradman piled up centuries. WG built a social organisation.”

James must have seen Richards as a revolutionary, more Dessalines than L’Ouverture, a Byronic figure among the professionals who had taken West Indies cricket to its astonishing ascendancy, someone who delivered the thrill that audiences sought from gangster movies in Depression-era America. “In such a society,” he had written, “the individual demands an aesthetic compensation in the contemplation of free individuals who go out into the world and settle their problems by free activity and individualistic methods. In these perpetual isolated wars free individuals are pitted against free individuals, live grandly and boldly. What they want, they go for.” In 1979, Georgetown was in dire need of aesthetic compensation — though few of us would have called it that. Richards’ batting was one form, rioting another.

James must have seen Richards as a revolutionary, more Dessalines than L’Ouverture, a Byronic figure among the professionals who had taken West Indies cricket to its astonishing ascendancy, someone who delivered the thrill that audiences sought from gangster movies in Depression-era America. “In such a society,” he had written, “the individual demands an aesthetic compensation in the contemplation of free individuals who go out into the world and settle their problems by free activity and individualistic methods. In these perpetual isolated wars free individuals are pitted against free individuals, live grandly and boldly. What they want, they go for.” In 1979, Georgetown was in dire need of aesthetic compensation — though few of us would have called it that. Richards’ batting was one form, rioting another.

In his introduction to Cricket’s Philosopher King, Dave Renton, a sociology professor and biographer of Trotsky, refers to a “disturbing lapse in radical theory”:

. . . that there are not more writers setting out urgently to explain the triumph of Brian Lara’s 375 or the bathos of his 400, the success of Flintoff and Pietersen’s charge against Lee and Kasprowicz at Edgbaston in 2005, the contrast between the weight of India within the sport’s upper echelons and its underperformance (until recently) of the national Test side.

Renton hopes his book will “persuade Marxists of the joys of cricket, and followers of cricket of the calibre of James and James’s Marxism.” No small task for any book, much less one of 180 pages (at least a dozen of which are given over to lavish black and white photographs and captions). Perhaps inevitably, there are sins of omission.

Renton moves briskly, using footnotes to gloss some of the bit players in James’s remarkable life. James Burnham, Raya Dunayevskaya (Trotsky’s former secretary), Richard Wright, Trotsky himself, and Naipaul are summed up in five lines, the dialectic (in Socrates and Hegel) in eight; George Padmore, Paul Robeson, and Learie Constantine, deservedly, get more than ten. Generally this works quite well, but it soon becomes clear that there won’t be enough room for both politics and cricket. Too often, given the book’s stated aims, politics dominates. Instead of radical analysis of Lara — has Renton read Hillary Beckles? — we mostly get a readable précis of the well-trodden ground of intra-party Marxist squabbling and CLR’s foray into the wider political world of African and West Indian nationalism. Renton does his best to keep the story close to his “cricketing Marxist” frame, but James is too multifarious, his life too Odyssean to conform to the schema.

In a dozen pages we move from Robeson playing Toussaint at the Westminster Theatre, to James researching The Black Jacobins in Paris, then cricket journalism at the Glasgow Herald, his translation of Boris Souvarine’s Stalin, and the famous week-long meeting with Trotsky in Mexico. Each episode cries out for fuller treatment, especially when we briefly detour into James’s colourful private life. In Paris, for instance, living with his fellow activist Louise Cripps, we are told:

He was humorous. He was a kind and attentive lover. They discussed having children. But she was married; his wages could not feed three. An abortion was required. Their relationship ended, it began again. There was a second abortion. There were also political differences . . .

This telegraphese keeps the plot moving, but it is immensely frustrating to anyone who wants to know more about the human complexity of our finest literary mind struggling over one of his masterpieces. We are told that Cripps found him “very proud, and in some ways, a very arrogant man. You had to agree with him on what he thought.” But instead of pausing over these suggestive details, to confirm or refute, the story bounds on to James’s cricket journalism and his opinions of various attempts to modernise the game.

Occasionally Renton goes behind the accepted version and the story takes an unexpected turn. A case in point is the cinema boycott in the Lancashire town of Nelson — “Little Moscow” to some of its critics — where James lived for a time with Constantine. In James’s version, in an essay collected in Letters from London, when the owners of the local cinema tried to cut wages covertly,

. . . the Nelson people got wind of the matter. There were meetings and discussions. They decided that the salaries of the cinema operators should not be lowered. Complications began. The owners insisted. One cannot be certain of the details. But what matters is that the whole town of Nelson, so to speak, went on strike . . .[until] the company went bankrupt and had to leave. Whereupon local people took over and the theatres again began to be filled.

The incident is not recorded in the Nelson library, nor in the pages of the North West Labour History. Renton speculates that we might read James’s account “as a statement of what people in the town would have liked to have done, or really ‘should’ have done in light of their local reputation. For the year of James’s arrival also witnessed the well-documented More Looms Dispute of the Nelson weavers.” The discrepancy opens up several intriguing possibilities. Did James knowingly embrace a fictional strike for ideological purposes, did he embellish the cinemagoers protest with the weavers, or did he just stretch the truth a little to emphasise working-class solidarity? Either way, Nelson’s radicals changed James forever. He later wrote: “My labour and socialist ideas had been got from books and were rather abstract. These cynical working men were a revelation and brought me down to earth.”

When James moves to America, Renton’s bare-bones narrative style pays off handsomely. We get, for example, this wonderful vignette of CLR speaking in Los Angeles, seen through the eyes of the beautiful Constance Webb, later his second wife:

He was over six feet two inches, slim, but not thin, with long legs. He walked easily, with his shoulders level. His head appeared to be on a stalk, held high with the chin tilted forward and up, which made it seem that his body was led by a long neck, curved forward like that of a racehorse in the slip. Shoulders, chest, and legs were powerful and he moved decisively. But as with highly trained athletes, the tension was concentrated and tuned, so that he gave the impression of enormous ease. He was without self-consciousness, simply himself, which showed in the way he moved, and one recognised a special quality.

The mystery of this thoroughbred’s subsequent entanglement in “what his biographers often treat as the sad conspiracies of a fringe” is deftly handled. Renton clearly appreciates the nuances of the Johnson-Forest Tendency — the Trotskyite sect that consumed most of James’s energy in his American years; “JR Johnson” was James’s pseudonym, “Freddie Forest” that of Raya Dunayevskaya — but he mercifully passes over all but a few of the details. The defection of James Burnham is one of these exceptions and, given the influence he would exercise over American conservatives in the following decades, a well-chosen one.

James Burnham left the Workers Party in 1940, defending an abstract-sounding position, that a “managerial revolution” had taken place in Russia in 1917, 1921, or 1928. Behind this phrase Burnham was saying that the left should support the war effort. The only choice remaining to the world was between American liberalism and German or Soviet fascism. The left had a moral duty to endorse American liberalism. But if socialists endorsed the US then would they remain revolutionary? Was there no choice other than to back either of the empires? “A man of remarkable intellect and great strength of character,” James told Webb, “has crawled out of the revolutionary movement by the back door; today stands nowhere; tomorrow will have to stand with the bourgeoisie, for society offers you no third choice in this crisis.” James was right. Within months of leaving the party, Burnham had become a prominent conservative.

However Byzantine the political intrigues of these years seem now, they clearly engaged James fully. When finally forced to leave America in 1953, he returned to a Britain that had no real place for him. By chance, George Lamming ran into him on Charing Cross Road in 1954, and found James in poor physical condition. “When he said ‘Lamming’ and I said ‘Yes’, I was very excited and a little shocked when he told me who he was.” The ennui of these years sounds dreadful: “Lamming also claimed that James liked to spend his days playing pinball in the arcades in Soho.” The Suez crisis and the uprising in Hungary offered opportunities for “renewed agitation,” and Renton observes that “James should have been the prophet of the hour. Yet following his disappointment in America, and ignoring the major organisations of the British left as if they were moribund, James had little influence on the new movement.”

Of course, the story is far from over. When James returned to Trinidad in 1958, at the invitation of the People’s National Movement, he became embroiled in far more consequential political quarrels. Renton’s coverage of these years adds little to what a West Indian will already know, but he does unearth a few gems. After relations with Eric Williams soured, James told a journalist: “It is [well] recognised that for the first time in the island there is someone who is perfectly able to take care of Williams in debate, public authority, and political competence. That person is myself.” On another occasion, he wrote to ANR Robinson to grouse about the lack of support for the party newspaper, which was James editing:

In all my experience I have never known or heard of any paper, least of all an official organ, which in editorial range and point, production, advertisements, circulation, starting with a grossly incompetent accountant, a disloyal assistant, an office boy, a borrowed typewriter, one filing cabinet and one desk, has reached where The Nation has reached . . .

Two late chapters do their best to compensate for the book’s relative neglect of the central role which literary and cultural criticism played in James’s life, and to give a better sense of how Constantine’s cricket revealed to him that “They (the English) are no better than we.” Fittingly, Renton delves into some of the political issues, such as James’s claim in Beyond a Boundary that the decline of English cricket after 1914 was linked to the country’s waning imperial ambitions.

Bodyline was the key episode, as an English cricket team incapable of maintaining its hegemony through talent or influence turned to violence, shredding the vestigial influence of the public school morality. Decline continued through the 1950s . . . (when James observed) a tendency towards the more defensive playing of spin. Such cricketers as Cowdrey, Graveney, and May, had become overly pre-occupied with the defence, James insisted.

“These are the Welfare Staters,” he wrote.

A few thoughts about cricket’s cultural ambivalence (it “can be the means by which racial hierarchies are reinforced or one means by which they can be overthrown”) lead into the question of what connects Constantine to James’s other heroes. A major consideration seems to have been the Procrustean demands of league cricket, which:

unlike its first-class counterpart, was a single innings game. Constantine’s style in this setting, James argues, was to bat in a way that was both orthodox and dissident: first he would settle, next he would score around the ground, until the field was widely set. Then he would accumulate patiently. Nothing was left to chance, but to

talent and the habit of success.

Here we approach one of the great James questions, namely: how did he believe the genius of the West Indies was expressed by its cricketers? Arguably, most of his heroes — Constantine, Headley, Worrell, Sobers, and Kanhai — were heirs to WG Grace’s restless spirit; they improvised shots and adopted new tactics and strategies as playing conditions changed. They didn’t violate the public school values at the heart of the game (appeal only when you think the batsman is out, never question the umpire, don’t make excuses), but through force of character, and exceptional athleticism, they led it off in new directions.

Some have claimed that James was too embedded in Britain’s imperial culture to achieve the detachment his politics demanded. (As a teenager he read Vanity Fair more than a dozen times, and could quote large parts of it at will; in later life he quipped that “Thackeray, not Marx, bears the heaviest responsibility for me.”) But this criticism does not bear analysis. James was always drawn to writers who seemed to have intuited the future from contemporary political tensions. For him, Thackeray’s send-up of the Victorian bourgeoisie was a natural prologue to Trotsky’s vision of the end to class struggle; Melville’s doubts about the soulless materialism of pre-Civil War America were comparable to Marx’s prescient suspicions, twenty years later, that Europe was about to implode. In James’s analysis, each of these writers glimpsed part of what lay ahead, and they dared to imagine the whole. In many ways, WG Grace is their cricketing counterpart, for he took the game where it had to go: away from the professionals. By opening it up to the common man, he began a revolution (dialectical progress?) that would reshape both the game and the societies that played it.

Cricket’s heroes change their style to suit most technical and political challenges, but when they must they also change the game. James saw hints of this throughout his days as a cricket correspondent, right up to the end. In 1985, writing about Ian Botham, the only English player who could have held his own in Clive Lloyd’s great West Indies side, James observes:

Botham’s hitting is regulated according to custom and in the tradition of the great orthodox batsmen. He is not exact orthodox. A great batsman never is. The infallible sign of greatness is that somewhere in his method he is breaking the rules, or if not rules, the practices of his distinguished equals . . . Let no one think that an article of a few hundred words can deal with Botham. There will be plenty more later.

Renton observes that a revised Beyond a Boundary ought to have included a chapter on Viv Richards’s team “taking pleasure in their exuberance with the bat, the ball, and in the field, and commenting on the relationship between Richards and his audience. The end of direct colonial rule was still within the memory of the older players of the side.” He also notes the “generosity of spirit” that led James to dedicate his last pieces of cricket journalism “to the star player in the rival team.”

Frank Rosengarten’s life of James, Urbane Revolutionary: C.L.R. James and the Struggle for a New Society, is an altogether more scholarly affair. Page after page is filled with scrupulously detailed political analysis, unleavened by references to James’s other interests, even though much of James’s Marxism sounds germane to his views on cricket. Consider the following passage, which discusses Notes on Dialectics, James’s laudable effort to demystify Marx and Hegel for the common man. Mutatis mutandis, it could easily be part of Beyond a Boundary:

. . . the unifying principle of part 2 is the notion of Aufhebung, whereby a historical phenomenon such as a political party or a labour federation not only absorbs into itself the features of earlier forms of organisation but moves beyond and transcends them, thus producing a new synthesis of forms qualitatively superior to its predecessors . . . for James a pivotal point in the Hegelian system is that “things instead of being left in their immediacy, must be shown to be mediated by, or upon, something else.” For Hegel, and for James, thought must always be relational.

That quibble aside, Urbane Revolu-tionary is essential reading for anyone interested in the full range of the James oeuvre. Although it is clearly intended for an academic audience, there is much here to reward a diligent general reader. Among the occasionally exhausting analytical passages, there are priceless glimpses of the childlike pleasure James derived from provocative new ideas. On Valentine’s Day in 1955, he wrote William Gorman, a Johnson-Forest colleague who specialised in the history of the American Civil War, to thank him for an essay that contained

the most amazing thesis that has ever been put forward about American history — that the runaway slave, not slavery, nor the “rebellion of the Negroes,” nor the intelligence and revolutionism of the Negroes etc. etc., but the slave running away, awoke and united all the forces for the Second American Revolution. That is something that is ours, and ours alone. Where else could it come from? How KM and VL and LT would have hugged this to their bosoms.

Would Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky have welcomed Gorman’s thesis quite so warmly? I have no idea, but I find James’s enthusiasm on their behalf very endearing.

Much of Rosengarten’s book inches its way through with the arcana of the Johnson-Forest debates — was Stalinist Russia an example of “state capitalism,” or Lenin a “crude materialist”? Most of this lies beyond my competence, but I was intrigued by Trotsky’s reservation about Notes, which he thought a “very good book,” but one that suffered from “a lack of dialectical approach, Anglo-Saxon empiricism, and formalism which is only the reverse of empiricism.” Renton, who also quotes this observation, fastens onto the accusation of “formalism” and decodes it into this:

“Trotsky detected in James a tendency to discuss real people and changing personal experiences as if they were categories to be fitted into boxes (philosophy X, error Y), without a need to understand the historical dynamics at work in people’s lives.” I suspect that Trotsky was also onto something with the “Anglo-Saxon” part of his dismissal. Like Samuel Johnson, who famously kicked a stone to “refute” what he thought was an over-subtle piece of philosophising, James does not seem to have yielded to the obscurantism that characterises so much Marxist theory. Elsewhere, Rosengarten tells us that “one of the traits that James most admired in Lenin [was] the courage to break through rhetorical verbiage in order to pinpoint the real problems facing the revolutionary regime at a critical transitional stage in its development.”

Other Anglo-Saxon tendencies explain several of James’s disputes with fellow Marxists. Life in Nelson had given him a problematic belief in what one critic calls “the capacity of the seemingly incoherent crowd, united by common experience and common grievances, to engage in concerted action.” Apparently this was anathema to more than one eminent Trotskyite.

When Johnson-Forest fell out with the US Workers Party, no less a figure than Irving Howe offered the following indictment:

The basic error underlying Johnson’s [i.e. James’s] approach to every political question is his constant underestimation of the role of the party in our epoch. He constantly speaks of the “self-activity” of the working class as if that were some magical panacea . . . The working class cannot conquer power by “self-activity” or “self-mobilisation”; it can conquer power only under the leadership of a consciously revolutionary and democratic socialist party

James met criticism like this with remarkable self-confidence, but he also seems to have been willing to revisit cherished political ideals when real-world circumstances made them grossly impractical. The most striking instance of this came after he formed the Workers and Farmers Party in Trinidad, to compete against the now-estranged PNM. As part of a drive to expand the base of the new party, James had to court “East Indian merchants and shopkeepers, landowners and accountants,” and other ideologically suspect characters. He tried to argue that:

Throwing in their lot with the nation’s workers and farmers and joining forces with the WFP . . . would mean “bigger and better business for you.

Better business, More Profits, More Opportunities for people with energy, an eye for the quick (and honest) dollar.”

It didn’t work and the WFP’s dismal performance in the elections provoked one of the most uncharacteristic responses of James’s whole life.

Rosengarten tells us that “in several letters to friends in the United States he voiced his opinion in words that have become familiar to many Americans during the Bush presidency: ‘They robbed us. Everybody agrees, everybody.

The machines were rigged.’”

The final section of Urbane Revolutionary is devoted to James’s cultural and literary criticism. It is as meticulous as the chapters on Marxism.

Throughout the book, Rosengarten maintains an enviable scholarly detachment from James, a willingness to admit that even Homer nods, occasionally at some length. I’m not entirely hopeful that every reader will approach the question of how James reconciled “Heideggerian and Sartrean existential philosophy with his insistence on the primacy of the social and of the national-popular in the production of literature that speaks to the masses” with the same relish that I did, but if you are prepared to wrestle with this kind of highbrow analysis, then Rosengarten’s volume is indispensable.

In the summer of 1953, we are told, James “assumed the task of challenging English critics who he felt had proven their intellectual brilliance and virtuosity but at the same time had taken the literary-critical enterprise down the wrong path, towards ever more specialised forms of analysis.”

When he discovered that one of the chief culprits, William Empson, lived near his North London flat, James bought one of his books — Seven Types of Ambiguity — but found it unreadable, something which “happens to me once every five years.”

What amazed James about Empson, a poet as well as a critic, was that he had “gotten into a feud about a single line in a Shakespeare sonnet” with another critic, F.W. Bateson, a dispute which James called “the ultimate in foolishness”

Rosengarten adds that it was probably James’s passion for clarity, his “preference for eliminating ambiguity,” that made him reject Empson’s “argument for the polysemous nature of any literary text.” I suspect that his distaste for the cloistered existence which allowed intelligent men to succumb to such navelgazing had something to do with it as well.

“With hindsight, James does seem to have been wrong about almost everything in politics,” said biographer and broadcaster Humphrey Carpenter in a BBC Radio retrospective in 2002. “He was wrong about Africa, he was wrong about America — believing it would become socialist — he was wrong about Soviet Russia and about world revolution. Surely this lowers your opinion of him a bit?” I cannot remember the response from Darcus Howe, James’s great-nephew, but later in the programme Carpenter played a recording of the man himself speaking about his greatest book, and his reply reminded me that some political errors are much greater than others:

I was tired of reading [that] all blacks were in trouble in Africa, then [after] they made the Middle Passage they were in more trouble, then they landed in America and they landed in the Caribbean and they were constantly in trouble, and I got very tired of it. I said I want to find some story where blacks are doing things to people and not being done things by people. So I made up my mind when I went to England, which I intended, I would write about Toussaint L’Ouverture.

Urbane revolutionary or philosopher king? James was both, and much more. Whatever his political failings, however untidy his private life, surely Caryl Phillips is correct when he writes that “in a century that has produced talents as diverse as the economist Arthur Lewis, the poets Derek Walcott and Aimé Césaire, and the novelist Alejo Carpentier, there is little doubt that James will come to be regarded as the outstanding Caribbean mind of the twentieth century.”

detected in James a tendency to discuss real people and changing personal experiences as if they were categories to be fitted into boxes (philosophy X, error Y), without a need to understand the historical dynamics at work in people’s lives.” I suspect that Trotsky was also onto something with the “Anglo-Saxon” part of his dismissal. Like Samuel Johnson, who famously kicked a stone to “refute” what he thought was an over-subtle piece of philosophising, James does not seem to have yielded to the obscurantism that characterises so much Marxist theory. Elsewhere, Rosengarten tells us that “one of the traits that James most admired in Lenin [was] the courage to break through rhetorical verbiage in order to pinpoint the real problems facing the revolutionary regime at a critical transitional stage in its development.”

Other Anglo-Saxon tendencies explain several of James’s disputes with fellow Marxists. Life in Nelson had given him a problematic belief in what one critic calls “the capacity of the seemingly incoherent crowd, united by common experience and common grievances, to engage in concerted action.” Apparently this was anathema to more than one eminent Trotskyite.

When Johnson-Forest fell out with the US Workers Party, no less a figure than Irving Howe offered the following indictment:

The basic error underlying Johnson’s (i.e. James’s) approach to every political question is his constant underestimation of the role of the party in our epoch. He constantly speaks of the “self-activity” of the working class as if that were some magical panacea . . . The working class cannot conquer power by “self-activity” or “self-mobilisation”; it can conquer power only under the leadership of a consciously revolutionary and democratic socialist party

James met criticism like this with remarkable self-confidence, but he also seems to have been willing to revisit cherished political ideals when real-world circumstances made them grossly impractical. The most striking instance of this came after he formed the Workers and Farmers Party in Trinidad, to compete against the now-estranged PNM. As part of a drive to expand the base of the new party, James had to court “East Indian merchants and shopkeepers, landowners and accountants,” and other ideologically suspect characters. He tried to argue that:

Throwing in their lot with the nation’s workers and farmers and joining forces with the WFP . . . would mean “bigger and better business for you.

Better business, More Profits, More Opportunities for people with energy, an eye for the quick (and honest) dollar.”

It didn’t work and the WFP’s dismal performance in the elections provoked one of the most uncharacteristic responses of James’s whole life.

Rosengarten tells us that “in several letters to friends in the United States he voiced his opinion in words that have become familiar to many Americans during the Bush presidency: ‘They robbed us. Everybody agrees, everybody. The machines were rigged.’”

The final section of Urbane Revolutionary is devoted to James’s cultural and literary criticism. It is as meticulous as the chapters on Marxism.

Throughout the book, Rosengarten maintains an enviable scholarly detachment from James, a willingness to admit that even Homer nods, occasionally at some length. I’m not entirely hopeful that every reader will approach the question of how James reconciled “Heideggerian and Sartrean existential philosophy with his insistence on the primacy of the social and of the national-popular in the production of literature that speaks to the masses” with the same relish that I did, but if you are prepared to wrestle with this kind of highbrow analysis, then Rosengarten’s volume is indispensable.

In the summer of 1953, we are told, James “assumed the task of challenging English critics who he felt had proven their intellectual brilliance and virtuosity but at the same time had taken the literary-critical enterprise down the wrong path, towards ever more specialised forms of analysis.”

When he discovered that one of the chief culprits, William Empson, lived near his North London flat, James bought one of his books — Seven Types of Ambiguity — but found it unreadable, something which “happens to me once every five years.”

What amazed James about Empson, a poet as well as a critic, was that he had “gotten into a feud about a single line in a Shakespeare sonnet” with another critic, F.W. Bateson, a dispute which James called “the ultimate in foolishness”.

Rosengarten adds that it was probably James’s passion for clarity, his “preference for eliminating ambiguity,” that made him reject Empson’s “argument for the polysemous nature of any literary text.” I suspect that his distaste for the cloistered existence which allowed intelligent men to succumb to such navel gazing had something to do with it as well.

“With hindsight, James does seem to have been wrong about almost everything in politics,” said biographer and broadcaster Humphrey Carpenter in a BBC Radio retrospective in 2002. “He was wrong about Africa, he was wrong about America — believing it would become socialist — he was wrong about Soviet Russia and about world revolution. Surely this lowers your opinion of him a bit?” I cannot remember the response from Darcus Howe, James’s great-nephew, but later in the programme Carpenter played a recording of the man himself speaking about his greatest book, and his reply reminded me that some political errors are much greater than others:

I was tired of reading (that) all blacks were in trouble in Africa, then (after) they made the Middle Passage they were in more trouble, then they landed in America and they landed in the Caribbean and they were constantly in trouble, and I got very tired of it. I said I want to find some story where blacks are doing things to people and not being done things by people. So I made up my mind when I went to England, which I intended, I would write about Toussaint L’Ouverture.

Urbane revolutionary or philosopher king? James was both, and much more. Whatever his political failings, however untidy his private life, surely Caryl Phillips is correct when he writes that “in a century that has produced talents as diverse as the economist Arthur Lewis, the poets Derek Walcott and Aimé Césaire, and the novelist Alejo Carpentier, there is little doubt that James will come to be regarded as the outstanding Caribbean mind of the twentieth century.”