Gaulbert Sutherland concludes his account of a visit to Arau, an Akawaio-Arecuna

village near the Venezuelan border

The five-foot solar panel, dust covering its face, stood upright in a room at the health centre. It was a gift, but the lack of the appropriate connections to link it to a battery left it unutilized for a number of years. The battery, now discarded, had been connected to another panel elsewhere in the village until it gave out, but the panel at the health centre remained unused.

In another room, there was a microscope that was powered by electricity.

Woken yet again by the cold, I refused to move and stayed in bed until late morning. After the exertions of the previous day, I was surprised that I could blink, even more surprised to find that I could move. The villagers had a meeting which I had wanted to attend, but someone on the way to recovery should rest. I stayed in bed. The weather cooperated for once. It rained. No one was going out that day.

Lunch was noodles mixed with canned tuna, both sourced from Venezuela. Noodles seemed to be a big part of the villagers’ diet. Every home I passed had some noodles and I ate noodles almost every day.

About noon, feeling somewhat bored as the day brightened, I visited the lone school, a ramshackle wooden building with a zinc roof, broken windows, and poles propping up the centre-beam. Officially commissioned in 2000, it was built by villagers with the project funded by Simap. Previously the village had had a school with a thatched roof.

The Arau Primary School had 24 students in classes ranging from Grades One to Nine. Blasin Lewis was the headmaster and the lone trained teacher. He was assigned to the school in 2005. With tired gestures, he said that he was having problems with the National Assessments for Grades Two and Four. The English (Reading) papers came late and they were not sufficient for the number of students sitting the exam. It was postponed as he sought guidance from the education authorities in the region. He said that this was a chronic problem.

A 2007 calendar hung in the corner of the one-classroom school. Two poles, recently placed, stood opposite each other, along the sagging cross-beam of the roof, supporting it. The broken windows allowed the strong breeze to blow right inside and when it rained, the water came in. Outside, another pole was pushed up against a corner of the building supporting it, and at another point the concrete foundation was tipped to one side. This was a big source of worry for the villagers as they were afraid that it would fall down.

“You must put this school in the news so that somebody… the Prime Minister could do something about it.” This statement was delivered with a sad laugh. I had been about to suggest something else but it was obvious from the way it was said that the people placed their hopes of a new school on the Prime Minister.

Apart from Lewis, there was one other teacher and she was employed by the village. Her salary: six grams of gold per month. With pride, it was stated that two other teachers were in training.

Lewis was not a native of the village and related that he had arrived there to teach in September 2005. He recalled that Christmas that year he had gone on a memorable fishing trip on the Arau River and the villagers had caught a lot of fish. It was the last fishing trip there. Shortly after, he said, the river got “bad.”

He also expressed concern about the fact that there were no living quarters for teachers who were not from the village. The villagers had built a little house for him when he arrived and it was there that he lived with his family.

Later in the afternoon, feeling recharged, I nevertheless made a somewhat puzzling decision considering the previous days’ experiences. I said that I wanted to climb Pegall. Maybe it was because that mountain just grabbed me when I first saw it. It issued a challenge, ‘conquer me’ and in a foolhardy, spur-of-the-moment decision I was going to conquer.

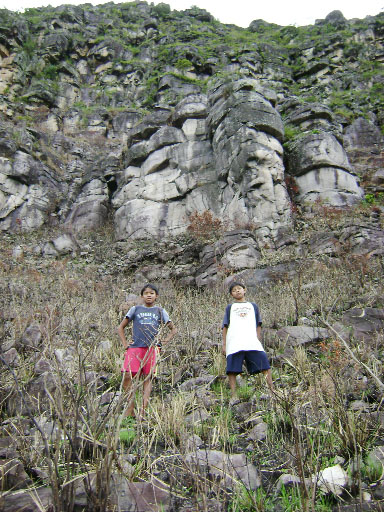

My guides were two of the Chief’s relatives, Ricardo and Derwin, who nimble as ever, raced ahead. I was lucky. There had been a fire that had burned out most of the vegetation from a part of the mountain. It must have been an awesome sight as the mountain burned. I knew that we would not have reached the top because you had to go through a different path, whose pitfalls during the rainy season I was briefed about. There were also portions where you had to balance on a tiny ledge and I had no desire to experience that. Nevertheless, the lower half of the Pegall, which had appeared to be gently sloping soon showed its true nature.

As we climbed higher and higher over rocks while pulling at shrubs, it became steeper and steeper. Maddeningly, my two guides bounced ahead while I sweated and slowed down. At various points, they stopped and waited but as soon as I neared, they bounced up and off they went again. At various parts, there were strange plants and we eventually reached the part where clouds linger. Luckily there was none there at the time.

Thereafter, with the real purpose of taking photos but also with the knowledge that by doing so I would be able to catch my breath, I stopped to admire the view. Many photos taken the preceding day were discarded as the camera ran out of space.

After over half an hour of climbing, we reached the place where the upper segment of the mountain begins to rise up into the sky. From that height, the village looked like a miniature hamlet, while new vistas, not visible from the ground, were unveiled. If one looked very, very closely at the soaring rocks, one could almost imagine that a huge face was staring back.

Off in the distance was a cone-shaped mountain, which the Chief of the Village had said was the sacred mountain of the Akawaios. He had told me that there was a cave high up within that mountain, which was only accessible by ladder. In the past, he said, whenever the Akawaios warred with other tribes, they would go up to the cave and pull up the ladder so their enemies could not follow them. He had made it clear that I or any stranger, for that matter, would not be allowed to enter the cave; it was sacred to the Akawaios.

While staring up towards the top of the mountain, I mused that it was a long way to fall. The Chief had told me about the villager who had fallen from the top and miraculously suffered no broken bones. It was several years ago and the Chief said the man had been taken to the Georgetown Public Hospital, where he spent some time. He said that the man now lived in Venezuela.

Being located where it is, the Venezuelan influence is strong in Arau. Food, clothing and other goods were obtained from Venezuela. Residents knew the Spanish language and many had spent some time in the neighbouring country or had relatives there. Pegall Mountain, which I was on, is depicted on Venezuelan calendars that hung in at least one home. When I had first seen the calendar, I was taken aback. I wondered how it could be that the Venezuelans could print calendars with images of Guyana’s locations and Guyana had not done so.

There were rainclouds to the west so I decided to descend the mountain. We went slowly. Derwin stayed close to me this time. As we moved down, he pointed out some deer tracks. There is a thick little ‘island’ of bush at the side of the mountain where deer lived. Apart from strange lizards, Derwin also found a bird’s nest with two eggs inside. He asked me if I wanted to see the eggs but having heard the birds don’t return when you trouble their nests I said no. He assured me that the bird would return so I agreed to allow him to part the leaves covering the nest.

Ricardo had raced ahead and had arrived at the foot of the mountain long before us.

After I returned, I remembered to put a piece of wood to block the door so that I would not be locked out, as had happened on the first day. I had learned my lesson.

Bigge Irie’s ‘Nah goin home’ blasted out as I visited the home of a villager in the evening. He had put on his generator and was playing music on his DVD player. A number of villagers gathered to watch. More noodles. I spoke to some of the villagers.

They told me of finding large amounts of mercury in the river at the mines. While not generally knowledgeable about its effects, they knew that it could be harmful. They promised to show me some that they had gathered the next day. As the evening went on it grew colder. I left.

‘Nah goin home’ was probably foretelling what was going to happen but in a slightly different circumstance. The turtle confirmed it. It was an ordinary land-turtle. I wish I had never met it.