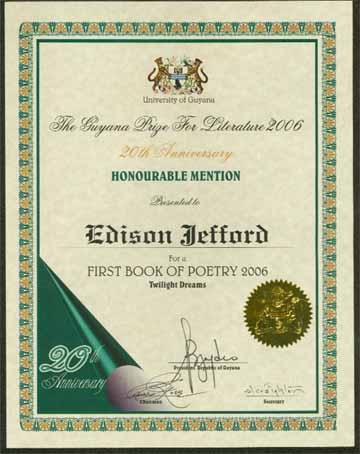

Guyana Review Editor Arnon Adams talks to 2006 Guyana Prize for Literature Honorable Mention awardee Edison Jefford

When I asked Edison Jefford where he felt his ambition as a poet would take him there was an arresting bluntness about his response. “I want to win The Nobel Prize for literature.”

it took a while before it finally dawned on me that he really believes that his ambition is achievable. He is, he says, “prepared for the journey,” which, on the basis of the available evidence, is really only just beginning.

In 2006 his collection of poems titled ………….was cited by the Judges in the Guyana Prize for Literature for Honorable Mention. He concedes that he was disappointed. “One is not entirely certain what the term Honorable Mention says about one’s work. Still, to have your poetry become worthy of recognition at the level of the Guyana Prize For Literature brings with it a considerable measure [of] satisfaction.”

Jefford is an English graduate of the University of Guyana and a sports journalist and we talked about the influence of language in his own personal outlook. There is, he says, “no essential nexus” between what he calls his “enduring passion for poetry” and his “pursuit of a career in journalism. “I suppose you can argue the language is the common vehicle of expression but that is as far as the nexus goes.“

His elaboration of the “differences between profession and passion,” focuses on what he calls “the functional differences” between the use of language in the respective pursuits of his journalism and his poetry. “There are taught rules that are applied to journalism. It is a functional thing which allows a strictly limited expression of self. Poetry is the opposite. It is the ultimate in the use of language as a vehicle for personal self-expression. The rules are rooted in the creative imagination. The poem is crafted in the mind of the poet and the lines and the sequences are very much a function of independent thought that conforms to one’s own pattern of thinking.” In essence, Jefford says that he does not believe that poetry can be taught “in the same way that you can teach a course in journalism. “The journalist is constrained by the paradigms of his profession. The poet is a far freer spirit.”

His elaboration drifts into language as a tool of self-expression. Of course language is the common vehicle. But there are vehicles and there are vehicles and once you contemplate the issue within that context it becomes easy to discover that language, like vehicles, can perform entirely different functions.” He refers to “the strictly functional role of language as a journalistic tool” as distinct from “the color, creativity and emotion that belongs in the language of poetry. I really do believe that the two function in different zones,” he says.

He idolizes Martin Carter. I believe that was fully deserving of the Nobel Prize. Martin Carter spoke to his audiences in language that painted pictures sufficiently vivid to be touched, I like to say that he painted his poems – crafted, perhaps, would be a more precise expression – so that every word, every line, brought its own particular significance to the poem. Carter comes from deep within. He really embodies the very essence of poetry.”

He concedes that his own looks to the Martin Carter legacy, “not stylistically, as such, but in terms of seeking within myself the creative intensity, the deliberateness of the great man. I never tire of reading his Poems of Resistance,” Jefford says.

His concerns about what he describes as “the creative condition of the Guyana society” centres around what he believes has been a cooling of the creative ardor in the local reading and writing cultures, “When I think of Martin Carter, particularly, I believe that we pay far too little attention to the continuity of our creative tradition, I remember spending four years at the University of Guyana doing a degree in English and not encountering Martin Carter there, That, for me, was a major disappointment.”

And while he believes that the Guyanese society continues to offer themes that a rich with poetic potential” he is disappointed that the local “market” for poetry is, in his view, not what it ought to be. “Here I do not use the term market in its mundane commercial sense. It is the intellectual market, the emotional market that is lacking. Our homes and schools really ought to be creating a breeding ground for a national appreciation of poetry. More than that we ought to be cultivating an interest in poetry through all the different things that you can do with it like celegrating our own outstanding poets; holding more national poetry competitions so that we can unearth the talent that is there and organizing recitals and readings at the community level. We do not do nearly enough to encourage the growth of that market.”

The practice of writing, Jefford says, “is constrained by the difficulties associated with publishing in Guyana,” His own first book of poetry was entered for the Guyana Prize in manuscript, a concession afforded local writers on account of the absence of publishing dacilities in Guyana. He believes, he says, that the creation of a local publishing house will not only encourage the emergence of more local talent but will also help to revive the culture of reading, “Our poets and our poetry are no less a natural resource than our minerals. What they offer is an opportunity for us to feel a sense of accomplishment, a sense of national pride. Poetry helps us shape our identity. Poetry affords us a creative identity that can play its own particular role in marketing our country to the world beyond our shores.”