The rebellion that erupted forty years ago on Thursday, January 2, in the Rupununi District has been the single most serious threat to the national security and territorial integrity of the state. Occurring only thirty-two months after Guyana’s independence from Great Britain, it also constituted the country’s earliest and severest test of statehood and social solidarity.

It has always been an error to assume that colonial subjects yearn to become citizens of an independent state. In the case of British Guiana, the so-called independence struggle was more problematic than elsewhere in the anglophone Caribbean. On much of the coastland, the rivalry for political office aggravated ideological, social and racial differences and left deep wounds which never healed completely. In the hinterland, the Rupununi District’s remote location, quaint socialisation and poor communication contributed to its low level of integration with the rest of the country. Dangerous delusions and feelings of exclusion festered there.

The regional context

Prior to independence, the Rupununi District’s spatial, settlement and land use patterns and under-populated and under-resourced conditions set it aside as a ‘frontier society’ in significant ways.

Geographically, the Rupununi is different to anywhere else in Guyana. Located in the southernmost and remotest part of the country, it was the country’s largest district of nearly 58,000 km² or over a quarter of the national territory. Its most prominent feature is the savannah but its economy is precarious. Cattle-ranching had been introduced in the 1860s and, a century later, by the 1960s, there were about fourteen major ranches with 18,000 head of cattle scattered over the north and south savannahs. The huge Rupununi Development Com-pany based at Dadanawa had about 25,000 head.

In the colonial era, the land was ‘Crown’ land. The Rupununi Development Com-pany operated an enormous ranch of 6,734 km² (about 2,600 square miles) under a 21-year lease. Individual ranchers were leased blocks of about 130 km² (50 square miles). After five years, tenants were eligible to obtain 21-year leases with renewable rights, provided that stipulated stocking and building requirements were met. But conditions were always marginal. The soils are loose, low in nutrients and unsuitable for intensive farming. Grazing no more than six head per square kilometre (or about 15 cattle per square mile), stock management could be cursory yet costly. Transportation was also expensive; market cattle slaughtered at the Lethem abattoir had to be carried by air to Georgetown.

The district, nevertheless, had started to evince encouraging signs of progress by 1968. It possessed an abattoir; aerodrome; hospital with government medical officer and nurses and a dispensary supplemented by missionary medical services; police stations; primary schools; sections of the Public Works and Lands and Mines Departments; trade store; electrical generating plant and a reliable air and mail service from the coastland. A useful livestock station functioned at St Ignatius. The Easter rodeo, a hotel and a few nightspots provided entertainment.

The Rupununi District was home to three indigenous ethnic groups − Makushi in the north savannahs; Wapishana in the south savannahs; and Wai-Wai in the forested deep south beyond the savannahs. Public health measures to control tuberculosis and eradicate malaria triggered a population surge from 3,500 in 1945 to 12,000 in 1968 − relatively sparse in relation to the area.

Non-Amerindian settlement started about 1860 when a trader of Dutch ancestry named de Rooij established a homestead near the Rupununi River, not far from Dadanawa, and bought some cattle from Brazil. Next came Harvey Prideaux Colin (HPC) Melville, of Scottish ancestry but Jamaican birth, who by the 1890s bought the small herd of 300 after de Rooij’s death. Melville took two Wapishana wives − later known as Mamai Mary and Mamai Janet − and with them fathered ten children. Thus started a large clan of mixed Amerindian and European ancestry located first in the south.

The next prominent personality was Basil Lawrence ‘Ben’ Hart, an American who arrived in the Rupununi in 1913. Ben Hart met and married Harvey Melville’s eldest daughter, Amy, fathering six sons and a daughter. This had the effect of enlarging the class. Harvey Melville, Ben Hart’s father-in-law, established him at the Good Luck ranch at Pirara in the north savannahs. Four of Melville’s sons married Brazilian women of mixed blood and the fifth married a Wapishana woman, each offspring receiving land and cattle as a wedding gift. In time, a large cattle-owning caste of related families with common occupational, political, religious and social interests and lifestyle, and accustomed to holding sway over a vast domain, rose to prominence in the Rupununi.

The Christian church was well entrenched. Broadly, the Roman Catholics were strong in St Ignatius and the south and the Anglicans in the north, but several other missionaries, such as the Unevangelised Field Mission, were influential. Party politics came when the Rupununi District was designated as a separate electoral constituency and with the establishment of the United Force party in 1960. In the elections of August 1961, Edward (Teddy) Melville, MBE, was elected to the Legislative Assembly as member for Rupununi. Political mobilisation led to ethnic polarisation. The evidence suggests that resentment against coastlanders, in particular Africans and East Indians, had been fomented over a long period. Fantastic stories were widespread. Especially after independence, wild rumours circulated that the ranchers’ land would be taken away and given to African-Caribbean settlers from Barbados and Jamaica and the whole way of life in the Rupununi would be turned upside down.

The savannah oligarchy was able to live comfortably by 1968. Many of their children were educated on the coastland and ranchers and Amerindians together constituted an influential political constituency. Even before the rebellion, certain cultural characteristics had become evident. Describing the oligarchy, Michael Swan, in his The Marches of El Dorado, wrote:

“They now have money for the first time, they have jeeps, good clothes and can fly to Georgetown when they wish… Civilisation has brought them to a pleasant point of prosperity; they do not wish the savannahs to be settled by outsiders – perhaps the Negro from the coast; they do not want progress and development – perhaps a township where the Indians will learn all that is worst in modern civilisation.”

The significance of such a reactionary mindset and in such a social context was amplified sharply in the months after national independence in 1966.

The criminal conspiracy

What were the real causes of the conspiracy? Several factors – economic, ethnic, political, legal and strategic – might have motivated the ranchers’ fateful decision. During the rebellion, Valerie Hart, the self-appointed “President of the Essequibo Free State,” suggested that there was a racial factor. She told United Press International in Caracas, Venezuela, that the rebels were seeking “racial independence” from the “despotic policies” of the central government of Premier Forbes Burnham. James ‘Jimmy’ Hart, also in Caracas, explained that the decision to rebel was taken after the government refused the ranchers’ request for a 25-year lease of the land they were occupying and their fear that farmers from Jamaica and Barbados would be brought in thereby “forcing white settlers and Amerindians out.”

On the legal side, the land question had become an important national issue after independence. Honouring its commitments to the indigenous community, the administration had convened the Amerindian Lands Commis-sion under the chairmanship of Patrick Forte in August 1967 in accordance with the Amerindian Lands Commis-sion Ordinance 1966. Charged with determining the areas of residence and recommending rights to tenure and other issues, the commission’s recommendations were confidently expected to collide with the conventional lax land use patterns in the Rupununi. It soon became clear to all that Amerindian land rights could be determined and defended only to the detriment of the companies, churches and ranchers who had already established themselves in what until then they regarded as ‘empty’ Crown lands with little real concern for the economic interests of the indigenous people.

On the economic side, ranchers had been slow to adopt efficient, intensive animal husbandry practices which could have supported larger herds on smaller acreages. The short-term nature of the land leases, the prospect of an unfavourable ruling by the commission and the fear of competition for limited labour and land resources combined to heighten the ranchers’ insecurity. The ranchers saw themselves as an exclusive class who had transformed the district from a wilderness. Just when prosperity seemed within their grasp, they felt threatened by the possibility of having their privileges diminished.

On the political side, from the time that party politics came to the district, the oligarchy and the indigenous peasantry were regarded as supporters of the United Force party. One of their own, Edward Melville, had been elected to the Legislative Assembly in August 1961 and, in the elections of December 1968, Valerie Hart was that party’s unsuccessful candidate. After the elections of December 1964, the United Force entered a coalition administration with the People’s National Congress but, when it was excluded from the administration after the PNC claimed an outright victory in December 1968, the ranchers feared the worst.

On the strategic side, relations with Venezuela over the territorial controversy had deteriorated since independence. The Rupununi District was located wholly within Venezuela’s zona en reclamación and the ranchers must have felt that their hacienda lifestyle and social pretensions would have been tolerated under Venezuelan governance. In a clearly treasonable statement during the course of the rebellion, Valerie Hart urged the Venezuelan government to assert its “rightful claim” not only to the Rupununi but to the entire Essequibo region.

There was no evidence to substantiate the assumption that support for rebellion among the indigenous population was widespread. There was no apparent intention or effort to win their hearts and minds or to convince them that the rebel cause was worth fighting for. Some of the indigenous ‘foot soldiers’ recruited into the rebels’ ranks seemed to believe that they would be taken to Georgetown and had left their homes nine days before the hostilities.

Others would later claim to have been misled or intimidated into going to Venezuela for military training. The ranchers, and not the rank and file, had a clear political objective and military mindset and were prepared to seek the support of a foreign state to promote the secession of part of Guyana’s territory.

The rebel offensive

For an undertaking as serious as secession, the ranchers seemed strangely unready. There was little indication that they had tried to win over the indigenous population. Propaganda, such as it was, came only after the outbreak of the rebellion and was aimed at Venezuelan official and public opinion rather than winning support and sympathy in Guyana. Hence, the rebellion unfolded, exploded and imploded all in a matter of ten days.

On December 23, 1968, several ranchers met at Harry Hart’s ranch at Moreru where a plan for capturing the main government outposts and declaring the secession of Rupununi from Guyana unfolded.

The next day, some of them and their vaqueiros were flown to Venezuela and lodged in a military camp for seven days training in the use of weapons. The group was flown back to Pirara on January 2, 1969 and the same morning set out for their objectives. Valerie Hart was taken by the same aircraft back to Venezuela where she would present herself as “President of the Essequibo Free State” in revolt against the Government of Guyana, and claim that the inhabitants of the region had been “attacked without provocation.”

On arriving at Lethem, the rebels opened fire on the police station with the man-portable M-9 Anti-Tank Rocket Launcher (the so-called bazooka) and automatic weapons. Policemen rushing out of the building were shot dead. The rebels then entered the station and shot and killed one civilian employee, Victor Hernandez. The police inspector who was at the district commissioner’s office at the time of the attack was shot and killed there. The government dispenser who rushed to the police station when the firing began was shot at and wounded. The station’s radio communication with polïce headquarters in Georgetown ceased immediately after the attack began and before any messages about it could be sent. In all, six persons were killed at Lethem The rebels then rounded up the residents including the district commissioner and held them prisoner in the abattoir, blocked the airstrip and set up machine gun posts at tactical positions around the township.

Elsewhere in the district, other sections of the rebel force were despatched to block the airstrips at Good Hope, Karasabai, Karanambo and Annai; seize the small police stations at Annai and Good Hope; and shut down radio communications. This left open only the airstrip at Manari about 9 km ( 6 miles) from Lethem. Apart from the mayhem in Lethem, the rebel offensive had the effect of forcing hundreds of Amerindians to flee. About 300 crossed the Takutu River at St Ignatius to seek refuge in Bom Fin, Brazil. Others fled to the hills or hid in the bush. About 95 fugitives, probably members of the Melville-Hart clan, initially arrived at Santa Elena where they were granted asylum and promised land and employment by the Venezuelan government.

The rebellion seemed destined to fail. The small company of combatants received only about a week’s worth of military training on unfamiliar weapons in a foreign country. They squandered their superior knowledge of the terrain and failed to adopt field tactics to dominate the countryside beyond the seizure of a few centres and stations or to resort to irregular warfare to harass the Guyana Defence Force when it eventually arrived. Transportation by British Mini-Moke light utility vehicles was limited to poor roadways and little use was made of the light aircraft at their disposal. Communications and coordination were weak, the offensive collapsed in disarray and the rebels fled.

The military campaign

The military operation to suppress the rebellion was commanded personally by the Chief of Staff of the Guyana Defence Force Colonel Ronald Pope, a member of British Army Staffing, Administration and Training Team in Guyana at that time. The task force was drawn from the 2nd Battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Cecil Martindale and comprised three companies – No. 2 Company under Captain Vernon Williams; No. 4 Company under Captain Desmond Roberts; and No. 6 Company under Lieutenant Joseph Singh.

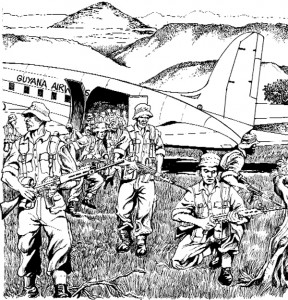

The earliest warning of disorder seems to have come from Guyana Airways pilot Captain Roland da Silva. On leaving Lethem in a Guyana Airways DC-3 Dakota aeroplane with a load of beef destined for Georgetown, he heard a radio transmission about disturbances over a missionary radio which was passed on to the government, Guyana Airways, Civil Aviation Department, Guyana Defence Force and Guyana Police Force.

At that time, the security forces possessed no transport aeroplanes and only Guyana Airways could mount a major airlift of a large number of soldiers over such a great distance. Three senior pilots – Michael Chan-A-Sue, Roland da Silva and Philip Jardim – and their co-pilots were ‘invited’ to volunteer to transport troops and supplies in a nearly 90-minute flight to the Rupununi. After the rebellion was quelled, Prime Minister Forbes Burnham commended them for their courage, commitment and skill.

Military mobilisation began at mid-afternoon on January 2 at the GDF’s 2nd Battalion Head-quarters at Atkinson Field (now Timehri) in response to Captain da Silva’s report. By nightfall, the advance guard of the military task force had been transported to Manari. During the night at Atkinson Field, more troops assembled and the next morning, January 3, task force headquarters and the main body landed. Orders were issued for the operation to be conducted in three phases: first, the capture of Lethem; second, the capture of rebel positions in the north and south savannahs; and, third, the restoration of central government authority throughout the district.

In the first phase, the attack to capture Lethem was led by two rifle companies. No. 4 Company was given responsibility for the western sector with the task of securing the administrative buildings and other structures along the Takutu River which formed the Guyana-Brazil border at that point. No. 2 Company was given responsibility for the eastern sector with the task of retaking the airstrip, abattoir and nearby structures. No 6 Company, which comprised the advance guard that had been flown into the area the previous evening, was initially given the responsibility to maintain the security of the airhead at Manari.

The month of January in the Rupununi is sunny and dry; visibility is good and the ground is firm. Under these conditions, the task force began its advance on Lethem on Friday, January 3, across open terrain. The task force met no opposition from the rebel force even though the latter possessed several tactical advantages − better knowledge of the ground; prepared positions; superior weapons; good fields of fire and vision; and vehicle mobility. The rebels, however, chose to get into their vehicles and drive off to Brazil.

Both companies secured their objectives. No. 4 Company, which came upon the sun-baked cadavers of the policemen, was given responsibility for Lethem area after it was retaken. No. 2 Company, which took the airstrip and abattoir, was able to free dozens of government officials and foreigners who had been held hostage. By 18:00 hours, the first phase of the task force’s mission was accomplished.

The second phase started from Saturday, January 4, as No. 2 Company was sent to secure the north savannahs and No. 6 Company was called up from Manari and sent similarly to secure the south savannahs. In general, the population had fled across the Takutu River to Brazil or into the bush and settlements were empty. Several of the abandoned ranch houses owned by the rebels were razed.

In the final phase, after across-the-border negotiation with Brazilian officials, refugees were encouraged to return home. By this time, border security had become the military responsibility of the Brazilian army’s Grupamento de Elementos de Fronteira which established control points to prevent unauthorised entry into that country. The Brazilian military authorities, however, refused to hand over rebel fugitives on their territory. Those still in Guyana who were suspected of involvement in the rebellion were arrested by the police for interrogation. Military patrols continued and peace and order were restored.

The political sequel

Despite the Rupununi’s relative remoteness from the coastland, the rebellion made waves at several levels in the country. The United Force party had many reasons to be embarrassed by the tragic fiasco. The rebel Valerie Hart had been one of that party’s candidates to contest the December 1968 general elections only a few weeks earlier but had failed to win a seat in the National Assembly. Her claims in Venezuela that the inhabitants of the district had been attacked “without provocation” and that the government was treating them in the most barbaric fashion were quite untrue. Her appeal to the Venezuelan government to intervene militarily to help the rebels and take over the district and to assert its “rightful claim” not only to the Rupununi but to the entire Essequibo was taken as treasonous.

Five days after the rebellion, the party was obliged to expel her “for acting in a manner inimical to the territorial integrity of Guyana and the aims and objectives of the United Force.”

In addition, evidence suggested that the party leader Peter d’Aguiar and his wife Kathleen had paid a visit to the Rupununi on December 28, soon after the general elections. They held an hour-long meeting with Harry and Valerie Hart and others but were in London when the rebellion broke out. The next month, denying knowledge of the conspiracy, Peter d’Aguiar announced his resignation from the National Assembly and his intention to quit politics.

The People’s Progressive Party opposition, mistakenly assuming that the rebellion was an indigenous insurrection, took the opportunity just one day after the rebellion to blame the People’s National Congress administration for what it called “the grave dissatisfaction among the Amerindian inhabitants” and for the “widespread and growing discontent.”

The People’s National Congress, together with its arms – the Young Socialist Movement and Women’s Auxiliary – held a huge rally on January 12 at Independence Park in Georgetown. Wearing black armbands, speakers condemned Venezuelan involvement in the rebellion and called for the expulsion of foreign missionaries; the trial of “traitors” in a military court; mass military training and the acquisition of weapons from China, Cuba and Russia “as a matter of survival to defend our fatherland from warlike neighbours.”

The central government reacted in several ways. At the security level, strict controls were imposed immediately on the entry of visitors to the district. Some foreign-born Roman Catholic priests were refused permission to return and officials of the United Force were banned from entering. At the administrative level, the Department of the Interior was transferred from the Ministry of Local Government to the Office of the Prime Minister. The month after the rebellion, 170 Amerindian toshaos were invited to a four-day conference in Georgetown. Apart from agreeing to a raft of community projects, the significant outcome of the conference was the unanimous passage of a resolution. In a staged show of support, the toshaos pledged their loyalty to the government, rejected Venezuela’s territorial claims; deplored the actions of “misguided persons who conspire with foreigners to the detriment of the state”; and condemned those who sought to overthrow the government by force, among other things.

A useless war

The police arrested a few hundred mainly Amerindians in the district on suspicion of having been involved in the rebellion, but only 22 were brought to Georgetown to answer charges for murder in the magistrates’ court on January 10. Warrants were issued for the arrest of several members of the Melville-Hart clan – the masterminds – but, by this time, they had all been granted asylum in Brazil and Venezuela. The following year, charges against the suspects who were remanded for trial in the high court were dismissed.

The rebellion had its roots in the peculiar geographical, historical and racial pattern of development of a remote region. Citizens in other parts of the country who were influenced by the plantation economy, populist politics, ideological diversity, intellectual ferment, racial rivalries, educational change and mass communication, had come to a sort of tense modus vivendi.

The Rupununi oligarchy, however, did not. The ranchers languished in paranoid isolation − hidebound and enmeshed in a web of obsolete, semi-feudal social relations.

In the final analysis, the rebellion was all about the meaning of national independence to different groups. The rebels did not have a single progressive objective and resorted to violence in a desperate attempt to preserve an irrelevant social order in changing times. Paradoxically, however, by destroying itself, the oligarchy removed the major impediment to the social integration of the indigenous Rupununi population in the emergent nation.