We would like Carifesta X to showcase not only the great cultural talent that this region has spawned over the short period of Caribbean history, but the great philosophical legacy and diverse economic, productive and natural resource capacities that we as a region have to offer.

As Carifesta X builds momentum it becomes clear that some of the several goals that Guyana has set itself in the hosting of the festival are already showing promising signs. The Minister of Culture has insisted that there should be a visible element of sustainability; that Carifesta must involve the people of Guyana at all levels and must leave a mark after the curtains descend on the closing ceremony and the visiting performers depart. There has been some success in the public awareness programme, some pre-festival events, the wide-ranging training programme designed by the Artistic Director, the regional popular promotion sweep and, of special interest here, the project of public art.

Guyana has a few prominent pieces of public art including the 1763 Monument, the Timehri Murals at the international airport and the large mural at the National Cultural Centre. In a very short time, during the run-up to Carifesta, there has been a significant increase in the number of these national icons as a result of the Carifesta art project. There is now the Hikarana Pole, traditional Amerindian art depicting bird spirits by Telford Taylor, Lokono artist of St Cuthbert’s, erected on the forecourt of the Walter Roth Museum. A stretch of the Georgetown Seawall covering some 400 yards is the canvass for an impressive exhibition of child art. A mural depicting Spiritual Connection Between Man and Nature, a theme befitting its location, is now a permanent backdrop for the stage at the famous Umana Yana, painted by George Simon and some of his students at the University of Guyana. Then, the most recent addition to this collection is another George Simon mural at the Cultural Centre.

The University of Guyana has been in very close partnership with the Carifesta management, directorate, personnel and activities, making some of the most important contributions to the festival, including the provision of an Artistic Director and committee chairs. These art projects are an excellent illustration of this collaboration since UG Lecturer and prominent national artist Philbert Gajadhar is Chairman of the Visual Arts for Carifesta, while other UG staff, Akima McPherson and George Simon serve on the committee.

Added to those, for two of the murals, the university has provided the artists themselves.

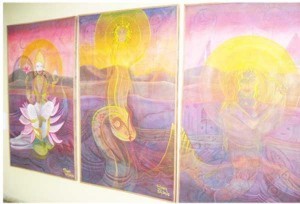

Of these, the grandest and most accomplished is the latest addition, Simon’s Universal Woman that now distinguishes one part of the western wall in the foyer of the Cultural Centre. It is a major work in Guyanese art. An imposing triptych, it is dominated by hues of purple, radiations of golden light and three compelling female figures representing water spirits, the main theme of the painting. Simon investigates the water spirit tradition with specific Guyanese reference, reflecting the belief systems, religious characteristics, folklore characters, ethos, images and symbols of three major Guyanese ethnic worlds. Each section of the work is a portrait of one group, and individually but collectively depicts the Indian, the African and the Amerindian.

Three spirits are studied: the Wata Mama, Ganga Mai and Oriyu. The African Guyanese ‘wata mama’ is associated with lore and religious practice that also have universal resonance. There are close similarities and versions of wata mama reflected in the ribba mumma, mama glo, Simbie, and goddesses of the Santeria, from Jamaica, St Lucia, Haiti and Cuba, as well as the mermaid and the Greek Siren.

This water goddess/spirit has such descriptions as half woman half fish, captivating, appealing body, and long golden hair through which she often runs a golden comb. She habitually lures men to their destruction or condemnation to a life under-water. In Jamaica she may deliberately leave the comb on the river bank for men to find with promise of reward or demise depending on how wisely the situation is handled.

The Siren, who inhabits the high seas, is notorious for her melodious, irresistible, intoxicating singing which captivates men sailing by. If they hear it, they are rendered helpless and are compelled to follow it to their destruction and shipwreck. Yet the river spirits and goddesses of the ocean are given offerings and appeased by religious devotees in Guyana.

Simon interweaves his portrait of Amerindian river spirit Oriyu with the anaconda from which she is said to have descended and other images of serpent energy and Amerindian lore.

The painting draws on tales of the shaman who plants a tree in the middle of the water as an offering to a god to whom the water then becomes sacred. It may be dipped up, taken away and used, but no one is to bathe directly in it. A girl who disobeys this and goes into the water is taken away to the bottom by the male water god to become his wife. Their offspring, half woman, half fish then occasionally comes up to the surface as an Amerindian water spirit/goddess.

The painting further explores the images of the fighting snakes and the caduceus, combined in the staff with the intertwining serpents used as the symbol for medicine and healing. This is also symbolic of the tree planted in the water. Various symbols and beliefs are merged as in the third portrait, that of Ganga Mai. The picture is a typical one, of a Hindu goddess with multiple hands seated in a lotus flower and upon an alligator. She could be Saraswatti, Laxhmie or Ganga Mai.

She is one of the deities of the water in the Kali-Mai puja to whom offerings are made in the temple but also at the river or ocean. The River Ganges in India is sacred to Hinduism, hence the mother of the Ganges, Ganga-Mai. But Ganga Mai is revered in the Kali Mai-religion, which operates outside of mainstream Hinduism and is a hybrid tradition with other elements.

Simon’s choice of female subjects, and his title, Universal Woman, are true to the nature and quality of the spirits and the kind of statement about gender empowerment that he wishes to make. The triptych is as majestic and powerful as the female deities that it studies.

What follows is an excerpt from a description

George Simon: Universal Woman

By Philbert Gajadhar

The severe frontality of George’s art is one of his methods of communing with the women he painted. It is like when he is painting them, he is direct with them and they are direct with him, so they have to face front. His willingness to relax the imperative in the examples at hand may have been because the paintings are in some sense portraits, women who are looking both inward and outward, anxious to harmonise their roles in two worlds […] The decorative aspects of his previous works have vanished. He commenced this painting as pure abstraction and did not add the faces until he had exhausted the design possibilities.

When the proofs were pulled it was obvious that George had achieved a great synthesis, a powerful portrait: the woman as young and ageless as Wata Mama, Ganga Mai and Oriyu.

The geometry that sometimes used to dominate his work is now utterly subservient to an underlying emotion. Universal Woman is an ambivalent woman in dissonant flux, a woman whose internal movements have been externalised by all the irregular, collapsing rectangles and circles. No firm conclusions are possible as to her state of mind – happy? sad? in between? – but her well-being, or lack of it, would prove to be a topic of a heated interpretive dispute wherever she is exhibited.

The painting superficially shares a cubist goal, the desire to depict several surfaces simultaneously, but George is not concerned with recording the conjunctions of physical planes.

His target was rather the multifaceted presentation of psychological levels, and what he achieved is nothing less than a portrait of the maelstrom within the mind. Universal Woman is a map of the psyche, the vaporous interior realm where thought and emotion fall weightlessly and vertiginously, tumbling out of the unknown past into the knowable future. The images are not only or even a portrait of a woman, they are a blueprint of identity, and of identity seen as a product of mercurial and perhaps uncontrollable psychic process forever in transition, in the guise of a female.

The women in the painting are captives in their own geometric elegance. The relationship of the subject to the outside seems perfect. The lines are perfect, perfectly measured, everything is in harmony. The painting is unusual in its symbolism – George’s vision became less specifically symbolic as time went on – but care was nevertheless taken to ensure that the composition would ‘read’ as a harmonious, evocative whole, regardless of the viewer’s background […]