For almost fifty years Arif Ali has immersed himself in the business of print media. That was not why he left Guyana for London on August 12th, 1957. He went there to study economics and, as he put it, “married an English girl instead.”

Afterwards, he settled for various less intellectually demanding pursuits, first, as a porter in a hospital mortuary then as a bus driver. By 1963, when he had enough money he started a grocery in Tottenham Lane, a heavily West Indian populated area of North London.

The grocery helped to connect him with the Caribbean community. It was, he says, “a typical West Indian grocery.” Apart from the popular Caribbean foods that it offered, “we ran a thriving ‘box hand’ in much the same way that it is done in Guyana. People who were part of that culture gravitated towards the shop.”

His encounter with the print media also has its origins in his grocery. “In those days we would bring in newspapers from the Caribbean – from Guyana, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados. “The newspapers served to connect West Indians in the diaspora with their respective home territories.”

Arif concedes that his first venture into print media can hardly be described as conventional. “We employed an old Gestetner machine to reproduce articles from the various newspapers, We called it The Westindian, sold it for ‘tuppence’ and, frankly we couldn’t print enough.” It was a less than professional effort but it served its purpose. “People wanted news from the Caribbean and we gave it to them as best we could.”

It was out of this ‘primitive’ effort that Hansib which, Arif says, is now “the largest black publishing company in Europe” was born. Not a great deal in terms of minority publishing preceded Hansib. Arif recalls that during the mid-sixties Claudia Jones, a prominent London-based Trinidadian ran the Westindian Digest. That lasted for two and a half years.

The advent of Hansib marked the start of sustained publication in the United Kingdom of newspapers targeting minority communities. April 1971 saw the publication of the first issue of the Westindian Digest.

“That was a very significant moment for me. Apart from itrs significance to a growing Caribbean community in London it was a labor of love for me personally. I had served as journalist and editor and had helped with the paste up, typesetting and the trimming of the magazine. I couldn’t stop looking at it even though some of our advertisers didn’t think much of the effort.”

Hansib’s first venture into publishing also came at a price. “Some people thought it was rubbish and they said so. I wanted to publish and I continued, losing six thousand pounds in six months. I remember that I couldn’t pay my electricity bill and my power was cut off. Actually, my first efforts as a publisher ruined me financially.”

In the longer term, however, his persistence paid off. Since its establishment Hansib has published more than 150 books and booklets on a bewildering array of subjects. Numbered among Hansib Publications are books by the late President Cheddi Jagan, and Guyanese academics David Dabydeen, Clem Sewcharran, Sir Shridath Ramphal and Frank Birbalsingh.

“Black publishing is now healthy business in the United Kingdom and I doubt that many people would deny that Hansib was among the pioneers of black publishing.”

Arguably, however, it was through his role as a newspaper publisher that Arif Ali became a household name both in the United Kingdom and in the Caribbean. In 1973, Hansib acquired the struggling Westindian World and, somehow, persuaded several Caribbean governments to support it. Later, Hansib ran the Caribbean Times, the Asian Times and the African Times, simultaneously and while, in their infancy, indifferent sales meant that most of the newspapers were distributed outside weekend West Indian dances in London, they got the publisher the attention of the minority communities, the British Government and Carib-bean, African and Asian governments. The 1980s particularly, saw the Caribbean Times insert itself into the political process in the Caribbean, often providing controversial coverage of events in the region and influencing the outlook of the West Indian diaspora. Political leaders at home and their High Commissions in London could hardly ignore what, frequently, was the candid coverage of the politics of the region offered by the Caribbean Times and the Letters To The Editor columns – particularly during the 1980s – tell a revealing story of a tempestuous relationship between Ali and Caribbean governments.

For all the controversy that the Caribbean Times frequently created Ali, somehow, managed to establish and maintain amiable relationships with several Heads of Government. One such relationship was with Forbes Burnham, whose administration, perhaps more than any other, frequently came under the cosh in the Caribbean Times.

Arif says that the Caribbean Times played an invaluable role in helping to define the relationship between the Caribbean and the United Kindom. “The Caribbean Times served several valuable functions. Apart from its role as a voice for Caribbean people in Britain the Caribbean Times also helped West Indians to “understand what was taking on back home. The newspaper also played a role in helping policy makers in London to better understand the Caribbean. Additionally, United Kingdom-based businesses with Caribbean interests came to regard the Caribbran Times as an indispensable advertising medium.”

Arif Ali is no longer in the newspaper business. His understanding of the print media and the importance of books and reading, however, have served both to consolidate Hansib and to broaden its role as a publishing company.

During the course of Carifesta X Hansib launched sixteen books in Georgetown, mounted a permanent display at the National Park and Ali says, “sold six million dollars worth of books for two million dollars.”

He calls it “an investment in reading.” The National Library was also the recipient of several Hansib publications while the publisher also donated several books to serve as prizes for competitions being arranged by the Ministry of Education for Education Month which is being celebrated in September.

Here in Guyana Arif says that he has had time “to contemplate some of the challenges that threaten the intellectual growth of the region. “Some of those problems are related to what appears to be the loss of the reading habit among younger Guyanese, the problems associated with copyright transgression and the need to develop the publishing industry.” On the copyright issue he is blunt. “Copyright transgression has to end and it is the government that must bring an end to it; otherwise, it will destroy the incentive of talented writers.” Here, he believes that Hansib can play a role. “As far as school texts are concerned if the government can secure the permission of the writers and publishers to reprint, Hansib is prepared to supply the books at affordable prices if we are able to sell those quantities being sold by the book pirates. I am prepared to talk with the Ministry of Education about that.”

Then there is the issue of encouraging the growth of the publishing industry. “I beleive that the authorities would do well to encourage the existing small publishing equipment to develop the expertise by ensuring that the right equipment becomes available. In my view publishing by the state is not the correct way to go.”

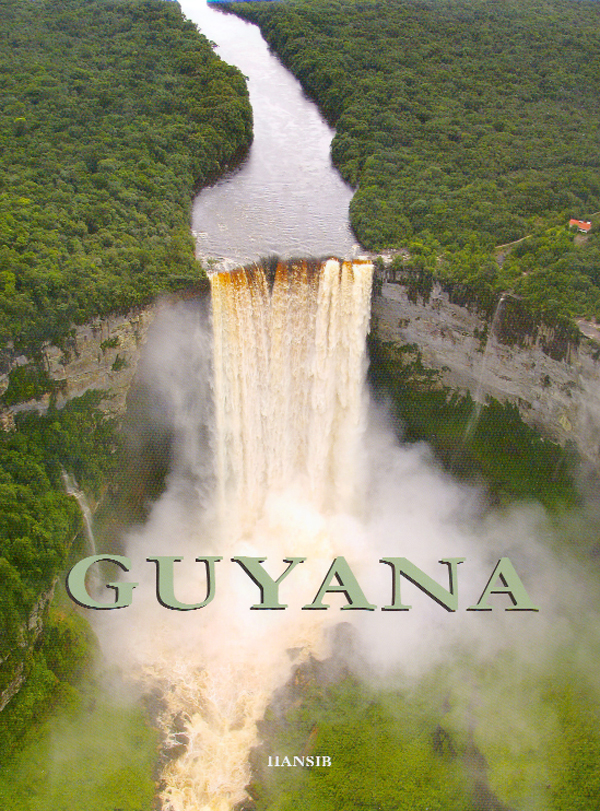

Last year, Ali won the backing of the government for the publication of a prestigious book on Guyana which he says has made a significant impact across the diaspora. He believes that the significance of the “coffee table” publication lies both in its content and in its physical presentation. “I believe that food books can sell a country.

“That is why I am so concerned that Guyana move to a position where writers can have access to the best publishing facilities and where people, children in schools and people who read, generally, can access good, well-presented books at affordable prices. If we can create a strong publishing industry we can restore the culture of reading in Guyana.”