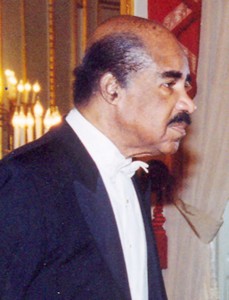

Dr Kenneth Fitzgerald Stanislaus King, former ambassador to the Kingdom of Belgium and Minister of Economic Development, died on July 30 aged 78

It was Kenneth King’s good fortune to have been appointed chief architect to lead the teams that designed the two most ambitious economic development plans in post-independence Guyana. The first, known as the Second Development Plan 1972-1976, was launched by the People’s National Congress administration. The second, the National Development Strategy, was launched by the People’s Progressive Party administration in 1996. It was Guyana’s misfortune that neither was fully implemented much less given a chance to succeed.

Working with a talented team that included Donald Augustin, William D’Andrade and Clarence Ellis, King engineered a plan to create a society that would be self-reliant, egalitarian and grounded in the achievement of Guyanese control over its economic destiny. Remembered only by its slogan to “feed, clothe and house” the people, the development plan was expected idealistically to create employment opportunities, generate equal distribution of incomes and encourage the equitable geographic distribution of economic activities.

The National Development Strategy was the product of the efforts of a cohort of two dozen technical working groups involving more that 200 individuals from the government, business community, university and civil society. This time, King as helmsman aimed more realistically at “solving problems, everywhere identifying concerns and developing solidly-based remedial courses of action that are sustainable.”

The foundation for King’s nearly sixty-year career of public service was laid as a student at Queen’s College which he entered in September 1941. Amidst a class of highly competitive colleagues such as Bertram Collins, Rashleigh Jackson, Pryor Jonas, Frank Noel and Frederick Wills, King breezed through his Oxford and Cambridge School Certificate and London University Higher Certificate examinations. His septennium ended in 1948 after taking over editorship of the school magazine from Shridath Ramphal and with his elevation to prefectship.

After Queens, he taught briefly at St James-the-Less primary school in Kitty then joined the British Guiana Civil Service in the Department of Forestry. As a forestry ranger, his elementary duties included supervision of forest permits and leases and sawmilling. But these were enough to win him a scholarship to study forestry at the University of Wales at Bangor. He had already started studies as an external student in law at London University and, through extraordinary effort, continued both courses simultaneously. He was able to gain his Bachelor of Laws in 1956 and to take a first in Forestry for the Bachelor of Science in 1958.

He then earned the Doctor of Philosophy from Oxford in 1963 with his dissertation on land classification techniques and land-use planning. The University of Wales awarded him the Doctor of Science, honoris causa, for his contribution to rural economic development in the tropics in 1980.

King advanced at civil service pace to the position of Assistant Conservator of Forests, 1958-64 during which time he received a Food and Agriculture Organisation forestry fellowship which included visits to Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, Nigeria and Ghana.

He joined the forestry staff of FAO and was selected to be part of a team to establish the Department of Forestry at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. There he was appointed senior lecturer and taught courses on Forest Economics, Policy and Law, engaged in research, and advised the government on its forestry policy and management. He transferred to FAO headquarters in Rome in 1968 and was appointed Chief of Forestry Development Planning in 1968-70 and Forestry and Land Use Officer with the FAO-World Bank cooperative programme in 1970-71.

It was as an academic that he conceptualised the idea that eventually became known as agroforestry. While at the University of Ibadan, he wrote a paper: ‘Agri-Silviculture (The Taungya System).’ He subsequently co-authored a raft of technical papers which included ‘The Wasted Lands’ and ‘Agro-forestry and the Utilisation of Fragile Ecosystems.’ This was important. Up to the 1960s, the common policy was to exclude citizens from state forests and reserves on the grounds that their presence would impede the management or regeneration of the forests.

As a result of the drought and famine in the Sahel in the mid-1970s which was blamed partially on deforestation, the FAO under King’s guidance embraced a policy of ‘community forestry’ aimed at introducing modern management techniques to forest communities and at ensuring that those citizens benefited from forestry development. Agro-Forestry, a land use system, combining agriculture and forestry, producing both food and wood for fuel for subsistence and sale, was now on the international development agenda. King’s vision and leadership led in 1978 to the FAO’s establishment of the International Centre for Research in Agro-Forestry in Nairobi, Kenya, of which King was appointed the first director general.

King had before that interrupted his promising international career to join the PNC administration where he was appointed Minister of Economic Development and Vice-Chairman of the Guyana State Corporation, the omnibus holding company for the ever-increasing number of state-owned corporations. It was at this time that he led the effort to draft the second development plan.

Easily one of the brightest ministers in Prime Minister Forbes Burnham’s cabinet, King was regarded as a newcomer. His impressive academic credentials, international reputation, sterling service and meteoric rise infuriated his antagonists. Moreover, he was prepared to argue his case cogently and courageously in the cabinet, challenging Burnham who did not curb King’s enthusiasm. His panache and apparent privilege did not go unnoticed by some of his less able but more ambitious colleagues, who nourished hopes of inheriting higher office on grounds of long service and fawning fidelity to the party leader. This made King uncomfortable and he felt that his position had become untenable. Rather abruptly, he quit the cabinet and returned to the tranquillity of the FAO in 1974. In any event, the development plan had already been thrown into disarray by the combination of the external shocks caused by the surge in fuel prices by the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries and by the internal political opposition.

Yet, after President Forbes Burnham’s death when the economy was at its weakest, King willingly came back.

By then, the administration of President Desmond Hoyte had redefined the philosophical basis of the economy. Market-driven private investment was seen as essential to economic recovery and a structural adjustment programme had been introduced.

But problems plagued the opaque programme to divest the state corporations. Public opinion was particularly outraged at the astonishing arrangements for the sale of the assets of the Guyana Telecommunications Corporation and Demerara Woods Limited, negotiations for both of which were concluded with a single buyer. After the sudden resignation of the Deputy Prime Minister who had responsibility for Planning and Development and for the privatisation programme in April, King was invited back and appointed Presidential Adviser on Development and Administration on May 1, 1991 with responsibility for overseeing privatisation.

King’s acuity and integrity quickly restored credibility to the privatisation process. He explained his new approach by stating honestly, “I don’t feel pressed to sell anything in Guyana…What we will do is to make an assessment of the offers and, if the assessment is not good enough, we will not sell.”

After the elections of 1992, King stuck with the losing PNC to serve as a member of the National Assembly where he became an articulate spokesman on economic affairs. And, after several changes at the party’s Congress Place headquarters, he took what turned out to be the poisoned chalice of the general secretaryship. Soon afterwards, however, he demitted that office.

The PPP administration then invited King to serve as Ambassador to the Kingdom of Belgium in Brussels and permanent representative to the European Union to replace Dr Havelock Brewster. He presented his letters of credence to King Albert II in January 2002 but, unfortunately, he was overcome by chronic illness and was obliged to resign his position and return home.

Urbane yet determined in the pursuit of his objectives, King defied pigeonholing as a political player. He saw himself as an agent of change − a professional technocrat rather than a political technician. This was evident from the ease with which he could move from the international to the national and from PNC general secretaryship to PPP-appointed ambassadorship. His loyalty was not to party leaders but to the ordinary people whose miserable lives he tried so hard and so long to transform.

Kenneth Fitzgerald Stanislaus King was born on August 22, 1929 in Cummingsburg, Georgetown. A Congregationalist at first, he later converted to Anglicanism, serving as an altar-boy at St George’s Cathedral and attending St George’s primary school. There he was fortunate to win three scholarships – the St George’s Centenary; Government County and John Fernandes Ltd – and entered Queen’s College in September 1941.

He married Joyce, née Miller, who died in 2005. They had two children Brian and Karen.