Radicals regarded it as their ritual duty to yell “Limey go home” on encountering British soldiers in British Guiana in October 1953, fifty-five years ago. Under the governorship of Sir Alfred Savage, the soldiers were reviled as invaders. But the regiments were replenished and replaced almost continuously up to and beyond independence in 1966. By that time, they came to be seen by some as saviours.

A decade after the troops’ arrival, the premier Dr Cheddi Jagan wrote a long letter to the governor Sir Ralph Grey in June 1963 asking for them to be deployed on the street. “It is my definite impression that the very presence of the British Army is likely to have a sobering effect on those who are determined to act as hooligans and barbarians, injure and maim innocent people, start racial warfare, pose a serious threat to law and order and overthrow the constitutionally elected government,” the premier pleaded. Perceptions had certainly changed from 1953 to 1963.

A decade after the troops’ arrival, the premier Dr Cheddi Jagan wrote a long letter to the governor Sir Ralph Grey in June 1963 asking for them to be deployed on the street. “It is my definite impression that the very presence of the British Army is likely to have a sobering effect on those who are determined to act as hooligans and barbarians, injure and maim innocent people, start racial warfare, pose a serious threat to law and order and overthrow the constitutionally elected government,” the premier pleaded. Perceptions had certainly changed from 1953 to 1963.

The garrison state

The 1950s were dangerous times. Weakened by the Second World War, Great Britain had to cope with the huge loss of India and other parts of its eastern empire; the Cold War confrontation with the USSR in Central Europe; the waging of the Korean War in East Asia; and the eruption of riots, rebellions and terrorism in its Mediterranean, Middle East, African and Caribbean territories. Trying to avert impending imperial implosion, the British army was stretched to its limits.

The 1950s were dangerous times. Weakened by the Second World War, Great Britain had to cope with the huge loss of India and other parts of its eastern empire; the Cold War confrontation with the USSR in Central Europe; the waging of the Korean War in East Asia; and the eruption of riots, rebellions and terrorism in its Mediterranean, Middle East, African and Caribbean territories. Trying to avert impending imperial implosion, the British army was stretched to its limits.

In this situation, the broadcast by British Guiana’s Governor Sir Alfred Savage on Radio Demerara on October 9, 1953 announcing, “At this moment the Navy and Army are here in sufficient force to cope with any emergency that may arise and the forces are widely distributed throughout the country” was the first that most Guianese heard about the arrival of British troops. At the time they landed, the situation was peaceful.

Military intervention had been undertaken to maintain public order and enforce the imposition of a state of emergency, the suspension of the constitution and the expulsion of People’s Progressive Party ministers from the Executive Council.

Political explanations for these actions are given aplenty elsewhere. But, as far as arrangements for military operations were concerned, British authorities would quickly discover that Guiana was ill-prepared to garrison a large foreign military force for a long period of time.

British infantry regiments ready for rapid deployment to regional troublespots were usually stationed under the Commander, Caribbean Area in Jamaica. At first, units sent to British Guiana were dependent on irregular and unreliable maritime transport for supplies, spare parts, stationery and other stores from that far away island. Further, this country’s shallow river estuaries and muddy shoreline inhibited the entry of very large ships making it necessary for vehicles and stores to be transshipped in Trinidad’s harbours.

Battalions were normally stationed at the war-time US airbase at Atkinson Field, but adequate or appropriate accommodation elsewhere was scarce. Government buildings had to be vacated for use as headquarters offices; the Mariners’ Club, a hostel for merchant seamen, was used as the officers’ mess; and troops could find themselves billeted in hotels not of high repute. In rural areas, cottage hospitals and buildings on sugar estates had to be made available. The Public Works Department laboured day and night to build four new barracks on Camp Road in Eve Leary (now the Guyana Police Force Training School) exclusively for British troops. The governor named them ‘Balaclava Barracks’ at the formal opening on September 20, 1954.

On the social side, the British army’s presence had striking consequences. In the early days, accommodation had to be found in hotels, guest-houses and private houses for families who accompanied troops on lengthy overseas tours of duty. Later, the tours were shortened to obviate such costly accompaniment. In addition, the influx of large numbers of single, young, white males into a colonial society had predictable consequences. Returning flights to the UK usually had to accommodate dozens of local brides! Apart from the loss of young women, the British army expended considerable energy on the recruitment of single, young, male Guianese.

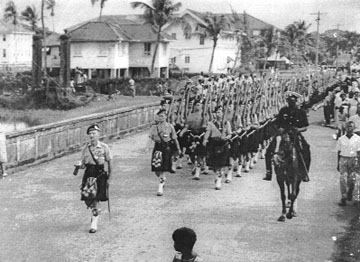

Conspicuous in their quaint kilts and marching to the legato music of bagpipes, the highland regiments were a popular urban spectacle. Parades such as the Remembrance Day and Queen’s Birthday observances; changing-of-the-guard ceremonies at Government House (the Governor’s residence); highland games; and military tattoos always attracted curious crowds and contributed to the regiments’ hearts-and-minds campaigns.

A special legal framework was crafted. Orders-in-council were made, “In respect of anything done or omitted by any member of Her Majesty’s Armed Forces in the course of giving assistance to the civil authorities in British Guiana,” to shield soldiers from being proceeded against in local courts.

States of emergency

On the security side, the maintenance of public order was still the main military mission. In response to the suspension of the constitution, a civil disobedience campaign was launched. This was marked by breaches of the emergency regulations and acts of sacrilege and sabotage. For example, in observance of ‘Empire Day’ 1954, the statue of Queen Victoria outside the Supreme Court was blasted with dynamite.

The 1st Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers had been the first to land. They sailed into Georgetown on board two frigates on October 8, 1953 but, after a fortnight, they handed over to the 1st Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, who arrived on October 21, 1953. In October of the following year, the 2nd Battalion, Royal Highland Regiment (Black Watch) relieved the Argylls and, in turn, were relieved by the 1stBattalion, Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. Next came the 1st Battalion, Worcestershire Regiment, which is remembered for its alliance with the British Guiana Volunteer Force, an event celebrated with a parade in January 1960.

With the return of representative government after the August 1957 elections, the civil disobedience campaign was called off and calm returned. This spell was broken after the August 1961 elections. Certain fiscal measures introduced in the 1962 budget led to widespread dissatisfaction. The British Guiana Trades Union Council (BGTUC) called a general strike during which rioting erupted in Georgetown’s central business district on February 16, 1962 and much property was destroyed. In response, the 1st Battalion, Royal Hampshire Regiment, was called in from Jamaica. Soon afterwards, the 1stBattalion, East Anglian Regiment (Royal Norfolk and Suffolk), also arrived. It was followed by a company of the 1st Battalion, Duke of Edinburgh’s Royal Regiment.

The administration introduced another version of the Labour Relations Bill in April 1963 in the House of Assembly. This was opposed by the BGTUC, which called another general strike. Disorder broke out to be quelled by the 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards, which had relieved the East Anglian Regiment. For the most part, the British Guiana Police Force riot squad dispersed gangs of rioters in urban areas but the Coldstream Guards were required to patrol rural areas where some encounters were fatal. One patrol, under a subaltern fired at a mob, killing three persons and wounding another. During the BGTUC’s 80-day general strike, the 1st/2nd Battalion, Green Jackets (43rd and 52nd), and the 2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards, also performed peacekeeping duties.

Civil violence worsened in 1964 after the PPP called a “Hurricane of Protest” against the British government’s decision to alter the electoral system and to hold fresh elections before independence. The Guiana Agricultural Workers Union (GAWU) also called a strike in the sugar belt ostensibly to protest the British Guiana Sugar Producers Association’s refusal to recognise the union as the bargaining agent for workers. This strike was accompanied by arson, murder and sabotage.

The 1st Battalion, Queen’s Own Buffs, the Royal Kent Regiment, arrived in March 1964 to relieve the Grenadier Guards in maintaining public order. But the disturbances escalated and the 1st Battalion, Devonshire and Dorset Regiment, was brought in after a state of emergency was declared on May 22. The unit’s first mission was to restore order in the aftermath of the Wismar atrocity where it joined a company of Queen’s Own Buffs. In the wake of the Son Chapman launch atrocity at Hurudaia, 43 (Lloyds Company) Battery of the Royal Artillery was sent out in the infantry role to prevent a deterioration of the situation.

The GAWU strike was called off in July 1964 and normalcy returned slowly allowing elections to be held on December 7, 1964. That month, the 1st Battalion, King’s Own Royal Border Regiment arrived.

An independent state

During the dangerous days of the ‘Disturbances,’ the efficient presence of trained British troops in sufficiently large numbers and equipped with superior weapons, communication and transportation usually had a ‘sobering effect’ on terrorists. Troops were effective in containing the wave of criminal violence and restoring normalcy by the end of 1964.

The 1st Battalion, King’s Manchester and Liverpool Regiment and the 1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers, then arrived in January 1965 and were relieved by the 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment, which remained until February 1966. In March, the 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment (Duke of Cambridge’s Own), arrived. This battalion had the historic responsibility of lowering Great Britain’s union flag on the night of 25-26 May when British Guiana gained its independence and took the name of Guyana. The Middlesex Regiment stayed on to work alongside the Guyana Defence Force, departing in October 1966.

For thirteen years between October 1953 and October 1966, battalions drawn from eighteen British regiments, in addition to several smaller support and service units, had been stationed in British Guiana. If, at the start of the troubles in 1953, it was felt that sending British troops to enforce the suspension of the constitution was unjust and unnecessary, it is arguable that, in the end, their peacekeeping role in preventing the disintegration of the country was indispensable to Guyana’s independence.