Omeros returns to the spotlight

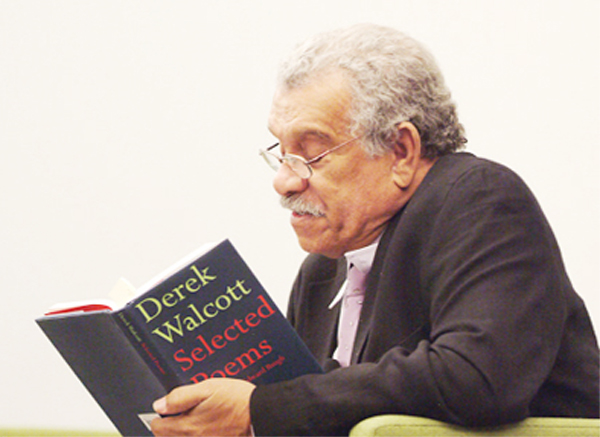

Derek Walcott’s exceptional 300-page poem, Omeros, which received immediate universal acclaim as soon as it was released some 18 years ago, returned to the world spotlight yet again recently. The epic work, hailed as the crowning achievement which won its author the Nobel Prize in 1992, was revisited and offered once again to an international audience which was treated not only to its fine poetry, but to a reminder of its application to wide-ranging issues beyond its pages.

This focus sharpened as two Nobel Laureates were distinguished guests of

the BBC. Their featured writer for the month of November 2008 was Derek Walcott, while it was the turn of American novelist Toni Morrison in December. The artists were interviewed by the BBC World Service presenter, read selected passages from their work and fielded questions from members of the audience. These were pre-arranged questions from two sets of invited audience: a select group of critics and students who were in the studio and a few others from different parts of the world who were invited to studios in their own countries from where they could listen to the broadcast and pose their questions.

It was part of a busy tour for Walcott, whose engagements after Carifesta X in Guyana included an appearance at Cave Hill in Barbados just before the BBC in November and a projected return to the Caribbean in the summer of 2009 to be honoured in Trinidad at St Augustine. After several years of university work in Boston, the world’s leading poet/playwright is now a “fortunate traveller” yet again, well in demand for tours while still returning to Boston on a part-time basis. As he told the BBC, he also still maintains a continuous presence in St Lucia although he lives in the USA. The celebrated writer has also lived and worked through major periods in his life in Jamaica, where he first went as a university student, and Trinidad where he founded a historic theatre company and developed his career more than anywhere else, but wherever his current residence, Walcott is now firmly naturalised as a citizen of the world. Few things will confirm this adoption of the writer than the ease with which he was named in 1993 as a serious contender for appointment as Poet Laureate of Britain.

Walcott’s own response to the speculation at the time was half amusement. One would not have thought it was an office that would sit very comfortably upon him, given the cynicism and mild disapproval with which he regards governments and officialdom. As he told the BBC last November, he never liked to write commissioned poems, and those who write poetry would know it is not easy to get inspired by and convert a manufactured theme and subject into creative art. That same disinclination to commissioned and duty-bound royal verse was expressed by Philip Larkin, another favoured choice for British Poet Laureate. But in that BBC interview, Walcott confessed that, despite his horror at the very idea, he did achieve satisfied success with what started out as a commissioned poem.

One of the questions from the studio audience had to do with Walcott’s adaptation of The Illiad by Homer, one of the greatest epic poems by the greatest epic poet in western literature. As expected, Walcott’s response was that Omeros was not an adaptation of The Illiad, but that it was much more and much more complex than that. He pointed out that it is primarily a drama of St Lucia and that several characters and elements of plot are not to be found in The Illiad at all. The truth of that is obvious, despite the many clear cases of derivation and intertextual engagement. One of the sections read to the BBC audience by the poet was a central focus of the work: the rivalry between Achille and Hector, two St Lucian fishermen.

They get into a fight on a beach where fishing boats are moored. This fight breaks out over a trivial item, an object used to bail water from a boat, nothing that one would think was worth a conflict so deep, bitter and full of passion. The obvious sub-text is that that is not the real reason for the hostility at all; behind it there is a woman. The real rivalry between the men is over the attractive Helen, who works as a maid in one of the large hotels on a neighbouring beach and as a domestic for a prominent family. This plot is taken from the story of the Trojan War told by Homer, although in that story well known in Greek mythology, Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, was the wife of a king of Greece whose abduction by Paris, Prince of Troy sparked off the bitter destructive war that lasted 10 years and divided not only the Greek empire, but the very gods on Mount Olympus. One of the events that brought the war to its end with the defeat of Troy was the famous battle beween the great heroes, the eventual victor Achilles of Greece and the defeated Hector of Troy. The Greeks’ final decisive assault was the trick played on the Trojans with the gift of the wooden horse.

Other borrowings from Greek myths include Philoctete with the incurable wound. Walcott’s St Lucian Philoctete’s eternal wound was eventually cured by herbs from an obeahwoman. It is a wound from slavery, one of Walcott’s many symbols and themes including Helen herself, symbol of the island, exploited, the object of centuries of wars between great rivals the French and the English, changing hands between them 14 times in history and described elsewhere by Walcott as ocelle insulare and the Helen of the Caribbean. There are themes of colonialism, independence, class, the sea, tourism and other issues. Walcott explained some of them including what he says happens to be parallels and similarities between Greece and the Caribbean, such as dependence on the sea and its influence, their hundreds of islands and their history of wars.

Greece and the classics have been favourite subjects for Walcott since the dawn of his career in the 1950s. Omeros is a mere revisit of The Illiad for him, as his explorations of them have included the play Ione, the long poem Another Life and the play The Odyssey in which he dramatises and Caribbeanises Homer’s other great epic. For him they have been parts of his and the Caribbean’s English education and a valued heritage which, unlike many other writers, he does not regard as colonial curses.

Although several critics have given him the title, Walcott has stopped short of calling himself the “Homer of the Caribbean,” even though he made a vow in verse decades ago to do for the region what Homer did for Greece. Omeros is actually the Greek name for ‘Homer’ and Walcott has made much of it, as he did again to his BBC audience who also asked whether he was paying tribute to these Europeans Homer and Dante, and why he was doing it. Walcott has no problems with them being Europeans and of paying them homage. Even colonialists, pirates and slavers he acknowledges in other poems as “ancestral murderers and poets.” In an essay called ‘The Muse of History’ published ironically in a collection of essays edited by Ordre Coombs called Is Massa Day Dead? Walcott praises some of the positive inheritances from “massa day” such as the English language.

As an artist, he finds it an integral part of his trade to acknowledge, pay tribute, benefit from or artistically engage work that other artists have done. That is his approach to Homer and to the Italian Dante. In Omeros he avoids the almost natural heroic couplets to use, instead, the terza rima employed by Dante. Walcott found it difficult to do, the rhyme scheme was a challenge and he explained how, often as he wrote he literally did not know where his next rhyme was coming from. The verse form utilises three-line stanzas with rhyme that carries over into the next stanza making composition very demanding. He is not bothered about European forms in a West Indian poem and finds significant relationships in the poetic craft of the different traditions. In previous discussions in the 1980s, for instance, he said that while writing The Joker of Seville, his dramatic version of the Spanish Don Juan, he found it easy to write iambics because of the closeness to the rhythms of West Indian speech. The

use it, and so does Walcott in his very Trinidadian tribute to the Trinidadian calypsonian in the satiric poem The Spoiler’s Return.

Yet Walcott is not a colonial, neo-colonial, conservative, conformist or ‘Uncle Tom.’ There are radical, critical views that he will vent loudly at the slightest opportunity. The BBC appearance provided such an opportunity, as did Carifesta X where he took on the President of Guyana. The radical view was about tourism and a notion of development that he calls “prostitution.” His target was a favourite one of his – Caribbean governments. Someone raised a point relevant to the treatment of the big hotels and tourism in St Lucia which he satirises in Omeros. He renewed his attack on Caribbean governments for their selling out of the national patrimony for money from tourism – prostitution which they call development. He lambasted the big, all-inclusive hotels and their displacement of national cultural heritage, much as he did during Carifesta.

That, too, is an issue treated in Omeros, a work unapologetically based on classical literature but made meaningfully West Indian. It is work with which Derek Walcott has been interested throughout his long career, sometimes struggling with a satisfactory form within which to present it, and with it as a subject in the face of prevailing post-colonial positions. He most recently came into conflict with those positions in 2002-03 during the performance of his play Haytian Earth in Trinidad. It is work with which he has found considerable success as in The Odyssey, a play commissioned and performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-Upon-Avon in 1992 and sold out at The Barbican in London in 1993. Although faithful to Homer in his plot and characters, Walcott produces a very Caribbean play. A notable departure from Homer, but a useful introduction to suit the drama, is Billy Blue, who, however, plays the role of the blind seer epic poet. While still being faithful to Homer, because the original allows it, he is able to turn Odysseus into a West Indian trickster Anansi figure.

In works like these the celebrated Nobel Prize winner finds satisfaction and absolution for a position he has maintained for 46 years. Commenting on the bloody uprisings in East Africa all those years ago, he asked “how can I choose between this Africa and the English tongue I love?”; “how can I face such slaughter and be cool?”; “how can I turn from Africa and live?” But at the BBC in November 2008, nobody asked him about Darfur, the Congo, Rwanda or Zimbabwe. Perhaps they thought none of it was relevant.