Part 2

By Tarron Khemraj

Last week we underscored that the concept of macroeconomic stability – which is often touted as a success by IMF reports and pro-government commentators – is at best tenuous. Last week’s column examined several indicators of macroeconomic stability and we found mixed evidence of stability; in particular, the inflation rate has re-stabilized since 1993 (although at a lower average) at around 7% compared with the 1971 to 1987 average of approximately 14%. Therefore, Guyana has never really experienced the kind of inflation (or hyperinflation) experienced by many countries in South America and Latin America. We saw a tendency for the external debt burden to ease. However, the future sustainability of the external debt situation will hinge on production transformation, which we will take up in this week’s column.

We also saw that the current account deficit (on the balance of payments) has widened in recent years. The latter suggests a weak performance vis-à-vis the rest of the world and as such the talk of macroeconomic stability does not rest on sound macroeconomic fundamentals. After all, the current account balance is a demonstration of the production capability of a country. For an economy like Guyana that does not possess a major global reserve currency, it is important to produce and sell goods and services to the rest of the world so as to earn scarce foreign exchange, which is then used to purchase critical capital goods and technology for the process of economic growth. However, we have noted last week that in spite of large inflows of foreign aid and remittances, the current account is running a deficit of approximately 25% of GDP in recent years. In addition, Guyana is known to receive the highest percentage (43% in 2007) of remittances relative to the size of GDP in the Caribbean and Latin America (see SN article of March 17, 2008 in local news). The latter, therefore, does not seem to me to be rooted in sound macroeconomic fundamentals. Something is fundamentally wrong with the term “sound macroeconomic fundamentals” when a country is living off the life support of the international financial institutions and remittances are crucial for subsidizing domestic private household consumption. I will use this column to examine what is wrong with this interpretation of sound macroeconomic fundamentals. We will see that there have been minor changes in the structure of production or source of GDP in Guyana. The latter is in keeping with a continual argument that I make – that is we can only speak of sound macroeconomic fundamentals when Guyana starts to make products that are higher up the global hierarchy of products; in particular, goods with high income elasticity (that is the demand for the country’s products rise concomitantly as world income increases – energy products and tourism clearly fit this profile).

Guyana’s economic growth since 1961

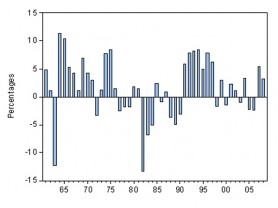

However, before presenting the data on the structure of Guyana’s GDP, let me take some time to examine the historical pattern of Guyana’s GDP growth since 1961. Overall, one of the first things to notice from Figure 1 is the volatile nature of Guyana’s GDP growth. By volatile I mean the large swings and jagged nature of the bars in the chart. This is typical of economies that depend on primary resource extraction and low productivity agriculture. The unstable nature of GDP growth cannot be seen as representing macroeconomic stability. But in order to make proper comparisons, we would need to analyze this volatility relative to other economies. That could be the subject of another column.

Figure 1, Guyana’s annual GDP growth – 1961 to 2008

Data source: World Development Indicators, electronic access and IMF country reports

In the period 1961 to 1966, Guyana’s GDP grew at an average of 3.44%. In the Burnham years from 1967 to 1985, GDP grew at an annual average of 0.51%. In the Hoyte adjustment years – 1986 to 1992 – GDP grew at an average of 0. 31%. In the Jagan years – which enjoyed substantial positive economic inertia from the Hoyte reforms – of 1993 to 1997 GDP grew at 7.17%. Since 1998 GDP grew at an annual average of 0.86%.

The structure of GDP

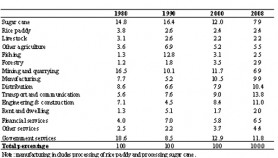

Table 1 presents the percentage share of GDP of each production sector in Guyana. Moreover, the table reports selected years. The reason for this is because structural shifts in the economy take a long time to occur. Therefore, it is sufficient to report only a few years rather than each year – after all, this column is concerned with the long-term. Each sector’s output was divided by GDP at factor cost to give the relative share.

One important observation is the non-traditional agriculture (or other agriculture in Table 1) rise from 1980 but then level off since 1990. The fishing sector’s percentage has shown dramatic signs of decline since 1990. Livestock – a sector with tremendous potential – has remained flat over the decades. The forestry sector – which accounts for a small share of GDP – has shown some tendency of increasing its share in GDP.

Table 1, Structure of Guyana’s GDP – selected years

Data source: Bank of Guyana Annual Reports and Statistical Bulletins (various years)

Mining and quarrying – which includes mainly bauxite and gold – have declined. Of course, some of this is related to OMAI, which is no longer pursuing large scale mining in Guyana. But that is expected as gold mining is just another example of a sector susceptible to diminishing returns. There is only so much you can mine and a country without a conscious industrial policy to process some of these materials at home will enjoy less of the production returns and extracted wealth. Furthermore, Guyanese have long recognized the need for an aluminium smelter, which would inject a larger percentage of the extracted wealth into the domestic economy, but nothing was ever done. One day the bauxite will finish – yet another classic case of diminishing returns – and Guyanese would still be poor. Of course, there is more gold and possibly oil and large scale mineral extraction is still possible, thereby increasing the percentage contribution of this sector. But is mineral extraction all that the policy makers can visualize?

On the other hand, engineering and construction and transport and communication have shown clear signs of improvement. So too have been distribution services. However, financial services – which have tremendous wealth creating potential – have remained flat and account for a small share of GDP. The same can be said for other services. It is well known that the service sector is very important for economic development. For instance, the service sector like banking (commercial and investment banking), insurance, fund management, brokerage services, financial analysis and advice, stock and bond trading, etc, are known to employ people who are highly skilled – thus the pay and productivity are high in these activities relative to the petty service industries.

Overall, the service sectors have tended to assume a larger share of GDP. However, we have to be careful with the interpretation here. For example, if distribution services – which have increased – are focused dominantly on the import and retail trade, then this will not have a favourable effect on long-term structural transformation. However, if it represents subsidiaries of local manufacturers such as Banks DIH and DDL, etc, then that is obviously a good development as these firms are developing the mechanism to distribute domestically manufactured products. Therefore, as they say, the devil is in the details.

Sugar production, as a percentage of GDP, has shown substantial signs of decline. On the other hand, rice paddy production has remained flat. However, the decline in sugar cane harvesting is not a good thing for several reasons. First, the new Skeldon sugar factory needs large quantities of sugar cane to process into sugar so as to achieve the level of economies of scale required to reduce unit production cost to buffer the industry against the EPA (Economic Partnership Agreement – between the Caribbean and the European Commission) price cuts. Second, large scale sugar cane processing is essential to generate the 15MW of electricity for the Skeldon plant to supply to the national grid.

As I have noted in my donkey-cart economy letter, I believe this investment in a new sugar factory was not an optimal use of the country’s scarce resources. Nevertheless, it is now a sunk cost and cannot be recovered and we can only hope for the best. The latter brings us to the third reason why it is important to boost sugar cultivation and not waste the existing sugar cane field infrastructure. The country is throwing away a good chance to pursue a renewable energy (ethanol and bagasse) industrial strategy and save the West Berbice, East Demerara and West Demerara sugar estates. Many jobs can be saved and created in the process. Also, a renewable source of energy – ethanol and bagasse – is developed, thereby boosting the manufacturing and energy sectors. In addition, the strategy saves (and/or earns) significant amount of foreign exchange over time.

The manufacturing percentage has shown some signs of improving since 1990. However, most manufacturing, according to the Bank of Guyana reports, are really the processing of sugar cane into sugar and the processing of rice paddy into more polished rice. Therefore, the manufacturing sector has remained rooted in low productivity activities and as I have noted above sub-optimal commodities like sugar.

A conscious industrial policy framework by the government in collaboration with the private sector is needed to upgrade this critical sector for economic development. Indeed, there is a substantial literature in economic development linking manufacturing growth and GDP growth on the one hand, and labour productivity (essential for higher future living standards) and growth of the manufacturing sector. These relationships are known to heterodox economists as Kaldor’s growth laws (Yes the same Nicholas Kaldor who was invited to Guyana by Dr. Jagan to help reform the tax system).

Conclusion

This column argued that Guyana’s production structure has remained rooted in low productivity activities – products that have passed their prime decades ago and are susceptible to diminishing output returns. Moreover, a higher sustained living standard for the Guyanese masses is dependent on increasing output per worker – the simple measure of productivity. Therefore, the argument that Guyana has sound macroeconomic fundamentals is at best tenuous. Most likely this argument stems from the very narrow stabilization and poverty reduction mandates of the IMF and World Bank. But in the long-term sound macroeconomic fundamentals must be rooted in production transformation and not aid and remittances that promote a false sense of success among the population and pro-government commentators.

Next column I will critically outline the nature of economic policy in Guyana and suggest alternatives for the future. We will examine the difference between short-term stabilization and palliative poverty reduction policies (which are really the mandates of the IMF and World Bank, respectively) and long-term production strategies, which are the mandate of the government working with private risk takers and investors.