Cary Fraser teaches race in American history and Caribbean history at the Pennsylvania State Univer-sity. He is also a regular contributor to the Trinidad and Tobago Review.

By Cary Fraser

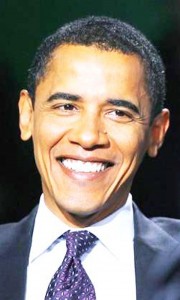

The 2008 American presidential election has reinvigorated the debates about race and democracy in the contemporary world. Should Barack Obama win the election, his victory will force people around the world to focus more attentively upon the issue of how to construct open democratic political systems that can transcend the politics of ethnic/racial mobilization as a cornerstone of governance. Obama’s campaign has been explicitly shaped as a response to the gauntlet thrown down by Martin Luther King, Jr., in his 1963 speech at the Lincoln Memorial:- I have a dream my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. King’s address on August 28, 1963 marked a significant watershed in American politics and history since it offered a vision of human society that embraced a commitment to “all of God’s children – black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Catholics and Protestants – [who] will be able to join hands and to sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last, free at last: thank God Almighty, we are free at last.”

King’s speech had effectively delegitimized the ideology of racial inequality that had disfigured American society for much of its history. In his embrace of racial and religious pluralism, and in his use of the African American rhetoric of freedom and biblical imagery as pathways to America’s transformation into a society cognizant of its diversity, King had effectively moved America into a new world – a world that was being shaped by the post-1945 disintegration of the European colonial empires that had been constructed over the centuries since Columbus’ arrival in the Americas. However, King’s dream of a society that acknowledges equality for all citizens has yet to be fulfilled some four decades after his death, and America’s ability to embrace that vision will be put to the test on November 4, 2008 when voters have to choose between Barack Obama and John McCain as the next President.

For people in the Caribbean, the Obama campaign has posed some very fundamental questions for the future of these societies that share a common history with the United States. The Caribbean societies, like the United States, bear the legacies of (a) European colonial rule, (b) the dispossession and destruction of Native American communities, and, (c) plantation slavery, as formative experiences which continue to define the history and political culture of these societies. For much of the 20th century, the United States has exercised an enormous level of influence upon the Caribbean societies and the 2008 presidential campaign will undoubtedly have an impact upon the current political dispensation in the region.

One potential consequence of the Obama campaign is that it will serve as a catalyst for the political mobilization of disadvantaged communities in various societies. Further, the Democratic campaign to bring more eligible voters into the election by using the internet and voter registration drives, and the sophisticated strategies adopted for using the internet to solicit donations and ideas will have a demonstration effect upon other aspirants for political office in an era where the internet has become an alternative to conventional communication networks. In effect, Obama has shown that the Internet can be effectively used to open the political process to new supporters and to generate funds for candidates. Obama’s campaign in 2008 has also opened the door for these societies to rethink their current political dispensations.

If the United States can evolve beyond the culture of white supremacy and racial majoritarianism that had shaped the society, what would such a development suggest for societies in the Caribbean region that have to confront the challenges of racial, cultural, and, religious pluralism? Obama’s emphasis on a politics of consensus as a strategy of governance and as a symbol of transformative politics – particularly in highly polarized environments – will undoubtedly encourage a reconsideration of the culture of politics within and across the societies in the region.

Just as important, Obama’s status as an “outsider” who has transformed American politics through his campaign has also reinvigorated the democratic appeal of America to the wider international community. In effect, an Obama victory will illustrate the viability of inter-ethnic political coalitions for contemporary societies – a refreshing development that has followed upon the ethnic cleansing as practiced in regions of the former Yugoslavia, genocide in Rwanda, and the threat of fragmentation in successor states in the former Ottoman empire.

For a society like Guyana which has suffered from an extended period of racial polarization and precipitous economic decline – as well as an inter-generational migration of skilled population, Obama’s campaign has offered a political vision and a political strategy that may help to reverse the damaging consequences of the crisis of governance that has afflicted Guyana since the 1950s.