By Peter Fraser

James started as a creative writer; here I shall concentrate on the literary stage of his career which ended in 1936 with his play Toussaint L’Ouverture, his history of the Haitian Revolution, The Black Jacobins, concentrating on its qualities as a work of history, and then the three works that might be described as cultural studies: American Civilization, Mariners, Renegades and Castaways, and Beyond A Boundary. By comment consent The Black Jacobins and Beyond A Boundary are his best works-you will find no dissent from that here. American Civilization might seem an odd choice because it was published after his death in the incomplete form left by James-it marks James’ move towards writing for a wider audience with his ideology unobtrusively underpinning the work and is thus the stepping stone to Beyond A Boundary. The more political works will be treated in the third and fourth articles. Such a division after the play is somewhat arbitrary: to use the title of Paul Buhle’s biography James was the artist as revolutionary. In this section, however, we are dealing with the works that can be read and enjoyed by those uninterested in or even violently opposed to James’ ideology or politics. What readers get from and writers intend by their works often diverge sharply. There is no law, to invoke a favourite term of James, whether divine, human or historical, that suggests that there is only one possible interpretation of a piece of writing. There is no attempt here, however, to produce a James without the politics. The short stories and novel were finished before he wrote The Life of Captain Cipriani (1932) and from 1932 onwards politics dominates what he wrote. Even in the short stories and Minty Alley we can clearly see James’ radicalism.

The stories and the novel

The five short stories are a mixed bag- ‘The Star that would not shine’ and ‘Revolution’ are really extended anecdotes. The first is about a boy from Trinidad who might have become a child star in Hollywood but refuses to leave home: his family’s dream of prosperity remains unfulfilled. ‘Revolution’ has a Venezuelan tell of the vicissitudes of politics in his homeland where “revolutionaries” with no object other than to seize power battle each other. ‘La Divina Pastora’ is a story with a twist but interestingly hinges on folk beliefs as well as the economic insecurity of women. ‘Turner’s Prosperity’ and ‘Triumph’ are the ones that stand out. Both describe people living economically precarious lives. Turner, a clerk in a shop, owes many creditors and concocts a scheme to get himself out of debt with predictable consequences. ‘Triumph’ is about the lives of women, all teetering on the brink of poverty, living in a yard. Such socially marginal characters as the subject of fiction caused a scandal. Three decades later younger West Indian writers faced much the same reaction-in this as in so many aspects of his life James was one of the pioneers. James handles his cast of characters superbly and sympathetically. This ability would remain a characteristic of his work and only fail him in his attempt at playwriting. In all the stories there is no economic security for the characters-in ‘Revolution’ about a Venezuelan there is no political stability either.

In Minty Alley the focus is the social education of a middle class young man, Haynes. Like ‘Triumph’ its style is social realist-the typical approach of West Indian writers, the only consistent exceptions until very recently being Edgar Mittelholzer and especially Wilson Harris. The extremely unkind might suggest that James reserved any urge to fantasy for his ideological writings. On the other hand if we compare Trinidad and Guyana the cynical might wonder why Guyana in contrast to Trinidad has been blessed with Marxism of a stultifyingly dull sort and non-realist writers.

Haynes, a rather hopeless character, after his mother’s death has to rent his own house to supplement his low wages at the only bookshop in town. His servant, Ella, suggests this course and finds a room for him at 2 Minty Alley. There he lodges with a lower-middle class family. He lives in an extension to the back of the main building opposite the detached kitchen-he does not live in a yard like the one in ‘Triumph’. A middle-aged lady, Miss Atwell, lives in the other room of the extension and most of the other characters live in the main part of the house. Haynes observes the lives of the other people and becomes involved with Maisie a young woman who is related to the house owner, Mrs Rouse. She has a small business making cakes and has problems with her man Benoit. Nothing much, outside of the affair, happens to Haynes. The main focus of the novel is the lives of the main characters living or working in the house, including a nurse always called Nurse Jackson. The main story is the triangular relationship of Mrs Rouse, Benoit and Nurse Jackson. When Nurse Jackson takes Benoit away from Mrs Rouse 2 Minty Alley begins to unravel; Benoit and the nurse soon part and he falls ill. Maisie spreads malicious gossip and forces Mrs Rouse to get rid of Philomen her surviving domestic. Mrs Rouse’s attempt to get married to a retired police sergeant is simultaneously sabotaged by Maisie and abandoned by Mrs Rouse herself with Benoit’s attempted return to the house. Maisie emigrates, it seems, to the USA, Nurse Jackson is found guilty of theft, Benoit dies, Mrs Rouse sells up her house and the novel ends with Haynes taking a last look at the house, now a respectable middle-class dwelling.

Haynes, a rather hopeless character, after his mother’s death has to rent his own house to supplement his low wages at the only bookshop in town. His servant, Ella, suggests this course and finds a room for him at 2 Minty Alley. There he lodges with a lower-middle class family. He lives in an extension to the back of the main building opposite the detached kitchen-he does not live in a yard like the one in ‘Triumph’. A middle-aged lady, Miss Atwell, lives in the other room of the extension and most of the other characters live in the main part of the house. Haynes observes the lives of the other people and becomes involved with Maisie a young woman who is related to the house owner, Mrs Rouse. She has a small business making cakes and has problems with her man Benoit. Nothing much, outside of the affair, happens to Haynes. The main focus of the novel is the lives of the main characters living or working in the house, including a nurse always called Nurse Jackson. The main story is the triangular relationship of Mrs Rouse, Benoit and Nurse Jackson. When Nurse Jackson takes Benoit away from Mrs Rouse 2 Minty Alley begins to unravel; Benoit and the nurse soon part and he falls ill. Maisie spreads malicious gossip and forces Mrs Rouse to get rid of Philomen her surviving domestic. Mrs Rouse’s attempt to get married to a retired police sergeant is simultaneously sabotaged by Maisie and abandoned by Mrs Rouse herself with Benoit’s attempted return to the house. Maisie emigrates, it seems, to the USA, Nurse Jackson is found guilty of theft, Benoit dies, Mrs Rouse sells up her house and the novel ends with Haynes taking a last look at the house, now a respectable middle-class dwelling.

The overlapping and reinforcing influences of class, colour, ethnic group and gender are central to the story. Everyone at 2 Minty Alley lives a precarious economic life: the death of Haynes’ mother sends him there, Mrs Rouse who had once with Benoit enjoyed prosperity now runs an indebted business in a heavily mortgaged house, Miss Atwell hides in her room because her man has stopped giving her money and eventually has to work twelve hours a day in a shirt factory, servants lose their jobs casually. Mrs Rouse is brown and Benoit black: after Mrs Rouse’s husband, presumably brown, leaves with his new lover for the USA and she forms a relationship with Benoit her mother never speaks to her again. The fair Nurse Jackson starts out by having a stronger position than the others but downward social mobility does for her in the end. Haynes himself has not enough drive to be a doctor or a lawyer, the escape routes for a well-educated black man. Philomen, who is East Indian, gets expelled due to Maisie’s racism meshing with Mrs Rouse’s own prejudices-Benoit, she states, being half Indian, was destined to be treacherous. In fact Philomen is perhaps the only person faithful to Mrs Rouse; Benoit is a womaniser who maltreats women-the other men treat women much as he does.

James himself thought the novel was an apprentice work; one of his close London friends of the 1930s decades later expressed surprise that it was published. It needed much more work and had he any inclination to revise it would have been more like his short stories. Paradoxically had it been revised it would now appear dated: its rough edges give it a contemporary feel that the stories do not possess. As well as its interest in race and class it introduces a figure that would appear again and again in James’ ideological works-the ineffectual middle class person, often an intellectual, who suffers from being outside of the struggle of the working classes. The working classes, however, hardly feature in the novel and usually receive short shrift. The novels and the short stories had all been written before his arrival in England in 1932.

James himself thought the novel was an apprentice work; one of his close London friends of the 1930s decades later expressed surprise that it was published. It needed much more work and had he any inclination to revise it would have been more like his short stories. Paradoxically had it been revised it would now appear dated: its rough edges give it a contemporary feel that the stories do not possess. As well as its interest in race and class it introduces a figure that would appear again and again in James’ ideological works-the ineffectual middle class person, often an intellectual, who suffers from being outside of the struggle of the working classes. The working classes, however, hardly feature in the novel and usually receive short shrift. The novels and the short stories had all been written before his arrival in England in 1932.

The play

James’ last literary work would be a play. An off-shoot of his research into the Haitian Revolution James in 1935 solicited Paul Robeson, the great American singer and actor and orthodox Communist, to play the lead role. Robeson was then living in England and in 1936 Toussaint L’Ouverture was performed with him in the lead. James’ last literary effort was not a success. It tries to cover much the same ground as The Black Jacobins moving from just before the start of the Haitian Revolution to Dessalines’ declaration of independence. It is full of exposition and explanation, but has little dramatic tension. The large cast of characters deployed in the play does not work as effectively as it did in ‘Triumph’ and Minty Alley. It was the last effort of James the artist though he did revise it in collaboration with Dexter Lyndersand in the 1960s and it was performed in Nigeria and Britain. Reviewers of the original had not been impressed; about the revision Arnold Wesker, the radical English playwright who was sympathetic to James’ politics wrote to James himself: “there is a spark… missing from the whole work…there does seem to be something wooden about the play. The construction is dramatic; the dialogue carries the story and the dialectic of what you want to say, but when all the component parts are put together, it doesn’t work.” James’ strengths lay in short stories and the novel-one might regret losing the other works that might have appeared but be totally unmoved by losing any other plays.

The Black Jacobins

James as he explained wrote The Black Jacobins to demonstrate the capacity of Africans to rule themselves. A reader unaware of or uninterested in his motives will discover what remains the most interesting introduction to the Haitian Revolu-tion. It is a work that combines analysis and narrative very well, sets out the economic and social bases of the revolution and demonstrates the interconnections between events in Haiti and France. James starts by analysing the structures of St.Domingue, the basis of which was the labour of the enslaved. He sets out clearly the divisions within slave society-between the creole slaves and the newly imported ones; and the complexity of free society. This was divided into the elite whites, the royal bureaucracy and military and the big plantation owners-the interests of these did not always coincide; the other whites-again not a homogeneous grouping as it varied from merchants to artisans; the free coloureds and blacks-some of whom could be owners of large properties and slaves but a group with limited rights. The rapid economic development of St. Domingue introduced large numbers of African-born slaves, people not long accustomed to slavery like those born into slavery. This rapid economic development widened the breaches between the royal establishment and the planters and merchants because the French economy was neither able to supply St. Domingue with all its needs nor to be its most lucrative market. With the outbreak of the French Revolution the differences between the royal establishment and other groups widened: the divisions in white society became more pronounced; the free people of colour demanded their rights; the granting of these rights exacerbated the tensions between whites and free people of colour; and the ending of slavery drove this process towards revolution.

The main narrative begins as the revolution in France and Haiti becomes more radical. Toussaint becomes the central character as he moves towards and achieves military and political leadership. Toussaint is central to the defeat of the British attempt to conquer St.Domingue. He tries to rebuild the island by maintaining the link with France but as the Jacobins, the most radical revolutionaries, fall from power and are replaced by the Directory and then Napoleon the revolutionary commitment to freedom for the slaves disappears and Napoleon sends an expedition to restore French rule and slavery. Toussaint is deceived and imprisoned in France-Dessalines assumes command and defeats the French and proclaims independence in 1804, less than a year after Toussaint’s death in France. James had been struck by what a good story it was even before he left Trinidad; reading the scholarly accounts and the archival sources reinforced that impression and his literary abilities enhance the telling. It is not a work without flaws.

The main narrative begins as the revolution in France and Haiti becomes more radical. Toussaint becomes the central character as he moves towards and achieves military and political leadership. Toussaint is central to the defeat of the British attempt to conquer St.Domingue. He tries to rebuild the island by maintaining the link with France but as the Jacobins, the most radical revolutionaries, fall from power and are replaced by the Directory and then Napoleon the revolutionary commitment to freedom for the slaves disappears and Napoleon sends an expedition to restore French rule and slavery. Toussaint is deceived and imprisoned in France-Dessalines assumes command and defeats the French and proclaims independence in 1804, less than a year after Toussaint’s death in France. James had been struck by what a good story it was even before he left Trinidad; reading the scholarly accounts and the archival sources reinforced that impression and his literary abilities enhance the telling. It is not a work without flaws.

James was determined to show that West Indians (and Africans) were modern people, able to rule themselves in the modern world. Modernity was equated with European (and American) developments and beliefs: hence though there are hints in The Black Jacobins about the role that the slaves’ African cultural heritage played in the Haitian Revolution they are no more than hints. In this James was much the child of his age. James’ emphasis on individuals, here on Toussaint, leaves other characters somewhat obscure. There is more than a little truth in the early Trinidadian response to the Cipriani biography that James fell easily into hero-worship. Several of the other leaders of the revolution appear to think much the same as Toussaint about the need for a continuing connection with France to enable Haiti to prosper; even Dessalines, whom James sees as most perceptive about French intentions did not want a break with the modern world. All these leaders felt and acted on the belief that the ex-slaves would need to work on the plantations. In that respect as military men, like the military aristocracies of Prussia and Japan, their concern was economic development for national defence. One might note that the forced industrialisation of the Soviet Union under Stalin was directed to the same ends. A more subtle influence is also at work. James wanted to see the Haitian Revolution following the pattern of the French and Russian Revolutions-hence the name of the book and the references comparing Toussaint unfavourably to Lenin. The American Revolution, with its paradoxes and limitations, might have been the better analogy. Its aim was originally to obtain the political rights of Englishmen for the American colonists, it ended with their independence. It replaced one lot of landlords with another; its leaders’ hesitations in the face of slavery and their willingness to remain part of the international economy have important parallels with the Haitian leaders’ attitudes; in both revolutions regional differences play a large part as they did after independence. One can see why Trotsky (whose history of the Russian Revolution is still worth reading and suffers from similar defects) felt that James sometimes forced characters and events to fit certain moulds. Despite all this and his intention to write a book to help liberate Africa(it closes with the words of a 1935 black Rhodesian against colonial rule and a prediction about the long road to African freedom) like Trotsky, James with The Black Jacobins wrote an historical work of enduring importance.

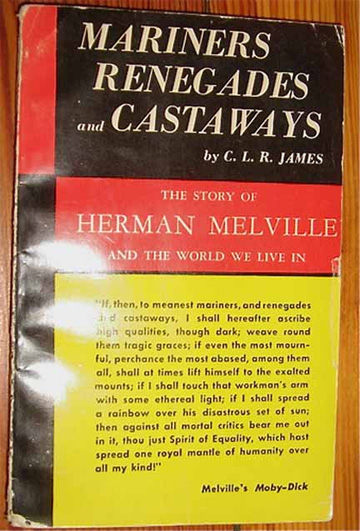

Mariners Renegades

and Castaways

In Mariners, Renegades and Castaways James analyses Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick carefully and interestingly. It is first of all a technically accomplished work of literary criticism, examining the structure of the novel and the writing. It also tries to link the novel and especially its central character Ahab to the political developments of the first half of the twentieth century. James describes the character of Ahab as foreshadowing the totalitarian leaders of the 1930s and 40s, particularly Hitler and Stalin; so does Ahab’s relationship to the officers and men and their failure to stop him even though they know he will destroy them. He felt also that Melville had most accurately foreseen the political consequences of the development of capitalism. The discussion of the rest of Melville’s writings, which James clearly has no liking for, does not reach the same standards. The expression of James’ obsessions with the failings of non-revolutionary intellectuals is quite weak. The book ends with a chapter where James writes of his period in the USA and his experiences on Ellis Island where he had been detained for overstaying his visa. It is interesting about the conditions and behaviour of fellow inmates. In fact James also uses a fellow inmate, an orthodox Communist, as an awful example of the dangers of Commu-nism. This is James at his very worst: it is impossible to defend this denunciation of someone who had done his best to help other inmates. There is always the possibility that this was fictional to illustrate a point: that orthodox Communists were dangerous and that he James was not one of them. We need to be cautious when reading James about his own life. Memoirs and autobiographies should be distrusted on principle

American Civilization

This interest in telling the story of his life reappears in Beyond A Boundary. Before we discuss that American Civilization needs to be examined. This had been written before the Melville book but was never finished and never published in his life-time. It is an attempt to provide a radical interpretation of the USA for a general audience but also to understand the revolutionary potential of American society. Here my main interest is two aspects of the book: his use of American writers-Melville obviously, and the poet Walt Whitman – to understand American life and his examination of popular forms of entertainment-film, radio shows and the comics to understand what ordinary Americans wanted from life. The first aspect would be developed in Mariners, Renegades and Castaways; the second would be transformed into the study of cricket in the West Indies and England of Beyond A Boundary.

Beyond A Boundary

James loved to tell stories. At its simplest Beyond A Boundary is the story of how the West Indies cricket team got its first black captain, Frank Worrell. It begins with James’ first becoming fascinated by cricket and literature, his discovery of the joy of playing and what the game meant to the people he knew. It provides character sketches of many well-known and some obscure cricketers: Learie Constantine, George Headley and Frank Worrell are perhaps the chief of these. By returning to the West Indies in 1958 and being in the right job to campaign for Worrell to be made captain the book comes to a proper end. In between James has shown the importance of cricket to establishing a West Indian identity; its transformation in England in the 19th century advanced by the extraordinary figure of W.G. Grace and the significance of transformations in British capitalism to this transformation-later he will link the dullness of 1950s cricket to the welfare state; he tries to demonstrate that cricket is an art, unlike other sports and games; it ends with the campaign for the Worrell captaincy. It demonstrates James’ superb knowledge of the techniques of cricket; it shows his ability to delineate character; it is the book that he had wanted American Civilization to be: radical but popular and demonstrating the capacity of ordinary people (‘the masses’) to know what they wanted and to act to achieve their aims. It was a fitting way to end his writing career-for him there would not be another book conceived as a unified work. Here the major themes of his writing come together and are developed.

The book is divided into seven parts. The first, ‘A Window To The World’, deals with James’ family and the values they inculcated in him, his growing fascination with cricket and literature, and his secondary school. Here he stresses Puritanism-he certainly acquired the Puritan work ethic. He was, however, a scholarship boy who rebelled against the conventional path such a boy should take. Yet on leaving school, he taught at his old school and at the Teachers’ Training College, wrote about cricket and was a prominent member of the Beacon group of writers; this work ethic remained a characteristic of his in later years as far as his writing and political work was concerned. In many areas of his personal life this also held true: an American radical tells the story of James being offended when it was suggested that an unauthorised edition of one of his books should be stolen for him. (Perhaps in other respects he was not Puritan-his first wife appears nowhere in these early pages, neither do his second or third wives). He introduces the limitations imposed by class and colour and those on ‘spirit, vision and self-respect’ produced by a British education at the time. His enduring love of Ancient Greece appears. This part ends with his recognising that he has been shaped profoundly by his education in the broadest sense when he understands that his American comrades have very different attitudes to cheating in sport.

The second part ‘All The World’s A Stage’ describes the colour-coding of the cricket clubs and his strange choice to play for Maple (the brown man’s club) rather than Shannon (the black man’s club and the one Constantine played for). Two outstanding portraits of cricketers follow, one of George John, the great fast bowler, the other of Wilton St. Hill, one of the lost great batsmen of cricket. Colour, class and race (and St. Hill himself) acted against the fulfilment of St. Hill’s great talent that ‘had nourished pride and hope…and atoned for a pervading humiliation’ among thousands of Trinidadians.

The centre of the book is ‘One Man In His Time’ about Learie Constantine, the man, the cricketer, the friend and mentor of James. Constantine’s cricketing career is set out and his political views that James at first found too harsh explained. His kindness to James, getting him to England where he helped write Constantine’s Cricket and I and providing him with a place to stay, and later in 1938 with clothes for the trip to the USA, are the substance of this part. Constantine encouraged James to leave Trinidad as James’ politics became more radical and his livelihood (teaching at the Training College) became endangered. In England Constantine introduced James to people in cricket journalism and to ordinary English people. This part is a study of both Constantine himself and James’ political development-Constantine funded the publication of The Life of Captain Cipriani. It was in Nelson that James says he began to prepare his study of the Haitian Revolution. It is the most affectionate portrait in the book and James writes of Constantine with the greatest respect even when their political views had diverged widely, as they had by the 1950s.

‘To Interpose A Little Ease’ is the ironic title of part five. It is short and focuses on George Headley. Partly because he did not know Headley as well as he knew Constantine, and partly because he confesses himself baffled by the phenomenon of a truly great batsman it is the thinnest chapter in the book. Some things defy description and explanation even for a CLR James.

Part five ‘W.G.: Pre-Eminent Victorian’ is the most sustained analysis in the book of the social significance of cricket. It starts by looking at cricket in England before W.G. Grace (before the 1860s) and explains the role of Thomas Arnold (and his populariser Thomas Hughes author of Tom Brown’s Schooldays) in creating the public school value system which is reinforced by cricket. Grace himself to James is one of those people who sums up an era in himself ‘in a complete and perfectly blended way’. Grace becomes for workers in the industrial cities of England a symbol of the pre-industrial world. James derides Trotsky’s attitude that sport distracted workers from politics: in the West Indies he sets out clearly the connection between sport and radical politics but recoiled from the connection with more conservative politics that he suggested here. The connection between styles of cricket and society fascinated James: he sees the Body line tour of 1932 as a product of the violence of the modern world and in the next part links boring cricket in the 1950s to the welfare state depriving cricketers of ambition. More recent historians of cricket have modified James’ analyses but they remain stimulating.

The next part ‘The Art And Practic Art’ contains the chapter on welfare-state cricket but more interestingly has James’ attempt to explain why cricket is an art. As with James’ other excursions into philosophy it cannot be said to have succeeded.

The final part ‘Vox Populi’ recounts the successful campaign to have Frank Worrell made captain of the West Indies. Here the people, so central to James’ political theories, act as he would wish them to do. The book ends with two chapters: the first on returning to Trinidad and his school and family, introducing his American born and bred son to them, the second reflections on Worrell’s famous 1961 tour of Australia. It ends: ‘I caught a glimpse of what had brought a quarter of a million inhabitants of Melbourne into the streets to tell the West Indian cricketers good-bye, a gesture spontaneous and in cricket without precedent, one people speaking to another. Clearing their way with bat and ball, West Indians at that moment had made a public entry into the comity of nations. Thomas Arnold, Thomas Hughes and the old Master would have recognized Frank Worrell as their boy.’

An assessment

The quality of the writing is a remarkable achievement. James’ literary works are worth reading not merely for their place in the history of West Indian literature; The Black Jacobins remains an important work on the Haitian Revolution and it can be studied as an example of how to combine analysis and narrative; Mariners marks an important stage in West Indian literary criticism; the techniques visible in American Civilization are an early example of cultural analysis and find their finished expression in Beyond A Boundary. That book, his masterpiece (though as an historian I have a special affection for The Black Jacobins), defies easy categorisation-part memoir, part study of the aesthetics of sport, part history of cricket, and above all a study of the place of cricket in West Indian history. Here his contribution is not merely to West Indian intellectual history.

What assessment can we make of James as a writer? It is important to remember that no other West Indian has the range of James across genres and none I can think of has written, besides work on the British West Indies, well and in detail about the USA, Britain, Africa and the Caribbean beyond the British territories.

His short stories and the novel show great promise and real achievement. His pioneering focus on the economically marginal in society (a focus shared with the Jamaican Claude McKay and his Trinidadian fellow Beacon member Alfred Mendes whose Black Fauns was published the year before Minty Alley) had caused a scandal but would become normal in West Indian fiction. As Ramchand wrote: “The Trinidad [we can broaden this to West Indian] audience was interested in respectability, not in questions of art.” The second novel that he had hoped to write was never written: from the evidence of the stories and novels this would have been worth waiting for. Instead we were left with the last literary work, the play, which, original or revised, was mediocre. It did at least provide Paul Robeson with a role that was neither Othello nor an African chief. Times change; before the Second World War Robeson had to leave the USA to get proper roles; in recent years Black British actors have had to go to the USA to further their careers.

The Black Jacobins marks the beginning of modern West Indian historical writing. James’ book was the first of three fine studies to appear in the two decades after 1938. In 1944 it was followed by Eric Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery, an interpretation of the effects of slavery on British industrial development as well as an economic explanation for British anti-slavery. This would generate the greatest controversies of any historical work written by a West Indian (there is a third thesis-that slavery created racism). In 1956 Elsa Goveia’s A Study on the Historiography of the British West Indies to the end of the Nineteenth Century was published. This deals with the historical