During his terminal illness several years ago I had a conversation with the late Aubrey Williams. One of the things that he told me during that conversation was that death holds no domain over the legacy of creative genius.

During his terminal illness several years ago I had a conversation with the late Aubrey Williams. One of the things that he told me during that conversation was that death holds no domain over the legacy of creative genius.

I first reflected on his words during a viewing of some of his paintings at the Commonwealth Institute in London some time after his death.

The poignancy of Aubrey’s thoughts came immediately to mind upon learning of the death of Roy Heath.

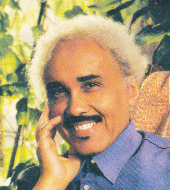

I believe that the passing of Roy Heath has robbed Guyana’s literary community, patrons of the creative arts and students of Guyanese and Caribbean literature of a creative genius – and here I stress that I use the phrase (creative genius) in its absolutely literal sense. Roy Health (like Aubrey Williams) has left a rich legacy of creative writing behind and even if that legacy does not compensate for his earthly end it at least serves – at least to me – as a reminder that creative people truly live on through their legacies.

I have found in some Caribbean literary critics a tendency to compare our writers – perhaps with a few exceptions – with each other, ever reluctant, it seems, to make comparisons with the great writers beyond the region. I am thankful that I’m able to assess the works of Roy Heath against literary efforts that transcend the Caribbean – and here I hasten to add that I do not seek in any way to devalue the region’s contribution to the global literary tapestry.

Roy Heath was, in my view, truly one of the most brilliant story tellers ever. He was, as well, unquestionably one of Guyana’s most prolific novelists and my own favourite Caribbean novelist (I suppose I too am guilty of the practice of making comparisons among Caribbean writers) along with another Guyanese, Rooplall Monar and the Trinidadian novelist Earl Lovelace.

Roy Heath was, in my view, truly one of the most brilliant story tellers ever. He was, as well, unquestionably one of Guyana’s most prolific novelists and my own favourite Caribbean novelist (I suppose I too am guilty of the practice of making comparisons among Caribbean writers) along with another Guyanese, Rooplall Monar and the Trinidadian novelist Earl Lovelace.

I remember that it was Aubrey Williams who introduced me, first, to the writings of Roy Heath and subsequently to Health himself. After I had read his excellent trilogy – Genetha, The Murderer and One Generation – I simply ferreted out every novel of his that I could find.

There are several generations of Guyanese whom, like myself, encountered the West Indian novel relatively late in life. The problem here is that our school curricula tended to be biased towards Shakespeare, Shelley et al.

Official appreciation of the role of the West Indian novel as part of the school curriculum came later – during the mid to late 1970s I think.

That accounts, I suppose, for my late introduction to Roy Heath.

Fortuitously, my discovery of Heath’s works occurred in London where most West Indian novels are published and where there is a surfeit of bookstores that stock West Indian novels. Acquisition, therefore, was easy.

I admired Roy Heath for – above all else – the manner in which he combined clarity and simplicity in his use of language. It seemed to me that he always went to great and deliberate lengths to cut through the complexity of language, to simplify the art of writing, eschewing stylistic options – ever present in the work of other West Indian novelists who will remain unnamed – that sometimes seem to set far more store by parading a facility for language than communicating with people.

It is primarily for this reason that I had always felt that Heath’s works were perhaps ideally suited to schools’ curriculum and ought to feature far more in the education of our children. You will find in the Heath novel the epitome of well written prose in addition to which the themes of his novels provide valuable lessons in aspects of Guyanese history, culture and sociology apart from being, in themselves, delightfully entertaining stories.

Before I met Roy Heath – I do not recall meeting him more than once – I had fashioned a mental picture of the man in my head – earthy, matter-of-fact, and incurably Guyanese; and that was just what he turned out to be in real life, a creative genius who appeared to me to have settled for a life ‘in exile’ without really having embraced the idea of being an Englishman.

I had found too that Roy Heath, to a far greater extent than any other Guyanese novelist, displayed both an appetite and a talent for exploring urban Guyanese themes. The physical architecture and the middle class life styles of mid-twentieth century George-town seemed to feature in his thinking to the extent where he always seemed keen to paint the most painstaking literary pictures of these particular images scenes which had obviously been part of his experience of growing up in Guyana.

I remember that one of my more memorable assignments during my posting to the Guyana High Commission in London was my assignment to work with the Guyana Prize for Literature Committee in Georgetown to help popularize the Guyana Prize among our writers in exile. The response, I remember was good. Writers like John Agard, Grace Nicolls, David Dabydeen, Pauline Melville, Beryl Gilroy and Fred D’Aguiar all entered books for the Guyana Prize during its earliest years.

I remember 1989 well. It was the year of Roy Heath’s Shadow Bride – the only novel that – at least as far as I can recall – I have ever read three times.

I remember reading it and talking about it and saying to someone with whom I was liaising from London – it could have been Yvonne Stephenson, the then librarian at the University of Guyana – that I really did not think that the other entries for the Guyana Prize that year stood a chance.

I recall that Heath’s works were popular among Guyanese in London and that when an English teacher from the East End of London asked me one day to help her understand the role of the Guyanese literary tradition in chronicling real-life Guyana I simply took her down Bayswater Road in West London to Mrs Saunderson’s bookshop on Bayswater Road (I will always be grateful to my friend and colleague Ronald Austin, an incurable ‘bookaholic’ for introducing me to Mrs. Saunderson’s bookstore) and saw to it that she bought a few of Heath’s novels. “Read Roy Heath,” I told her. “He will help you find what you are looking for.”

There is a sense of ‘order’ to Heath’s work that makes him undertstandable in a sense that some other writers are not. I remember that the more I read Roy Heath the more I thought that some other West Indian writers wrote with the critics in mind. Heath, in my view, imposed no such restrictions on his own writings. His works, to my mind always reflected an overwhelming confidence in the virtue of crystal clear simplicity.

I have not ever read Heath’s much talked about Tribute to Aubrey Williams but I imagine that it would have been well-informed – the two men knew each other well – perhaps full of witticisms, reflective of the sense of ordinariness that I detected in the personalities of both men. Heath, I imagine, would have employed the same brilliant simplicity that has been part of his trademark as a novelist, to pay tribute to the pre-Colombian symbolism in Williams’ works.

Earlier this year during an interview with Culture Minister Dr Frank Anthony for an article on Carifesta X published in the Guyana Review a few months ago the Minister mentioned to me that as part of the Carifesta programme a national literary collection was being compiled. I got the impression from Dr. Anthony that this was a pursuit that was intended to go beyond Carifesta itself and I found myself applauding what I thought was a long-overdue initiative.

Funny enough, the passing of Roy Heath reminds me of – among other things – how little official attention has been paid to our splendid literary tradition. You really have to live in exile – I suppose – to understand the role that literature has played in putting small countries like Guyana on the map, in providing cause for Guyanese in exile to celebrate their common heritage; and when you contemplate the irony of how little public recognition that body of literature has received at home up to this time, the significance of the idea mentioned by Dr Anthony is put into perspective.

Certainly, Roy Heath belongs in that pantheon of local literary heroes whom Carifesta must seek to honour. Beyond Carifesta itself Roy Heath is deserving of permanent institutional recognition in the annals of Guyanese and Caribbean literature.

I have never met any other member of Roy Heath’s family; I would want those whom he left behind to be aware, however, that he epitomizes the view expressed to me by Aubrey Williams that death, indeed, holds no domain over true creative genius.

Arnon Adams