On November 17, 1978 Neville Annibourne flew to Jonestown in his capacity as an Information Officer with the then Government Information Service. The next day he became an eyewitness to part of a macabre tragedy that brought Guyana to worldwide attention.

By Neville Annibourne

Thirty years can seem like 30 days when events of the magnitude of the Jonestown Tragedy have etched themselves on your memory. Jonestown was as unique as it was macabre. That is why its memories cling to you in the same way that the stench of the tragedy persisted long after the bloated corpses had been removed from where their lives had been taken from them.

In November 1978 I was an Information Officer with the Govern-ment Information Servic-es under the Forbes Burnham administration. Those were different days. I remember, for example, that the media was – more or less – a state tool and that people came to know far less about some of the really important issues that took place in the society. Jonestown was one such issue.

With hindsight there was a dark side to Jonestown, a side that unfolded suddenly, quickly, exploding with a fearful intensity into a macabre tragedy that claimed 912 lives and, in a sense, put Guyana “on the map” so to speak.

Not that we were “off the map” prior to the Jonestown Tragedy. We were not. We were Caribbean; we were underdeveloped and we were experimenting with what the Burnham administration called co-operative socialism. That meant that we were pursuing a brand of self-reliance, that we made our own rules and that there were those who made the rules and those who followed them.

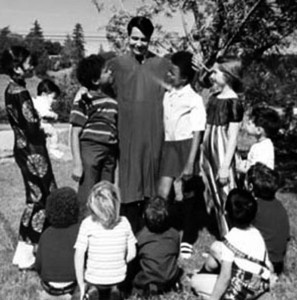

In a sense Jonestown fitted into the co-operative socialism matrix and into the broader context of a Cold War. Jim Jones was an eccentric cultist with a following in San Francisco and the prying eyes of the open American society made him uncomfortable. The political culture of Guyana embraced the rebellion of Jones and his cult against American imperialism while the preoccupation of the local political administration with repelling what was described in those days as Venezuela’s expansionist ambitions facilitated Jones’ search for a remote interior location in which to hide his madness.

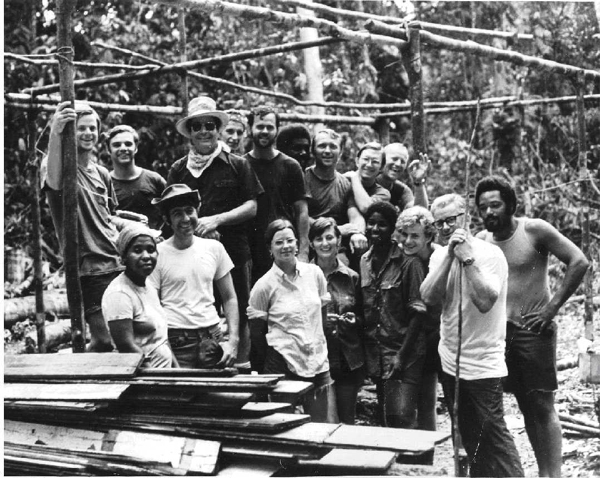

Jones had a predisposition for agriculture that fitted in with the fact that his followers provided all the unpaid labour that he needed. It fitted in too with Burnham’s brand of an agrarian revolution. He came with his following and in those days that was that. No questions; no queries; there was no room for that in our political culture.

There are those who claim that the Jonestown Commune was a state within a state; that Jones – in a macrocosmic kind of way – wielded as much power as Burnham in his smaller kingdom; that he possessed millions of dollars and a capacity for mind control. I know nothing of those things, I was only an Information Officer with the GIS and like so many others in my time I treated with information on a need to know basis.

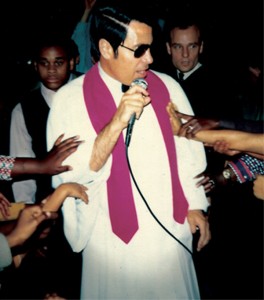

With hindsight there were things that were different about Jonestown. The few members of the commune – The People’s Temple – who showed up in Georgetown from time to time were excessively polite, warm and clearly fiercely loyal to Jim Jones. The commune may have been the physical manifestation of what their life was all about but Jim Jones seemed to be the very essence of their existence. The fact that he was described as the Reverend Jim Jones did not appear to be indicative of any overwhelming adherence to Christian beliefs. From what we used to hear worship was a mish mash of rites and rituals designed to underscore the deity that Jones symbolized. For all we know Jim Jones may well have sold himself to his followers as God Almighty.

I believe, however, that the essence of the Jonestown tragedy lay in the fact that we knew so little about what he represented and ignored the little that we knew. The man had come to Guyana with a past that was part criminal, part eccentric and with a following of people who appeared to have given their lives over to him in an unconditional kind of way.

Since Jonestown and with the evolution of media freedom and access to information we have come to know much more about cults and their obscenities. Back in those days we knew rather less and as far as we were told Jonestown was a thriving community of Americans who were essentially minding their own business and farming. That, in a sense, was the misfortune of flawed governance that subscribed to the view that Guyanese really needed to know no more about Jonestown than they were told.

That is why I have always resisted the notion that Jonestown was what is sometimes described as an American tragedy. You really cannot make that kind of argument when 912 people die suddenly and violently in your country having been invited to settle there by the government of the day. Their deaths may have been connected to what Jones regarded as the end of the line, but the evolving circumstances that took them to that macabre place were played out in our country. If we had troubled ourselves to monitor Jonestown closely we may well have been able to save those lives.

Once it became known that Senator Leo Ryan was coming to Guyana to investigate concerns raised by relatives of members of the commune we really should have been alerted to the possibility that Jonestown could implode. American senators are not in the habit of flying to banana republics (that is how we were perceived in those days) for flippant reasons and what we know now is that Jim Jones had every intention of creating mayhem once the senator set foot on his commune. I have asked myself too whether an American senator ought not to have been accorded some measure of local security particularly since it was well known that Ryan’s encounter with the People’s Temple was likely to be tense – to say the least.

I was assigned to “cover” Senator Ryan’s visit to Jonestown by Vic Forsythe. Vic was then the Chief Information Officer and a man who understood the complexity of the local media conundrum. With hindsight they probably could well have done without me since, in my capacity as a Government Information Officer I really was not expected to do the kind of story that contained all the ‘colour of what was to play out at Jonestown. My account of the senator’s visit and his eventual death would have been vetted and doctored to pieces, enough to ensure that the events were exactly what the media minders wanted it to be; and for all I know it may never have seen the light of day in the media. The truth is that if I had lost my life at that airstrip at Port Kaituma it would probably have been for nothing.

I met Senator Ryan at the Pegasus Hotel. In those days it was the only hotel in Georgetown befitting a United States senator. A few concerned relatives, a handful of journalists and two lawyers whom I got to understand were representing the People’s Temple were there as well. Less than a day later scores of other journalists from the United States, Britain, the Caribbean and elsewhere were to pour in to Georgetown, collapsing the fragile official propaganda machinery with their searching questions and their persistent poking around. Media, free media that is, work by rules that are driven solely by the magnitude of the event that they cover; and in the sheer scale of the tragedy that was Jonestown there could be no bigger story. The journalists came in hordes, by whatever means they could and the doctored official briefings provided by the government failed to serve their purpose, that is, to direct the attention of the media away from the real story. Those briefings stood no chance against the tenacity and the professionalism of the free media to which we were altogether unaccustomed. They simply took the country apart.

When I met Ryan at the Pegasus he was trying to make telephone contact with Jim Jones in order to get permission to enter the temple. Making contact with the interior by telephone in those days was like trying to perform a small miracle. In those days there was no GT&T. There was something called the Guyana Telecommunications Corpora-tion that did the best it could. Invariably, its best was simply not enough.

Ryan, of course, was American, a senator and had come much to too far to be thwarted by the inefficiency of our local telecommunication system. He got permission to go to Jonestown and we set off from Timehri for Port Kaituma. The journey was eventless save and except the foreboding that hung in the cabin like a Sword of Damocles. No one felt for a moment that the day would end as quietly as it had started though I have to admit that no one suspected that our mission would end in the loss of more than 900 lives nor, for that matter did Senator Ryan think that he would be such an intimate part of the tragedy.

Jones, we were told when we got to Kaituma was ill. His wife met the senator and his party and we were taken to the People’s Temple by a tractor and trailer, a significant climb-down, I thought, for an American senator. We met Jones later. He was full of apologies for his earlier failure to welcome the senator.

The congressman was blunt about the purpose of his visit. The people at Jonestown had relatives in his constituency who were concerned about the People’s Temple. He had come to investigate those reports.

Jones assumed an expression which suggested that he was hurt about the accusations. He denied them vehemently. When he asserted that his followers were free to leave the commune there was no conviction in his voice. The senator, I believe, knew that he was lying.

Not even the ‘concert’ staged for the visitors that night served to disperse the tension that hung over the commune. That all was far from well was evident though none of us would have suspected that Jones was hatching such a macabre finale.

At the end of the concert Jones ordered the concerned relatives and foreign journalists to leave the commune. That, for me, was a sign that he knew that the game was up. What I believe he feared most was that the visiting journalists would gather the evidence that would ‘sink’ him or perhaps that the concerned relatives would use the cover of darkness to simply spirit their relatives away. In my view it would have been impossible for Jones to even contemplate allowing his followers to abandon him. It would have meant conceding the madness of his People’s Temple, surrendering to the “American imperialism” which had been the bane of his existence and which was symbolized by Senator Ryan. Without his following Jones would have been reduced ‘from Christ to criminal’ and he would probably have been eventually dragged off to the United States to answer the charges he had left behind and to spend time in prison. That, for him, was not an option. In his sickened mental state the actualization of his white night in mass murder and suicide marked the final manifestation of his power over people.

I was a state media functionary and there was nothing to fear from me.

I remained behind with Ryan, his aide and Mr. Dwyer, the then US Deputy Ambassador to Guyana. With hindsight that made us prisoners of Jim Jones. There was really nothing to stop him from starting the ritual that very night and making us its first victims.

To this day I still wonder why a United States senator and a senior United States diplomat were allowed to travel to Jonestown under the circumstances that they did without even a semblance of local security.

I doubt that any of us slept well that night and the next day brought with it even stronger forebodings of disaster.

Jones was visibly agitated and his countenance infected the entire commune. I remember that he agreed to be interviewed by the visiting pressmen only after his attorneys persuaded him that it would be “good for the commune” if people in the United States could hear his side of the story. That morning, he seemed like a child, throwing tantrums, raising then lowering anxiety levels then suddenly raising them again. It seemed to me like pure theatre.

It was at the end of the interview and during the tour of the facility that things really begun to fall apart. As the tour proceeded members of the cult were simply attaching themselves to the tour party and declaring that they wished to leave with Ryan.

At the end of the tour the congressman confronted Jones with the demands of the defectors. Jones said they could go but by now the transparency of the lie was evident.

The Americans played along and Dwyer radioed Georgetown and ordered two aircraft.

The knife-wielding cult member who almost cut the senator’s throat as we were getting on to the truck to return to the Port Kaituma was a harbinger of doom. I knew then that our lives were in danger. At that moment Jonestown seemed like another country, a hell on earth that was somehow disconnected from our sorry little country. Home seemed a million miles away.

In a funny kind of way the shooting that started at the airstrip later broke the tension that had persisted during the earlier hours. Jones, we realised, had begun his macabre dance of death, his threatened Armageddon. It seemed to me that handfuls of pebbles were being thrown at the plane then I realised that no pellet could have blown the top of Patricia’s head off. Captain Spence’s efforts to get the aircraft off the ground were in vain. The tyres had been shot out.

The shooting stopped then started again then stopped altogether. I saw the tractor and trailer with the assassins drive off into the jungle. The congressman was dead and I suppose that by then the final chapter of the People’s Temple had begun.

The rest has been chronicled in books and television documentaries and the various investigations that followed. As for me I returned to Georgetown – thankful that my life had been spared – to a de-briefing by Forsythe and Shirley Field-Ridley, the Minister of Information. I remember being stunned over the news blackout in the capital. How could events of this kind of magnitude be kept from people?

For several days we continued to speculate over what was happening in Jonestown and when the news of the murder/suicide ritual finally came through we begun to speculate over the number of victims.

The Americans came and airlifted their dead out of the jungle and repatriated them with as much dignity as they could muster; and as far as we were told all this was “an American problem” and that we were no more than unfortunate witnesses to history. Thankfully, we no longer have to live with that folly.

3

Events like Jonestown inevitably leave a permanent scar. So it has been with Guyana. I remember the long after the murder/suicide ritual, journalists were still finding their way to Guyana to report on the country where the People’s Temple imploded; much of the reporting had nothing whatsoever to do with Jonestown. It was simply a question of curiosity and an eagerness by the rest of the world to learn more about the country that had hosted Jim Jones and had itself become a victim of his madness.

Funny enough, the events of Jonestown appeared to leave no permanent scars of the Guyanese people. I may be entirely wrong in my assumption vut apart from the inevitable political fallour, the blame game that is an integral part of our political culture, people appeared minimally affected. It seemed to me that most of urban population simply choose to live with the position taken by the political administration that Jonestown was really not our business.

Nine years after the tragedy Jonestown resurfaced in my own life, suddenly. I was served with a subpoena by the United States State Department to give evidence in the Larry Layton, apparently the head man in Jim Jones’ death squad.

Layton, a former member was charged with aiding in the murder of Ryan and US diplomat Richard Dwyer. As it turned out District Judge Robert Peckham setermined that my testimony was not needed.

On the final day of the trial I was invited to attend court and there was something about my being present and hearing the court sentence Leyton to life in prison that brought closure to my Jonestown experience.

After the sentence was handed down I was invited to Judge Peckham’s office. He too was curious about Guyana. I told him as much as I could but I did not expect that he would fully understand all the nuances of a country that was different from his own. The United States was the leader of the free world, the capitalist world and Guyana, relatively speaking, was a virtually unknown country, somewhere in ‘South America’ with a socialist dream that had already begun to fall apart. Our countries, however, mine and Judge Peckham’s did have at least one common experience – the experience of a madman, America’s madman whose madness had enveloped Guyana in what remains one of the weirdest experiences in recent history.