Colin Klass’s refusal to step down as President of the Guyana Football Federation (GFF) in the face of the rejection of his leadership by the players whom he purports to represent may have plunged local football into its most serious crisis ever.

It matters not one iota that the constricting rules of FIFA and the short-sighted refusal of his executive and general council and the various associations across the country to break ranks with him continue to keep him in office. By clinging defiantly to the presidency of the GFF, his overwhelming unpopularity with local football’s key stakeholders notwithstanding, Klass runs the risk of causing the GFF to come to be seen as no more than a despotic cabal ruling local football with an iron fist.

It is not just the game that could be brought into disrepute, it is the entire institution. More than that, Klass’ posture reflects a concern with the bureaucracy of football rather than with the game itself.

Interestingly, it is this preoccupation with the privileges rather than the responsibilities of leadership which perhaps more than anything else, has left sport in Guyana hobbled and underdeveloped and condemns our sportsmen and women to careers riddled with underachievement and frustration. In a sense, the crisis that is gripping football is a microcosm of a broader epidemic afflicting sport. The legitimacy of leadership, is derived not just from procedures laid down in rule books. Legiti-macy, in its essence, derives from the popular support and trust of a constituency. In the case of football, it is the trust and confidence of the players, the fans and those who otherwise give to the game from which leadership is derived; and when that trust and confidence is reduced to a near unanimous call for a change of leadership, it is time for the incumbent to go.

It may well be that Klass perceives his declaration that he intends to remain the boss of local football, despite his unpopularity, as a demonstration of toughness in the face of adversity. What he may well have done, however, is to place local football on a precarious perch from which it could very easily slip into chaos.

If the truth be told, Klass’s posture is not unique in local sport or, for that matter, in other fields of endeavour. His determination to stay put is, more or less, an emulation of what, for want of a better expression, has become a national habit. Local sport has other examples of bosses whom, their lengthy and invariably unsuccessful tenures having reached an ignominious end, resort to rules and procedures and sometimes to sheer force of will to delay their downfall.

The sad part of this practice is that those who are most reluctant to surrender the trappings that attend high office are often those who are least capable of recognizing the critical nexus between sport and nation-building. Protracted rule invariably engenders fanciful notions of a right to rule. Inevitably, those who rule come to see themselves as embodying the very institutions that they were elected or selected to lead.

Klass’s fall from grace has been incremental, evolving over a protracted period of an absence of any real growth in the local game and, more recently, in an exploded wellspring of pent up frustration among a talented but tired group of young Guyanese athletes whose performances on the field of play are, in fact, fierce personal battles to better their lives and the lives of their families. Their public remarks reflect a very real fear that their efforts, for themselves and for their country are really going nowhere. And in the final analysis it is, in large measure, the refusal on Klass’s part to understand their fears and their frustrations that has influenced his decision to stay on.

In a sense, the crisis confronting local football is a function of changing perceptions of what the game represents. Neither the players nor the nation as a whole are unmindful of what the game can do for them and for their country. The appearance of Jamaica and Trinidad at successive World Cup Finals have led, understandably, to exalted expectations.

We too want to play on football’s greatest stage; and even if we must wait our turn we want to be reassured by evidence that a base is gradually being built. That too is one of the reasons for the loss of confidence in the entire Football Federation. Elsewhere in the region, the success of the game has been built on a collaborative effort involving public and private sectors and the national federations.

Here, the GFF has postured as a law unto itself – which in fact is what it is – and in the process it has failed to secure the support of those without whom it can take local football no place. That, many people argue, has been Klass’s biggest failing.

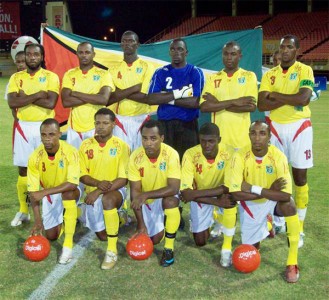

The Crown Plaza confrontation was an ugly and inevitable manifestation of the last straw, a playing out of the total and utter frustration of those who matter most, the players. That too, matters little. Real power, after all, does not repose in those who do the most for Guyana’s football – the Golden Jaguars – but with the rules that maintain the status quo and with what – in football as much as in politics – is almost always an inner circle that jumps ship in their its own time.

The question is, what happens now? The Golden Jaguars appear to have backed away from their earlier call to their fellow players to boycott Federation-sanctioned games after Klass had made it clear that even that would not move him. His only concern, it seems, is with his control of the bureaucracy of the sport, protected as he is by a thicket of rules and a handful of lieutenants who appear to care sorry little for the real game.

In the final analysis the whole sorry affair reduces the sport to a charade, a farce and when, finally, Klass makes his final exit from the stage it will take strong and committed leadership to retrieve the pieces of local football.