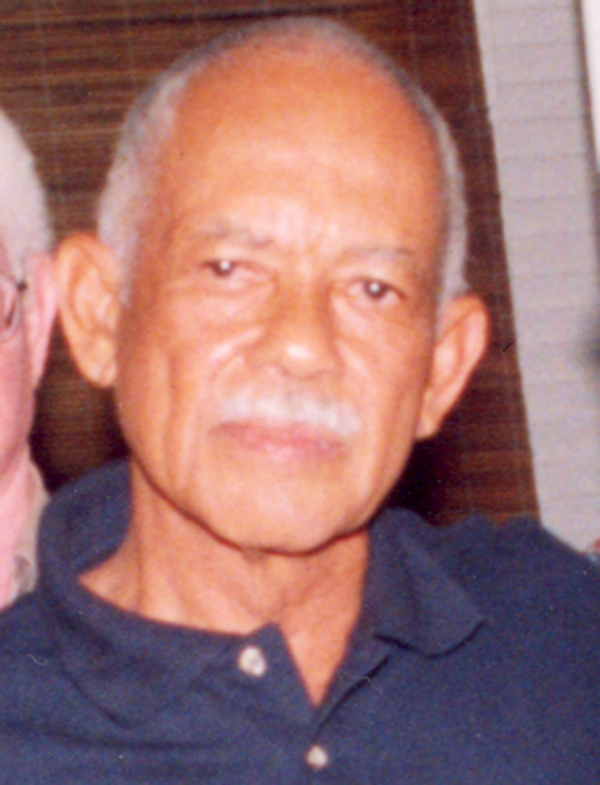

The high artfulness of Hawley Harris

In tribute to Guyanese cartoonist Hawley Harris, who recently passed away, this week we carry an excerpt from a longer essay by Dr. Rupert Roopnaraine.

By Rupert Roopnaraine

Caricatures adorn pharaohs’ friezes and ancient Greek vases. They have been found scratched on the walls of Roman towns, reviling the Christians. They found their way into the carved decorations of the cathedrals and were part of the arsenal in the great theological disputes of the time. It was in the studios of 16th century Italian artists that the 3,000 year-old practice of caricature came into its own as an acknowledged art-form. Caricatura (from the Italian verb caricare: to load, to surcharge) was the name given to the good-natured satirical portraits of friends done by the group of artists working out of the Bologna studios of the Carraci brothers. Annibale Carraci put the case for the seriousness of caricature more than 400 years ago: “Is not the task of the caricaturist exactly the same as that of the classical artist? Both see the lasting truth behind the surface of mere outward appearance. Both try to help nature accomplish its plan. The one may try to visualise the perfect form and to realise it in his work, the other to grasp the perfect deformity, and thus reveal the very essence of a personality. A good caricature, like every work of art, is more true to life than reality itself.”

When Hawley Harris, more than 30 years ago, used his two weeks leave from the Rice Board by turning his hand to cartoons, it neither occurred nor mattered to him that he was taking up an artistic tradition that reached back into the tombs of Egyptian pharaohs. He had imbibed it innocently enough through his childhood comic books, the comic strip being one of the modern forms of the tradition. More crucially, it was for him an assertion of adulthood and independence, a rejection of one way of life and the free choice of another. To earn a living away from the routine and regulation of regular employment, he set aside the things he had been taught by others and took up instead the skills he had taught himself as a child. It was a good base from which to enter the cartooning profession.

When Hawley was a boy of ten, his father would keep him indoors when his friends were playing outside. “He would say you have to pick up your books and read, that sort of thing. But I used to pick up my book and draw and scribble little things. I enjoyed it…I never wanted to be an employee of anybody. My father’s total ambition for me was to get through my Senior Cambridge and then become a Public Servant, go into the Customs or that sort of thing. But that wasn’t for me. I wanted for years to go off on my own.” Harris recalls how he entered the profession: “At that time there was this big conflict between the PPP and the PNC. I was working at the Rice Board. I was about to get two weeks leave and I wanted to go on the Corentyne to spend those two weeks but there was some big political march from Crabwood Creek to George-town and I decided it wouldn’t be safe to be in Corentyne at that time. So staying in town I would draw and draw. I drew something, a comic strip at the start, called Diamond Fever. And I started it. Then my cousin, Rudolph Seymour, who used to do cartooning for the Evening Post, he asked for a piece of it. He said, ‘if you write the stuff, I would draw.’” Harris agreed and for many weeks he wrote the script for Seymour’s drawings. It proved to be so successful an operation that Seymour decided to keep it for himself. Again on his own, with mouths to feed at home, Harris drew a Critchlow cartoon which was accepted by the Chronicle. But as luck would have it, the Chronicle went out of operation two months later.

His inability to hold down a regular job was well known. “Where are you now?” his friends would taunt. “In front of you!” Harris would answer. Eventually he was recruited to the Mirror by Mr. Macdonald Dash, in the course of a session at the Las Vegas nightclub. For Harris, as for other artists and intellectuals of his generation, the city rum shops were communities of wisdom and inspiration, populated by eccentric characters and presided over by a roving band of pavement philosophers: in vino, veritas was the watchword. At the Mirror, he worked under the editorship of Mrs. Janet Jagan until the late President Burnham, who knew a weapon when he felt one, made him an offer which the Mirror could not match and lured him away to the New Nation, where he remained until Mr. David de Caires and the new Stabroek team took him on board the newly launched Stabroek News. “Right away I saw a bit of freedom there. I could do what I liked.”

While the Mirror and New Nation cartoons mostly suffer from the limitation that both were meant to reinforce the editorial argument, the Mirror drawings are clearly stronger, and it has little if anything to do with Harris’ party political sympathies. Comparing the two, an important truth emerges, a law of the genre: cartoons are most effective when drawn against rather than for something. The Mirror cartoons have an energy that derives from their oppositional nature at the time. They attack authority. The New Nation work is derivative and, for long periods, sterile and unimaginative. It enforces authority. In the end, across the sameness and difference, it is the craft we admire in the party political cartoons of the 60s and 70s. But great cartooning, like great writing or great art, is more than craft.

While every cartoonist is a caricaturist, not every caricaturist is a cartoonist. It was not until the 18th century, in the work of William Hogarth, the English painter and engraver, that the ancient art of caricature was turned into a formidable weapon of social and political satire. In Hogarth’s series of prints on various aspects of English 18th century life, especially its dark undersides, the modern political cartoon was born. From Hogarth, through Thomas Rowlandson (inventor of the “speech balloon” of the comic strip) and the venomous James Gillray in England, graphic satire became a force to be reckoned with, feared by Kings, Emperors and lesser tyrants everywhere.

In the new conditions of freedom he found at Stabroek News, Harris entered his golden period. For the last ten years he has treated us to hundreds of cartoons, black lines in white space, extracting humour from the most humourless of situations, going straight to the single simple truth at the heart of some jumbled confusion, provoking us to see and think otherwise.

In Hawley Harris, Guyana has yielded up a cartoonist of the first rank, worthy of his place at the high table, in the company of those who have wielded the pen of righteousness against humbug and injustice. From the turbulence of the early sixties to the uncertainties of the nineties, Harris has pursued his profession with dedication and seriousness, at his best when truest to himself, at no time less than the complete professional.

His accumulated work over the last 30 years stands as an epic achievement, a vivid documentation, in the simplest of forms, of our national and human condition. He told me he was pleased to receive a national honour, because it gave recognition and respectability to cartooning. A modest reply from a modest man.