‘One people’

Wan

one tree

so many leaves

one tree

one river

so many creeks

all are going to one sea

one head

so many thoughts

thoughts among which one good one

must be

one God

so many ways of worshipping

but one Father

one Suriname

so many hair types

so many skin colours

so many tongues

one people

Robin Dobru

To be described as Janus-faced is no compliment. It suggests qualities of duplicity, hypocrisy and insincerity, yet literature also draws from this Roman god many progressive and forward-looking metaphors. Janus stands at the beginning of the year in the Roman calendar like the month that bears his name, one face reviewing the year just ended and the other looking forward to the new one that lies ahead. He is the god of gates and beginnings. His two-faced image is a symbol drawing value from the past in order to move with strength and depth into the future.

Related to that is the symbolic power of a Guyanese monument, the historic Kykoveral. What is now a relic was once an important fort to the Dutch colony of Essequibo, a strategically placed look-out and a provision of defence against any hostile convoy attempting to move up the mighty river. It now speaks of national heritage and one of the strengths of the country’s future in tourism. But it is one of the most visible images of Guyanese culture and was very neatly adopted as the name of the most important and enduring literary journals to date in the Caribbean (Kyk-Over-Al).

Carifesta X in Guyana brings these images together through the Robin Dobru poem quoted above and two anthologies of literature. One is already in the archives while the other is now being printed, and they both include this poem within their pages. What is more, they are both, in the context of their respective times, Janus-headed documents of the past, the contemporary and the future. After the inaugural Carifesta in Georgetown in 1972, AJ Seymour edited an anthology, New Writing in the Caribbean : Carifesta 72, and the literary activities when Guyana hosts the festival again in August 2008 are to include the appearance of yet another collection, An Anthology of Caribbean Poetry for Carifesta X, being compiled by Petamber Persaud.

While they both share the same basic purpose, to be permanent records of the literature represented in the Caribbean Festival of the Arts, neither of them will be exactly that. Seymour’s volume is larger in size and scope, and has the advantage of hindsight. While several of the writers whose work he selected did take part in the festival, the document is of the current and emerging writing of the multi-lingual Caribbean in 1972. According to Seymour, he wanted to “introduce the scope and range of the literary work being created in the wider Caribbean and in Latin America.” The scope of the festival had widened from seeking “to achieve approaches to the evolution of a Caribbean cultural personality on a West Indian model” which “embraced only the English-speaking Caribbean.

The new collection which is expected to be available and in circulation during Carifesta X, will be based on participation in the festival. It is designed to reflect the territories that will be in attendance. Again, not all the writers anthologised will be there, but the selected poems represent writing emerging from these countries. There is a very strong reflection of new and emerging poets and some idea of varieties of verse recently developing across the region. A good example of this is the Creole monologues coming out of Barbados. However, some of the territories have provided samples of poetry which represent the nation, but are not the work of new unestablished poets.

Another literary volume inspired by Carfesta I 1972, is Kaie No 11, August 1973, The Literary Vision of Carifesta 1972. Celeste Dolphin’s Editorial declares it to be a “companion to the Carifesta anthology New Writing in the Caribbean. This is the residual memory of much that stimulated our thought in Carifesta ’72 and will provide a bridge into the future and a reminder of the past, stretching backwards and forwards as the Caribbean moves to the rendezvous promised in 1975 [sic] when the 2nd Caribbean Festival of the Creative Arts is planned to take place.”

Here is where Janus and the Dobru poem returns. These documents all look back to the origins, the inspiration and the aspirations surrounding the meetings of artists in Georgetown in 1966, 1970 and 1972. They also all have much to say about the emerging writing in the multi-lingual Caribbean. That is why the poem Wan is a useful bridge.

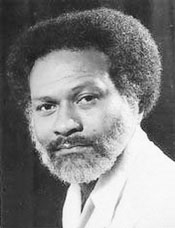

Dobru is an assumed name used by Robin Ravales (Paramaribo, 1935-1983), and means ‘double R.’ During and after 1972 he became the most visible and representative Surinamese poet, whose fame spread across the region largely because of his performances in Carifesta. He was admired for the brand of performance poetry that was rapidly developing in the region in the 1970s and his most popular piece was ik wil iemand haten vandaag (I want to hate somebody today). He also wrote in the national creole language of Suriname, a practice that had also gained much ground in the region at that time.

This poem variously titled Wan or Wan Bon (One Tree) or One, articulates the multi-lingual, multi-ethnic and multi-cultural nature of his native Suriname. But this also happens to be qualities that describe the whole Caribbean region, whose culture(s) Carifesta seeks to showcase. Robin Dobru will not perform in Carifesta X, but his presence will appear in spirit because of his close association with past festivals, his identity, themes and performance tradition.

It is no accident or coincidence that this poem is included in both the first and the most recent anthology of Caribbean poetry for Carifesta.