I’ve studied, alas, philosophy,

Law and medicine, recto and verso,

And how I regret it, theology also,

Oh God, how hard I’ve slaved away,

With what result? Poor fool that I am,

I’m no whit wiser than when I began!

I’ve got a Master of Arts of Arts degree,

On top of that a Ph.D.,

For ten long years around and about,

Upstairs, downstairs, in and out,

I’ve led my students by the nose

To what conclusion? − That nobody knows,

Or ever can know, the tiniest crumb!

Which is why I feel completely undone. […]

I’m not bothered by a doubt or a scruple,

I’m not afraid of Hell or the Devil –

But the consequence is, my mirth’s all gone;

No longer can I fool myself

I am able to teach men

How to be better, love true worth; […]

Which is why I’ve turned to magic,

Seeking to know, by ways occult,

From ghostly mouths, many a secret; […]

So I may penetrate the power

That holds the universe together,

Behold the source whence all proceeds […]

to enlarge my soul to encompass all humanity

(Goethe, Faust, Part I)

Those lines articulate the spirit of the age. Take away the invocation of the occult, which, literally, is not necessarily a part of it, and they reflect the doubts, disappointment, loss of belief but belief in a controlling mystery yet to be found; a quest to find it and a need for change. They express a rejection of complacency, a rejection of the failure of the past and a looking forward to the discovery of that mystery and the dawning of the new day that it will bring. Such sentiments drive the present age, and have been the spirit of many previous ages repeated many times over.

The lines were written by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) the greatest German author of his time. They are spoken by Faust, otherwise known as Dr Faustus, the hero of one of the greatest works of German literature, the drama Faust Parts I and II (1808; 1832). It is in important ways different, but not too far removed from the sixteenth century play Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe, both taken from the same source but written in different eras with different stages of scientific advancement and different interests in religious enquiry.

In the legend Faust, the greatest scholar of his day has pursued studies in the arts, sciences and knowledge to their human limits. He becomes bored and impatient with the limitations, especially with theology and religion which have provided awareness of man’s weakness and powerlessness rather than the borderless knowledge of the universe that he craves. He rejects them and calls upon the devil to whom he sells his soul in exchange for 24 years of power beyond frontiers. The devil comes in the form of a spirit, the ‘arch-angel’ Mephistopheles with whom he traverses the earth, the heavens and all their secrets.

At the end Marlowe’s Faustus calls upon God for salvation from the devil’s deceit and eternal damnation but the play ends in moral ambiguity. In Goethe’s Faust the drama ends with the rescue of the doctor by God from final destruction; perhaps a reward for his progressive, revolutionary spirit and his intention to empower mankind.

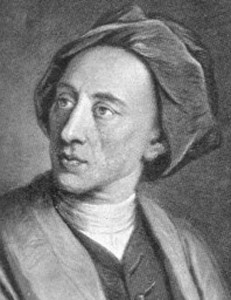

Goethe wrote in the age of Romanticism, a revolution against the earlier age of Reason. As always, the literature of those ages reflected the politics, the state of science and the social environments that they created. Faust’s speech comes after the Neo-Classical or Augustan age which was governed by reason; a sense of order and belief in a correct way in which things were to be done. The age patterned itself on the Classical era, in particular Rome in the reign of Caesar Augustus (27 bc-14 ad). The writers drew inspiration from the Roman poets of that time and verse forms were neatly ordered along the lines of heroic couplets and iambic pentameter. Alexander Pope (1688-1744) is held up as the premier Augustan poet.

Romanticism was a revolutionary response to Classicism with a preference for feeling over reason, natural expression over order. According to Matthews and Platt who describe the different literary eras in their Readings in the Western Humanities, “Faust is presented in this era’s Romantic language, which rejected historic religion but believed there was a mystery at the core of life. Thus Faust is revealed as obsessed with human ignorance.” He represents the feeling and enlightenment that the Romantic era advocated in opposition to reason. Pope’s long poem An Essay on Man actually sets out much of the kind of sensibility of his age and its approach to poetry and can be looked at as very much the kind of thing against which Romanticism led by poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge reacted.

Awake, my St John! leave all meaner things

To low ambition, and the pride of kings.

Let us (since life can little more supply

Than just to look about us and to die)

Expatiate free o’er all this scene of man;

A mightly maze! but not without a plan;

A wild, where weeds and flowers promiscuous

shoot,

Or garden, tempting with forbidden fruit.

Together let us beat this ample field,

Try what the open, what the covert yield; […]

Laugh where we must, be candid where we

can;

But vindicate the ways of God to man.

1. Say first, of God above, or man below,

what can we reason, but from what we know?

Of man, what see we but his station here,

From which to reason or to which refer?

Through worlds unnumbered though the God

be known,

‘Tis ours to trace him only in our own. […]

2. Presumptious man! the reason wouldst thou

find,

Why formed so weak, so little and so blind?

First, if thou canst, the harder reason guess,

Why formed no weaker, blinder and no less!

Ask of thy mother earth, why oaks are made

Taller and stronger than the weeds they

shade?

Or ask of yonder argent fields above,

Why Jove’s satellites are less than Jove?

(Pope, from An Essay on Man)

The poem is addressed to “St. John,” Pope’s patron Henry St John Bolingbroke, in the same way in which the Classical poets would address their muse. It is written in the typical heroic couplets and iambic metre and seems to establish man in his place in the universe and in society. Man’s existence relates to the order in society, all expressed in neatly ordered verse.