NEW YORK, (Reuters) – While accused hedge fund swindler Arthur Nadel sits in a Manhattan jail, Burton Wiand is busy seizing control of his assets — a 453-acre mountainside tract of land in North Carolina, several airplane hangars and a jumble of bank accounts.

Wiand, a Florida lawyer, is a court-appointed receiver, a job that has

become increasingly in demand in blockbuster fraud cases ranging from the Bernard Madoff scandal to the case against Texas tycoon Allen Stanford.

These appointees and their teams are third parties that step in and try to sort out the mess, and their efforts are crucial for investors who want to get at least some of their money back.

Receivers must juggle their search for assets with the oversight of employees at the companies they take control of, while providing updates to the court and dealing with panicked investors who may have lost their life savings.

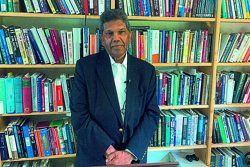

“If you do it well, you can feel like you’ve benefited some people,” said Wiand, the receiver in the Nadel case in which a 76-year-old Florida money manager is charged with bilking clients of as much as $300 million.

But “it’s very disappointing to get into these things and see what awful things people have done to others. It’s depressing at times to see how investors have really been hurt.”

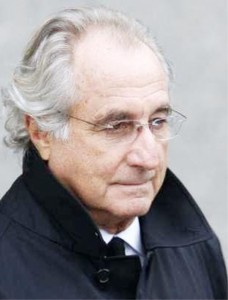

The role of receiver, or in the Madoff case a trustee liquidating the accused swindler’s brokerage firm, is typically assigned to lawyers, accountants or banking experts. They are financial sleuths who try to unearth any remaining assets that could ultimately be converted to cash and returned to the former customers of a collapsed firm. They often must look far afield — especially when dealing with globe-trotting wealth managers who have accumulated all kinds of luxuries. Madoff, for instance, owns properties in Manhattan, New York’s Long Island and France, while Stanford has property in the United States and the Caribbean. Receivers in financial fraud cases typically step in at the request of regulators. Their first step is to seize control of a company and change the locks on the doors, often sending in forensic accountants to scour computer records.

They are not government officials. But receivers often seem like law enforcement officers because they can swoop in unannounced, take possession of premises and at least temporarily manage the employees, who they often tell not to return to work.

“We seize things, tell people to step away from their computer terminals — that way they don’t have a chance to touch and disturb anything,” said Robb Evans, who has served as a receiver or other court-designated role many times. “We come in and basically become the chief executive officer of the operation.”

Evans was appointed last month as the temporary receiver in a case against Paul Greenwood and Stephen Walsh, New York money managers for pension funds and universities arrested and charged with stealing more than $500 million from client accounts.

Regulators and prosecutors say the men stole from investors to cover trading losses and used the money for personal expenses, including the upkeep of a horse farm and the purchase of an $80,000 collectible teddy bear. Evans said his team has taken control of “substantial assets” linked to the case, but “without knowing the likely claims against those assets” the outlook for the net recovery is unclear.

TOUGH ROLE

TO PLAY

Decisions made by receivers, who say their first and foremost job is to lock down assets, are not always popular.

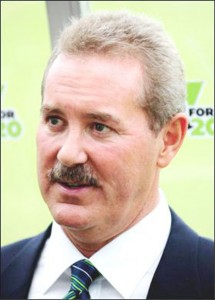

In the Stanford case, receiver Ralph Janvey angered some investors by freezing their brokerage accounts at Stanford Financial Group — portfolios that were not at the centre of fraud charges. A judge later unlocked some smaller client accounts at Janvey’s request.

Trustees and receivers say they must give all former customers equal treatment, which can make some people unhappy. One former trustee said dealing with bilked investors was one of the hardest aspects of her job.

“You have to sit face to face with them and tell them that you have to make life fair for everyone and that may mean more pain for them,” said New York attorney Aurora Cassirer.

The Madoff firm’s trustee, lawyer Irving Picard, recently faced a group of angry clients who peppered him and two colleagues with questions.

Some customers said they feared Picard would sue them to try to recoup past profits. Others denounced the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which had looked into Madoff over the years but never pinpointed the purported fraud U.S. prosecutors say he confessed to in December.

“I think this is unfair. We are the victims, not only of Madoff,” said retiree Raymond Spungin.

In response, David Sheehan, one of the trustee’s colleagues told Spungin: “There is nothing we can react to. I think it is good that the public hears it and the press hears what you have to say. I wish we could react to it, but we can’t.”