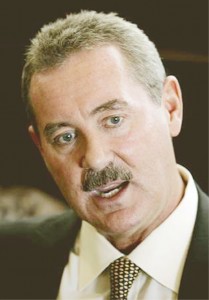

WASHINGTON/ST.JOHN’S, (Reuters) – U.S. law enforcement officials found Texas billionaire Allen Stanford in the Fredericksburg, Virginia, area yesterday, and served him with a complaint accusing him of an $8 billion fraud.

FBI spokesman Richard Kolko said the FBI acted at the request of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and that Stanford had not been arrested. The FBI gave few other details.

The whereabouts of the jet-setting 58-year-old tycoon who has luxury U.S. and Caribbean homes, had been the subject of intense speculation since he failed to respond to civil charges filed in Texas on Tuesday.

Stanford, two colleagues and three Stanford companies are accused of a “massive fraud” by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

U.S. federal agents raided Stanford Group offices in Miami, Houston and other U.S. cities earlier this week.

A law enforcement official said Stanford was making arrangements to turn in his passport.

The fallout from the SEC charges against the flamboyant, mustachioed financier and sports entrepreneur has rippled far beyond U.S. borders, prompting investigations from Houston to Antigua and Caracas.

Five Latin American countries have now acted against Stanford businesses, while Britain’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) is monitoring a possible U.K. link after media reports that Stanford’s books were audited in Britain.

The SEC accused Stanford in a civil complaint on Tuesday of fraudulently selling $8 billion in certificates of deposit with impossibly high interest rates from his Antiguan affiliate, Stanford International Bank Ltd (SIB).

The scandal, emerging hard on the heels of the alleged $50 billion fraud by Wall Street veteran Bernard Madoff, has again spooked international investors and sharply increased public distrust of investment plans.

In Caracas, the government of socialist President Hugo Chavez took control of Stanford Bank Venezuela, one of the country’s smallest commercial banks, to stem massive online withdrawals following the SEC fraud charges.

“The authorities were forced to take the decision to intervene, and there will be an immediate sale (of the bank),” Finance Minister Ali Rodriguez told reporters.

Another Andean nation, Ecuador, announced it was seizing two local Stanford units — a brokerage house and a fiduciary firm. “We will intervene to protect the interests of investors,” Santiago Noboa, the state regulator of the stock exchange in Quito, told Reuters.

Mexico’s banking regulator said it was investigating the local Stanford bank affiliate for possible violation of banking laws.

Peru’s securities regulator suspended the operations of a local Stanford unit.

ABC News reported Wednesday that federal authorities had been probing whether Stanford was involved in laundering Mexican drug money, but the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) said it had no current inquiry underway.

An initial review also revealed no past investigations, but officials were still checking, a DEA spokesman said.

Another federal law enforcement official said U.S. agencies previously had investigated suspected money laundering at Stanford’s offshore banks but did not find evidence warranting criminal charges.

As investigations into Stanford’s businesses widened, evidence emerged that his Stanford Group Co had been disciplined by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). the U.S. broker-dealer watchdog.

In November 2007, FINRA fined Stanford Group $10,000 for misleading sales literature that failed to prominently disclose risks, such as that the CDs were not issued by a U.S. bank and were not insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

The company was also fined $20,000 in April 2007 for not promptly forwarding customer checks from the firm’s retail brokerage operations and conducting a securities business without maintaining minimum capital levels.

In March 2008 the firm was fined $30,000 for research reports that violated a number of broker-dealer rules.

Mark Tidwell and Charles Rawl, former Stanford brokers in Houston, quit in 2007 over concerns that Stanford was lying to clients about returns.

Rawl told Reuters in an interview in Houston that when he confronted his managers about possible discrepancies in the performance of funds he was marketing to clients, he was told of ongoing discussions at the “highest level of management” about “whether or not we were going to let this sleeping dog lie.”

At a staff presentation in March 2007, management tried to conceal such discrepancies, Rawl said. “They tried to pull the wool over our eyes in a meeting.”

ANTIGUA UNDER SCRUTINY

Antigua and Barbuda Finance and Economy Minister Errol Cort said late Wednesday the twin-island Caribbean state was scrambling to shore up its banking system against the potentially devastating impact of the U.S. fraud charges against its biggest private investor and employer.

In St. John’s, a small Antiguan firm that Stanford identified as the auditors of his offshore bank said yesterday it had no information about ties to the tycoon.

The head of C.A.S. Hewlett & Co in the Antiguan capital said the firm’s former chief executive, Charlesworth Hewlett, was the only person with possible knowledge of a relationship to Stanford. Hewlett died on Jan. 1 at the age of 73.

“We are not privy to any information about any relationship with Stanford,” the firm’s head, who would identify herself only as Celia, told Reuters by telephone.

Britain’s Evening Standard newspaper had reported that Hewlett’s daughter Celia had taken on the responsibilities of the accounting firm from London after her father died.

Stanford’s personal fortune was estimated at $2.2 billion last year by Forbes Magazine. He holds dual U.S.-Antiguan citizenship, has donated millions of dollars to U.S. politicians, and has secured endorsements from sports stars, including golfer Vijay Singh and soccer player Michael Owen.

In Antigua, Stanford owns the largest newspaper and is the first American to receive a knighthood from its government.

Antigua has faced U.S. scrutiny in the past for alleged money laundering activities and operations by suspected Russian “shell” banks.

Jonathan Winer, a Washington lawyer and former State Department official in the Clinton administration, said that following a U.S. warning to Antigua in the late 1990s, consultants and lawyers working for Stanford took control of records of Antigua’s bank regulatory agency “to carry out a cleanup” of the suspect banks.

The local bank regulator objected, as did the U.S. government, Winer said. “The conflict of interest that we felt existed with using Mr. Stanford and his people to clean up the banking system was unique … it was bizarre and inappropriate.”

“One of the results of all this was that Antigua was put on a watch list.”

In response, Antigua implemented banking reforms requested by the United States, and the sanctions were lifted in 2001.