This essay – The Militia and its Parade Ground – has been extracted from James Rodway’s The Story of Georgetown. Revised from a Series of Articles in the Argosy, 1903. (Georgetown: The Argosy Company Limited, Printers, 1920). This chapter examines some aspects of the British Guiana Militia and the origins of the Parade Ground which has now been renamed Independence Park.

James Rodway (1848-1926) was born and educated in the UK. A botanist by profession, he came to British Guiana in 1870 and was appointed Librarian and Assistant secretary of the Royal Agricultural and Commercial Society and honorary curator of the British Guiana Museum and co-editor of Timehri.

James Rodway

Every male inhabitant of the colony, with very few exceptions, between the age of 16 and 50, was bound to enrol in the Burgher Militia. Whatever his nationality, he could not remain without taking the oath of allegiance.

Before Stabroek was thought of in 1766, Captain Peter Haley of Peter’s Hall was head of the Militia company composed of the white men living on the east side of the river from the sea to Land of Canaan. He was Justice of the Peace, commissary and policeman and virtually the only government official in his district.

With the establishment of a town and a considerable increase of population, the Militia necessarily became of some importance. A parade ground was provided on the site of the Roman Catholic cathedral and regulations were drawn up for drilling at intervals. In 1793, free coloured men were exempted from head taxes on condition that they took part in bush expeditions.

The burghers always claimed that it was not their duty to defend the colony against outside enemies, therefore, we never hear of them when the French or English arrived. Their duty was to keep order − to act as a kind of voluntary police − and to hunt runaway slaves. But, as bush expeditions were hardly agreeable, much of the last duty was done by the free coloured men who, as we have already seen, formed also the fire brigade.

Hunting the Maroons

About 1795, the maroons became very troublesome, even venturing so far as to establish themselves behind Peter’s Hall. But their headquarters were near the sources of the Lamaha from which they made excursions to the East Bank as well as the coast estates.

In 1801, it was resolved to break up their camps. Captain Charles Edmonstone (Waterton’s friend) was therefore authorised to make the attempt with an expedition consisting of a corporal, sergeant, eleven soldiers of the Negro Rangers, a corps of Burgher Militia and sixty Indians. The expedition went up the Madewini creek and marched for eight days towards the Mahaica. Arrived at a wooded sand-hill, Edmonstone, his faithful slave Coffee, and two Indian chiefs being well ahead of the rest of the party, one of the chiefs suddenly spied a maroon, and fired at him.

At once, the party of four was surrounded by a body of runaways, the leader of whom challenged Edmonstone to fight him, at the same time pointing his gun. The captain fired at once and shot his burly challenger dead, on which the whole body of maroons also fired, wounding Edmonstone and killing the two chiefs. The remainder of the party coming up, the negroes fled into the bush. Edmonstone was found senseless with four slugs in his body. On recovering consciousness, he ordered them to let him die but, above all, pursue the runaways. They carried him to Pln. Alliance and he ultimately recovered but only one of the slugs was extracted at that time, another later; two gave him trouble for the remainder of his life.

However, the sturdy captain was undaunted. In 1802, when it was reported that the maroons had extended a line of communication from the back of Stabroek almost to the Loo, he again offered his services with the result that an expedition scoured the sources of the Camouni and Boeraserie Creeks, destroyed the camps and took several prisoners.

Now and then, the bush negroes came to the Sunday market in Stabroek where they escaped observation among the crowd and even went so far as to sell provisions and plot with friendly sympathisers to carry out plantation raids. On Sunday April 20th 1806, the Burgher Militia was called out to surround the market and examine the passes. They discovered nothing, however, probably because, as the Gazette suggested, there was too much parade.

In 1807, Captain Edmonstone again took part in an expedition, which was considered so successful that the Court of Policy granted him, as a token of their sense of the value of his services, a vase costing 100 guineas and freedom from taxes. Seventy negroes were taken at this time and they were offered for sale outside the colony; but there was some difficulty in getting buyers in the islands.

Bringing Home the Trophies

Under the Dutch rule, a hundred guilders was paid for each captured runaway, dead or alive; in the first case, the claim was vouched for by bringing back barbecued right hands. It was not uncommon to see a returning bush expedition marching through Stabroek with several such trophies fixed on the points of their bayonets.

In 1795, a maroon chief was burnt to death in front of the then jail (now Brick Dam Police Station) after he had been tortured with red-hot pincers. When, in 1796, a certain handsome coloured woman named Princess Changuion was condemned to be flogged, burnt in the forehead, and then to have an ear cut off, the newly-arrived British helped her to escape from the same jail. In 1812, rewards for dead runaways were abolished but floggings were still carried on in the same place. This was so distressing to one of the governors that he asked that these punishments should not be inflicted so near the King’s House, after which they were done in the market place.

In connection with the bush expeditions, we may mention that every Burgher had a slave porter to carry his supplies. Many of them started well primed, as is suggested by our sketch, but they were not all so jolly when they returned. In 1807, we find the Court allowing among the expenses of a bush expedition, 1,100 guilders to Dr. C. H. Lloyd for medical attendance, and 825 guilders to Love Ann Jordan for nursing John Hadfield, who was wounded. In 1810, D.P. Simon asked for assistance; he had become sick from fatigue and exposure and was unable to pay his medical attendants. The Court, in consideration of services in the expedition, granted him 550 guilders.

Vindicating their Honour

Militia service was never quite popular. People did not object to be commissioned officers but fines were imposed for refusing to act as corporal. Even the officers had quarrels among themselves, as may be seen from a case in April 1806.

First comes a ‘General Order’ which states that Major Arthur Blair, Commandant of the Demerara Cavalry had declared that he could not in all points obey the orders of his superior the Lieutenant-Colonel Commandant. The Governor, therefore, superseded Blair. This led to a meeting, on the 26th, of the corps, at the Union Coffee House, where they all agreed to send in their resignation to Major Blair, and voted him a sword, value 100 guineas. The superior referred to was Captain Farquhar Macrae, whose death was reported two days later. The Gazette said he was a man highly respected for his private worth, whose loss was a public calamity. He came to his death through a wound received in adjusting an affair of honour with A. Blair, Esq., in consequence of a difference arising out of his appointment as Lieutenant Colonel, improperly agitated at a meeting of the Sons of St. George.

The parties met on Sunday morning at La Penitence and exchanged shots at twelve paces. Macrae fell at the first fire, with the ball in his hip. Every possible attention was immediately afforded; he was carried to the hospitable and friendly mansion of the Hon. A. Meertens, at Rome, where he died next day. “In this most trying situation, the high sense he entertained of honour, which he had vindicated, prevented him from saying who had inflicted the wound.” So said the obituary notice.

Perhaps, some of our descendants a century hence will quote our reports as curiosities, as we do this. The matter was not yet ended for, on the 5th May, a meeting of the officers of the First Battalion and the Rifle Corps was held in the Union Coffee House to consider the cause and merits of the misunderstanding. Macrae was justified, and it was resolved to erect a monument in the shape of a marble pyramid to his memory in the parade ground (near the site of the R.C. Cathedral) and to wear mourning for three months. It does not appear, however, that the monument was ever erected; perhaps it was interdicted.

The Court’s Indignation

In 1807, Mr. James Robertson told his superior officer, Captain Dodgson, when required to attend a court-martial on Captain Osborn for refusing to go with a bush expedition, that the burghers, in his opinion, were not bound to go on such expeditions. He wanted the governor’s opinion and he got it for it was resolved to acquaint Captain Robertson with the Court’s indignation at his disobedience to his superior officers; also, at the disrespectful and improper manner of expressing his opinions, and he was to be reprimanded.

In 1812, during the war with the United States, the mouth of the river was pestered so much with the enemy’s privateers, that it was actually blockaded from the 25th to the 30th September. The inhabitants however, could not stand that; they rose to the occasion. Governor Hugh Lyle Carmichael accepted the offers of Lieutenant Jacobs, Mr. de Munnick and Captain Evans to drive off the enemy. This they did with three small vessels manned with sailors and the Militia. The governor, in speaking of the matter, said he had the most heartfelt gratification in making known the spirit and gallantry of the burghers; they went out to meet the arrogant foe, who fled with precipitation, leaving part of their spoils behind. A similar disposition, he said, pervaded all the inhabitants.

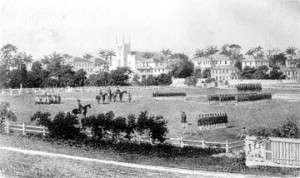

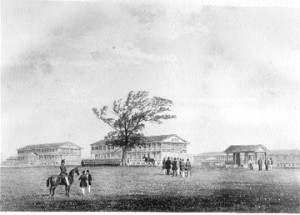

To that energetic governor we owe the present parade ground. On the 20th October 1812, he told the Court that the troops and militia, having no proper place for parade or exercise, he had accepted the offer of Thomas Mewburn, for Thomas Cuming, of a grant of occupancy of 16 lots in Cumingsburg; if thought proper afterwards, these might be secured for a consideration and used for public buildings. He had ordered the place to be converted into a parade ground and would pay the cost from the King’s chest. He concluded his speech by saying, “Demerary, I at present consider my country, and were my ancestors and myself born in it, I should not feel a more cordial and sincere interest in its welfare and prosperity.”

Presentation of Colours

In 1816, a presentation of colours voted by the Court took place. Major Tulloh said: “In handing these colours to you, I presume I need not remark that they are never to be abandoned, but with your lives.” The flag was probably white as the Georgetown battalion was known as that of the White Banner. Inside a laurel wreath, above which was a crown, were the words:

Demerary Militia

First Battalion

Pro aris et focis.

The Militia did well during the East Coast Insurrection of 1823. Martial law was declared, every man without exception called to enrol and an almost unanimous response was made. Business in Georgetown was suspended, the slaves kept indoors; save for the armed citizens and soldiers, no one could be seen. No doubt they thought the whole colony in danger and feared that the results might be similar to those in Berbice in 1763, when the fort and all the plantations had to be abandoned.

At the first alarm, there was a rush for the vessels in the river; ladies jumped from the stelling into boats at the risk of their limbs if not their lives and altogether there was a decided panic. St. Andrew’s church was occupied as quarters by a provisional battalion of exempts and, on one occasion in the absence of the minister, Major Thomas Frankland gave the men an address. Lieutenant Colonel John Croal made himself very conspicuous as did also Major McTurk who imprisoned one of his men in a fowl house on a charge connected with an anonymous letter, for which he was ultimately sentenced to pay damages. After the affair was over, everyone was thanked by the Secretary of State, in the name of the King, for their exemplary zeal, discipline, and good conduct.

By an Order in Council published here on the 22nd of June, 1839, the Militia laws were suspended and it was expected that they never would be revived. The main reason for their existence was the fear of slave revolts; with the Emancipation, the government supposed everything of that sort to be at an end.

The Parade Ground

Before speaking of the revival of the Militia, we have to say something about the parade ground, which was kept up entirely for their use. In 1823, it was the scene of a shocking series of executions in connection with the East Coast insurrection. For several days, at the latter end of August, processions were seen passing every afternoon from the Court House with condemned prisoners to be hanged on the parade ground. At the Fort, a row of grisly heads were fixed on poles and, here and there along the public roads, corpses hung in chains.

There were no Promenade Gardens then, but Middle Street was a walk across the middle of the ground, hence its name. After the Militia laws were suspended, the ground was much neglected and, save for the observatory allowed to be erected thereon, it was nothing better than a wilderness.

In February 1843, it was reported that Mr. Hackett had proposed to the Town Council a plan for converting the parade ground into ornamental public walks: the Gazette did not particularly admire his plan; it was too much of a ‘supper-tray pattern.’ There were to be two temples north and south, reminding them of two giant tea canisters, a barbarism which could not have been expected from Mr. Hackett. They were to be named Victoria and Albert.

Promenade Gardens

In speaking of the New Market in August 1844, the Gazette said that the next place which required the hand of taste was the parade ground. It invited decoration and would well repay labour and expense in the lustre which would radiate from that ancient martial rendezvous, if properly beautified. Without wishing to interfere with the Astronomical Observatory, it was suggested that the greatly needed Government House might be erected on the southern half, while the northern might have a public garden separated from the Government grounds by an iron railing: the beauties of one would enhance those of the other; and in their walks, the citizens might enjoy the pleasure of beholding a fine architectural monument of public taste and spirit, which they had contributed to raise for the abode of their ruler. The most choice of the rich specimens of the vegetation of Guiana might be scattered with admirable effect around or by the sides of the different walks, statues, etc., with which such a scene would be becomingly set-off.

In February 1846, after the beach promenade had been washed away, the matter was again mentioned but it appears there was some legal difficulty on account of the site being granted for a parade ground. A year later, the place was described as a disgrace to a British colony. Why could it not be laid out as a garden? The answer was that money could not be spared. In August 1851, the matter came before the Town Council who had already appointed a committee to inquire into it.

It was then agreed that a public promenade on the parade ground should be established if funds could be procured. It was agreed also that a subscription list be opened and, when $1,000 had been contributed, they would undertake the work. The governor offered $500 at the same time stating that he had not objection to the promenades in the parade ground being under the entire superintendence of the corporation. It was therefore resolved, on the 8th September, to accept the governor’s offer and to contribute a like sum. A Committee of Superintendence was then appointed to effect the necessary arrangements and obtain other subscriptions. In June 1853, it was agreed to send to Trinidad for a person from the Botanical Gardens there to lay out a garden and, in the latter end of that year, Mr. Blank had displays of fireworks on the parade round.

Revival of Militia

After the ‘Angel Gabriel’ riots in 1856, the Militia was revived. Every male inhabitant between the ages of 18 and 50, qualified by possession of real property value $500, a rental of $96 per annum, tenancy of 6 acres, or income of $240, was bound to enrol.

This revival gave trouble from the first. On account of the great increase in qualified persons, everyone was not bound to serve; there was a ballot, and substitutes were allowed. Under the old regulations when all had to serve there was less trouble; now it was felt as a hardship that some should be bound to serve and others quite free.

There was another side to the question: it was a drawback to the clerk when he had to attend drill, perhaps at an inconvenient time for his employer. Possibly, this might sometimes stand in the way of his getting a situation when there was a chance. Again, a Militia man might be detained by business duties, with the result that he could be brought before the magistrate. Petty jealousies were common among the officers and, when it happened that some bombastic fellow took to bullying another who considered himself rather the better, there must naturally have been ill-feeling.

The new Militia Ordinance was published on the 16th of April, 1856. The battalion consisted of 330 men, 200 of the line, 100 Rifles and 30 Cavalry. The names enrolled were put in one box and numbers in another, the drawing, was done by two boys at the Public Buildings. Substitutes could be provided if they also were qualified. Every year, one-third would be drawn in a similar manner and allowed to retire, their places being filled by others drawn from the remainder. They were bound to provide their own arms, accoutrements and uniform. All these and other provisions were to be enforced by fines and even imprisonment.

Parade of the Blind and Lame

The first parade was held at Eve Leary on the 20th of May. According to the Gazette, about 150 out of 207 drawn for the line were present; the majority claimed exemption on some ground or other. Some were blind, some lame and one in particular could not march without the assistance of a wheel-barrow. Some had not income enough, others not strength enough, none had courage enough to do their duty. It was questionable whether the adjutant, with all his soldier-like qualities, could ever lick such a motley crew into a presentable shape or give them the air, much less the heart, of soldiers. One gallant captain with 44 men had 37 who claimed exemption and, of the remaining 7, five were the most emaciated of the whole muster; another had only 2 effectives.

This would never do. Two boards were therefore appointed, one to examine claims to exemption, the other, medical, physical ability. As a result of their investigations, 120 out of the 207 were exempted and a new ballot took place with somewhat better results. But, even yet, there were difficulties in getting anything like subordination. In August, a court-martial was held when fines were imposed. One who fixed his bayonet and wanted to stab his captain was fined $25 and, in default of payment, was sent to the debtors’ ward in the jail. Another was fined the same amount and a month’s imprisonment.

If the authorities had aimed to make the force unpopular, they could not have gone about it in a better way. Amending Ordinances were passed in 1857, 1858, 1859, 1860 and 1861, but none of them did much to improve matters. True, the Militia was kept up in a fashion until about 1870, when it fell in abeyance. The laws remained but they were not enforced. In 1872, a new ordinance was passed but that also remained a dead letter, for the old Militia was dead. No doubt, it would have been kept up if the people had seen the real necessity for such irksome proceedings as drill and parade but, as everyone felt that they were quite useless, nothing could make them perform their duties with other than unwilling minds. Public duties carried out under fear of fines and imprisonment never can be done by Britons in anything but a halfhearted manner.

The Volunteers

Now we come to a better sort of thing, the establishment of a Volunteer force. On the 8th of December 1877, a notice appeared in the local papers signed by the then Mayor, Mr. R.P. Drysdale, stating that he had been requested to call a meeting to form a Georgetown Volunteer Corps. Accordingly, he convened a meeting at the Assembly Rooms, on the 13th of the same month.

The Gazette spoke well of the movement. For six or seven years, the young men had no opportunities of regular and systematic drilling, thanks to a body of selfish and narrow-minded patriots, who succeeded in rendering the Georgetown Militia so distasteful that the then Governor found it desirable to suspend all parades until the corps was put on the new and more popular footing.

Nothing could restore the Militia to popular favour. It was almost certain that its resuscitation would be the signal for a renewal of the quarrels and discords which totally deprived it of its usefulness. But, to some, the old Militia was a source of enjoyment and health; the change from the tedious drudgery of desk or counter to the exhilarating duties of parade was beneficial to both mind and body and its objectionable points would not belong to a Volunteer force. The meeting was held, it was resolved to establish such a force and ultimately it numbered about two hundred. But the enthusiasm so conspicuous at first soon gave place to coldness and it became very difficult to keep it up to an effective standard.

The Volunteer Militia

In 1891 when, for the first time in the history of the colony, the military force was withdrawn, a new ordinance was passed, under which the present Volunteer Militia was established. Arrangements for enrolling were again made and it is understood that if volunteers in sufficient number are not forthcoming the ballot will be put in force. Under a system of payments for attendance at drill and deductions for breach of regulations, this system has worked fairly well, and fortunately there have been no cases in the Magistrate’s Court for some years.

In reviewing the story of the Militia we cannot but remark that its place is now taken by the police. When its laws were strictly enforced there were absolutely no police; the officers took the duties which now devolve on police inspectors and commissaries. Never was any attempt made to use that force to defend the colony and, when calls to surrender were made by the enemy, only the small garrison was taken into account. It is very doubtful, however, if these colonies could be defended properly except by a naval force. There is nothing to prevent the landing in boats of a sufficient force to overcome all opposition. When the British arrived in 1803, they came prepared to land troops anywhere along the coast and the Dutch authorities knew well that opposition was useless. The French, in 1782, brought the British to terms by threatening to destroy the plantations. Long ago, the same thing was done in Essequebo; French corsairs compelled Kyk-over-al to surrender by pillaging and burning the estates in its neighbourhood.

Dr. Lushington, counsel in the case before the Privy Council of Hughes v. McTurk, 1829, said : The establishment of the Militia may be a very fit and very proper establishment for the safety of the colony but, surely my lords, under circumstances like these, nothing can be so important, so indispensable, for the welfare of all concerned, as that the Militia itself should be governed by the most lenient rules possible and that no attempt should be made, under colour of discipline, to inflict upon the persons, compulsorily forced to serve in it, hardships or injustice, to which they ought not to be exposed.