In November last year the Schomburgk Pavilion and pond were officially launched in the Botanic Gardens. The pond contains plants of the Victoria amazonica lily, which in this country still tends to be referred to by its original name, the Victoria regia. This enormous water lily was brought to world attention by the German Robert Schomburgk, who first encountered it high up the Berbice River on January 1, 1837 when on his travels here for the Royal Geographical Society. He was not the first European traveller to see this empress of the water lily family, but his seed samples and the publicity which attended his explorations meant that his name became indelibly associated with it.

The pavilion takes its name not just from Robert Schomburgk; it also commemorates his brother Richard, who accompanied him on several of his second set of expeditions to survey the boundaries of what was then British Guiana between 1841 and 1844 for the British government. Richard was a botanist of considerable talent, but is best known in this country less for his botanical work, than for the first two volumes of his three-volume Reisen in Britisch Guiana in den Jahren 1840-1844 (1848), which were translated into English as Travels in British Guiana by the indefatigable Walter Roth. Excerpts from these translations have been published in the Guyana Review in recent times.

Roth, who translated the work of Dutch historians like PM Netscher as well, to while away the evening hours in the bush, was one of the pioneers here in the field of anthropology. Interestingly, he had come here from Australia, while Richard Schomburgk was to make the reverse trip, settling in the Antipodes a few years after leaving here, and building up a remarkable botanical collection in Adelaide as the director of that city’s botanic garden.

And just as Richard Schomburgk was commemorated here last year, it was the turn of

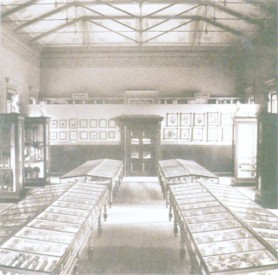

Adelaide to remember the botanist this year, and to celebrate his contribution to South Australia by refurbishing his Museum of Economic Botany. With a grant from the Australian government, it was re-launched at the end of May with an exhibition called ‘Harvest,’ which will be open to the public until August. According to the exhibition programme, Richard Schomburgk is regarded as “the father of the grain industry in South Australia.”

In the nineteenth century, however, what particularly attracted visitors to the Adelaide Botanic Garden was Victoria House, which as its name suggests provided a home for the Victoria regia lily, and a direct link to Guyana, from where the seeds came. In general, it could perhaps be claimed that Richard Schomburgk’s experience with collecting specimens here, and the scientific help he received on his return to Germany in classifying these, laid the groundwork for his remarkable contribution to the city of Adelaide, and to South Australia as a whole.

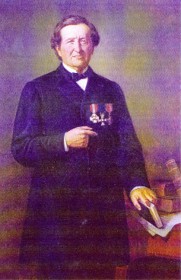

Richard Schomburgk was born in the small town of Freyburg, Germany, in 1811, and started out his professional career as a gardener in a place called Merseburg. After an interlude of three years’ military service, he worked in the gardens of the King of Prussia at Potsdam for five years, and according to his biographer, Pauline Payne (The Diplomatic Gardener), although he gained experience in the propagation and care of various plants, shrubs and trees, there is no evidence he received any formal training in botany there.

Nevertheless, that does not appear to have been an impediment for someone like Richard

Schomburgk, who was endowed with an inquiring mind and an industrious disposition, and his obvious talents made an impression on the great German explorer, Alexander von Humboldt. It was through the latter’s intervention he was persuaded to accompany his brother Robert to British Guiana. As mentioned above, Robert was retained by the British government to survey the colony’s boundaries, but Richard’s commission was of a different order and emanated from a different source, namely the Prussian government, which asked him to collect specimens of flora and fauna for the royal museums and the Botanical Gardens in Berlin. It was at this point, says GAC van Dam (The Guyanan plant collections of Robert and Richard Schomburgk), that Richard received some specific training in the collection of specimens from Berlin’s Museum of Natural History.

Richard Schomburgk arrived in early 1841 in Georgetown, and not long after he contracted yellow fever; he recovered, however, and eventually in April, all was ready for the first expedition to the Barima and Cuyuni. The second expedition began in December of that year, and took the brothers to the source of the Takutu River, and following that, in September 1842, to the Roraima region. With Robert already back in Pirara (he had been there before), in 1843 Richard set out to meet him for a sojourn in the Rupununi.

Payne relates the problems Richard had in preserving his botanical specimens, and quotes him as writing:

“How I wished that some of the gentlemen who shrugged their shoulders in so strange a manner when I related the difficulties that had to be contended with in the preservation of my specimens, and informed them of the terrible losses entailed by an adverse climate in spite of all the sleepless nights during which… I had to dry my paper at the fire – how I wished that the critics might learn from their own experience what it meant, with the means at my disposal, to make collections in the tropics in thick and impenetrable forests… And yet, notwithstanding the heavy losses, preserve as much as I did for the scientific societies at home.”

And the collection which he managed to preserve – flora, fauna and ethnographic items –

was extensive. In fact it was so large, that he could not return home with Robert on the steamer, but had to travel with it – both living and dead specimens – on a merchant vessel. Payne has described the journey. She says that accompanying him across the ocean (among other things) were “an eleven-foot boa constrictor and two other snakes, around six feet long. He took earthworms to feed the electric eels and changed the water of their wooden tubs daily, but, despite this, his last two specimens died as the ship reached the English Channel.”

Where some of Richard’s plants were concerned, Payne has this to say: “He had constructed a frame to store his palms and orchids in the ship’s long boat, only to find that they were badly affected by the weather conditions. The next step was to move boxes of plants into his cabin, but here they were attacked by the ship’s mice and rats. While mice and rats proved useful for feeding his menagerie, over the eight-week voyage his creatures died daily – and were duly fed to those remaining. Transporting the delicate plants required more of the wardian cases that provided temperature and moisture control. Unfortunately, he had only been able to afford two of these. Of around two hundred palms, only sixty arrived safely in Berlin, but he had better luck with his precious orchid collection. Three hundred specimens survived, covering sixty species.”

On his return home, Richard Schomburgk concentrated on writing his Reisen… the third volume of which deals with the flora and fauna of this country. (Unfortunately, it was not translated by Roth.) For this volume he took advice from some of the great natural scientists of the day, and Payne says that in his obituary, it was described as his most important work on taxonomy. In 1849, the year after it was published, he emigrated to Australia, where he started a farm and a vineyard in conjunction with his brother, Otto.

Richard became the curator of the Gawler Museum in 1860, and five years later he was made Director of the Adelaide Botanic Garden. He was not its first director, but he was certainly the one who established its reputation, not just in Australia, but worldwide. Van Dam lists his achievements at the Adelaide gardens as including the introduction of heating to the orchid house to improve the quality and variety of orchids cultivated there; building the Palm House and the Fern House, not to mention the glasshouse, christened the Victoria House because, as said above, it accommodated Guyana’s Victoria regia lilies. And then, of course, there was the centerpiece, the Museum of Economic Botany, whose reopening this year and current exhibition, as already mentioned, celebrate Richard Schomburgk’s contribution both to the garden, and to the agricultural economy of that region of Australia.

Writing in the introduction to the catalogue of the ‘Harvest’ exhibition, the current Director of the Adelaide Botanic Garden, Stephen Forbes, says that the museum “was the [Australian] government’s first significant investment in a theatre to engage colonists in the opportunities to exploit new food, fibre, timber and medicinal plants for their own wealth – and the wealth of the colony and Britain.” In the process, he writes, the Adelaide Botanic Garden “literally” planted South Australia as a colony.

Van Dam says that Richard was probably the most “notable importer of plant material to Australia in his days,” and that by 1878 Adelaide had one of the world’s largest living plant collections, with 8,500 specimens listed in the catalogue.

Richard Schomburgk never retired, and even although he suffered from gout which caused him considerable pain, he could still be found working in the herbarium in his final years. He died in office in 1891 at the age of 79.