Rupert Hopkinson is loathe to discuss the business of books. The state of the book business he says is “an indication of a commercial culture that ignores a commodity that is as critical to quality of life as any. “From a purely commercial standpoint I believe that bookselling can be as profitable as any other private sector pursuit. The commercial sector has to help create that demand.”

Hopkinson says that booksellers the world over are likely to be people who love reading themselves. The pursuit, he says, is a marriage between a commercial venture and a personal passion for the product itself.”

And according to Hopkinson the local bookselling industry “is in a condition of flux.” Far too small to adequately support the intellectual needs of a highly literate society, the industry is “further infected with the taint of wanton copyright transgression which, to this country’s shame, unerringly targets our school system.”

Inevitably, he frowns on what he says is the indifference of the authorities to “a practice that amounts to the sabotage of both the book business as well as the efforts of writers to use their intellectual property to make a living.” Copyright transgression, he says, is really no different “to denying any other producer fair returns from the goods and services that they produce. Except that in this case there is no redress for the producer.”

Then he takes aim at the business houses that “commercialize the crime,” contending that on the shelves of such stores “books are simply cheapened.”

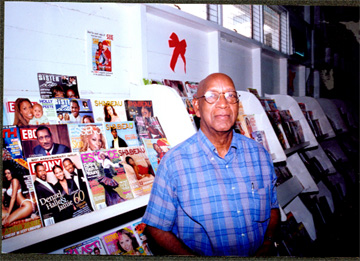

Hopkinson is the Director of the Guyana Reading and Research Centre, the largest book distribution facility in the country and his frustration over the plight of the bookselling industry is driven by much more than the limits of his own commercial success. He believes, he says, that there is an inconsistency between the exalted intellectual expectations of the society “that are frequently expressed by the powers that be” and the absence of support for “the business of reading.”

Hopkinson decries that fact that the recent rapid growth of the high street trading sector has found little room for “catering to the requirements of the intellect.” He believes that in much the same way as commercial marketing pursuits have helped to shape popular demand for new styles of clothing and new tastes in food, so too those marketing efforts could have focused on seeking to make reading more appealing to consumer taste. “The fact that books have now declined on the consumer’s scale of demands may have to do with less disposable income, but it also has to do with the fact that efforts to make reading more affordable, more appealing (are not being made). It appears to have been a deliberate choice and our declining level of literacy and corresponding increasing fashion consciousness reflects the outcome of that choice.”

Hopkinson says he is saddened that “having invested so much money and effort in providing the reading public with an excellent bookstore for years the proprietor of Universal Bookstore Mr Ovid Holder quietly called it a day about a year ago. Mr Holder made no secret of the fact that the disease of copyright had effectively killed his business. It would not surprise me if the premises that he occupied has passed to a trader in some familiar though perhaps less worthwhile commodity. No one seems to miss that bookstore.”

Hopkinson estimates that his own bookselling service sells approximately 1000 books monthly. “If you multiply that number by the handful of bookshops in the country you very quickly come to an understanding of the approximate size of our reading population.”

The reading habit, he says, disappeared several years ago beneath the weight of, first, television then the IT revolution “which provided quick reference alternatives to real reading. While Hopkinson concedes that the advent of television and the IT revolution amounted to considerable progress in the mass communication sector, it has also brought with it some retrograde trends. “Parents are now seeking to limit television time in order to try to get their children into the practice of reading and our schools and university are creating prohibitions on the instant reference research option which the internet provides. In the latter case the argument is that there are really no short cuts to reading a good book.”

Apart from the absence of a commercial marketing culture that focuses on the popularization of books Hopkinson places the blame for the reading crisis on what he describes as “a school system that has nurtured the decline.” In this regard he points to what he says has been “a failure to focus on the institutionalization of school libraries and to meaningfully infuse reading into the schools curriculum.” He believes that reading as part of the school’s curriculum can be encouraged through the creation of libraries that are supported by joint public/private sector efforts. “Of course gifts of computers to schools is a worthwhile thing, I believe, however, that it probably no less cost-effective for businesses to agree to create and sustain entire school libraries since libraries are in fact the infrastructure that can help to shape a reading-based curriculum.”

For all his disappointment Hopkinson says that there are signs that books may be making a commercial comeback. “When-ever I see parents browsing bookstores with their children or people looking for books to read I am hopeful. There is talk about a local publishing house and while that is only talk at this time at least it suggests that there are people in authority who are thinking about the business of books. CARIFESTA saw what appeared to be a resurgence of interest in books, HANSIB and a few other publishing houses saw to that. What we really need is a public/private sector commitment to the business of books, a set of circumstances in which policy positions can be married to private investment to restore an interest in reading by creating greater, more affordable access. It is, after all, an investment in those very objectives to which both our political leaders and corporate citizens say they aspire.”