Change is coming in Cuba

In the last week Cuba has hosted receptions around the world to mark the fiftieth anniversary of its socialist revolution. In London the participants ranged from the chairmen of some of the UK’s biggest companies, through politicians from across the political spectrum to academics, artists, the professions, diplomats, officials, trades unionists and, of course, the sympathetic left.

Few other Caribbean events could have attracted such a diverse group of participants or demonstrated such high levels of support.

At the event, Cuba’s Ambassador made a quietly moving speech about how his country had resolutely, with dignity and through a deep social commitment been able to progress. In carefully chosen words he made clear that this had happened despite the desire of others outside to see Cuba’s economy collapse and its government overthrown.

His remarks like those of Cuba’s leadership should give pause for thought in capitals where the stubborn view remains that Washington in some way should be able to determine future Cuban history. Indeed one of the great curiosities after half a century of failed policies is how few in positions of power in Europe or North America ask why their approach towards Cuba has failed or why it should be that Cuba’s revolution – despite its many shortcomings – has not succumbed to external pressure and continues to move forward.

In Washington and in much of Europe the mind set remains that what Cubans require is a version of their systems of government. Thus in her Senate hearing to confirm her appointment as US Secretary of State, Hilary Clinton implied that what Cubans most desired was democracy, freedom and a free-market economy of the kind practised in the US. Despite this her remarks contained modulated language indicating a new US approach to Cuba policy: “We hope that the regime in Cuba, both Fidel and Raul Castro will see this new administration as an opportunity to change some of their typical approaches, let those political prisoners out, be willing to open up the economy and lift some of the oppressive strictures on the people of Cuba and I think they would see there would be an opportunity that could be perhaps exploited, but that’s in the future whether or not they decide to make those changes.”

Sadly, in saying this she again demonstrated the continuing failure of Washington to understand that what drives policy and actions in Havana is first and foremost nationalism and a uniquely Cuban culture and sense of society. That is to say Cuba has an innate sense of its own independence starting from the movements of the late nineteenth century and the wars of independence against the Spanish and the US, and is never going to negotiate this away.

So what might the world reasonably expect of Cuba in the coming years?

Firstly, it will continue to develop within the parameters of its own system, economic reforms aimed at providing for the social development of its entire people. In practical terms this means that the economic reform process that is underway will continue. Its focus will be on efficiency, accountability and probity, while offering material incentives through a more market-oriented Cuban approach that accepts salary differentials and the role of the market in a socialist economy.

Secondly, this process will ultimately not depend on either Raul Castro but rather on a new younger generation of leaders that have similar ideals, a unified approach and a sense of history, social commitment and continuity. The reorganisation of government later this year and the sixth Cuban Party Congress are likely to affirm this gradual progression towards the future.

Thirdly, the party congress is likely to agree far-reaching reforms in thinking, or what President Castro recently described as “structural and conceptual transformations.”

Fourthly, Cuba will undertake these changes on the basis of a new economy and new forms of economic organisation. This will ensure its economic survival, and underwrite its ability to integrate its economy with the wider world. Thus the stress will be on high-value knowledge-based industries such as biotechnology and informatics as well as the service sector more generally.

Fifthly, it will continue to develop its global non-aligned relationships and a policy of gradual integration into the Americas as alternative hemispheric political and economic poles to the US emerge.

And sixthly, it will seek to have a unified party endorse and lead these changes.

Anyone looking for clues as to how dramatically Cuba is changing should read President Castro’s late December speech to the Cuban National Assembly and later remarks on the anniversary of the revolution. In these speeches he variously suggested that the planned reorganisation of government would take place in late 2009; that this will happen by the time of the party congress later this year; that a new layer of government will be introduced in the shape of a powerful new body of General Comptroller beneath the Council of State able to audit ministries and enterprises and enforce standards, financial regulations and taxation; that changes will take place in the lifestyles of the elite through the cutting of gratuities and overseas travel; that all Cubans will work and that payment will only be for effort; that an income tax system for all is now near; that workers will be able to build their own houses; that certain activities such as taxi-driving and private farming will be freed from state control; and that the proposed changes to the labour code will be taken forwards.

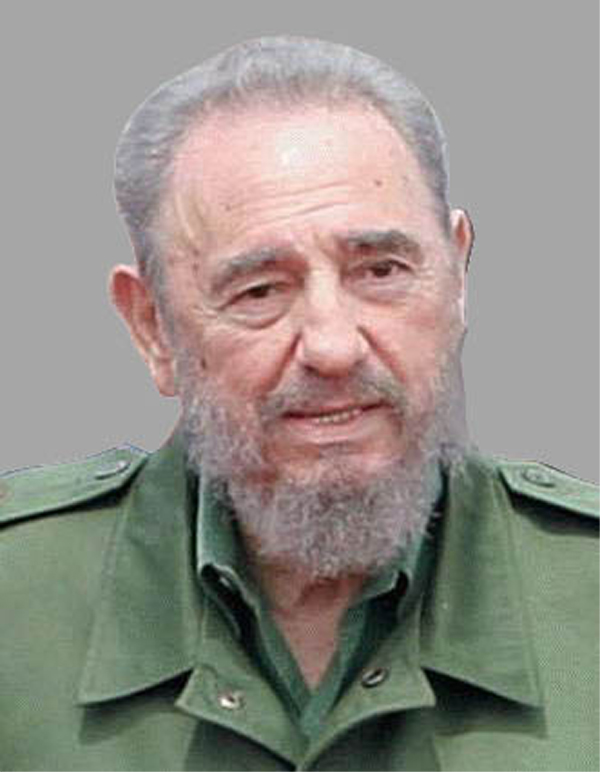

All this is happening as Fidel Castro is becoming more frail. His commentaries have ceased; he did not appear even in a picture on the 50th anniversary of the revolution and he did not see the Ecuadorian President when he visited. Despite this, when the moment comes his memory will continue to be a potent force in Cuba in the manner that a well-respected grandfather influences subsequent generations.

In common with almost every nation many of Cuba’s young do not have the same commitment and drive but want more materially. Their parents’ generation too have little in common with the fighters who took power from Batista and enabled Cuba to survive the Cold War. In the fifty years of its revolution Cuba has made mistakes, but arguably nothing on the scale that free market capitalism has demonstrated in recent months. Cuba is now moving on.

Previous columns can be found at www.caribbean-council.org