Bookshelf

By Ronald Austin

George Padmore: Pan-Africanist Revolutionary edited by Fitzroy Baptiste and Rupert Lewis. – Kingston, Jamaica : Ian Randle, 2008. – 279 p.)

At this distance in time I cannot recall who placed a copy of the book Pan-Africanism or Communism in my young hands. Its contents were impressive. The book assumed greater value when I realised that the writer was a West Indian. It was in fact a great help in my search for ideological roots and identity. And the intellectual tools being provided were coming from a regional compatriot and not one of the more celebrated European writers. The trouble was I could not find out anything of significance about the writer, George Padmore. What there was, was stimulating, but meagre: an essay by his celebrated contemporary, CLR James. But it was impossible that someone who had contributed so much to the political thinking of the region, the freedom of African states, and the political condition of colonial mankind could remain forgotten for very long.

An academic conference was held at the University of the West Indies, St Augustine Campus, in October 2003 to redeem this seminal West Indian thinker and make Padmore better known beyond the single biography of him by James Hooker entitled Black Revolutionary: George Padmore’s Path from Communism to Pan Africanism. Now however there is George Padmore: Pan-Africanist Revolutionary consisting of ten academic papers which explore various aspects of Padmore’s life: his work as communist, his career as an organiser, his role as a Pan-Africanist, his ambiguous relationship with Marcus Garvey and his role as an adviser to Kwame Nkrumah, among other subjects. I cannot say that my hunger to know more about Padmore was satisfied. Maybe it is because I am from the old school; I like to know how historical figures appeared to other men.

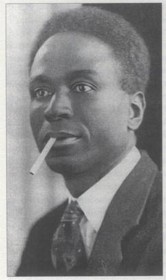

This collection of essays is good at analysing Padmore’s political, economic and Pan-Africanist thought, however, it is Padmore the man that I find most attractive. In the eighth paper written by Rupert Lewis, ‘George Padmore: Towards a Political Assessment,’ a figure of human dimensions emerges. Lewis quotes Peter Abrahams, the South African and Jamaican writer’s impression of Padmore:

“Padmore was a man to whom the politically inclined among the blacks in Britain gravitated. He had a London County Council flat on Morningside Crescent in Camden Town. It was up two flights of stairs, a dark place with small rooms leading off a tiny entrance space. I think there were three doors… and what I guess to be the largest room was where Padmore worked and met visitors. George Padmore seemed taller than he was because he held himself so ramrod straight. He was thin, austere, always neatly dressed, with crease lines in his usually dark trousers and spotless white shirt under jacket and tie. His shoes always shone. I cannot remember Padmore without a jacket and tie. I knew him for many years, but I never saw him in an open neck shirt.”

This reads like a description of a tropical Stafford Cripps, but it captures the disciplined  manner in which Padmore lived his life and did his work. It was only such discipline which enabled him to do prodigies of work even though he was a man who suffered from ill health most of his life. Lady Cunard who knew Padmore very well said his “capacity for sheer, lengthy hard work was very great, and his knowledge seemed to me immense.” It should be remarked here that Padmore’s intellectual confidence made him look down on Marcus Garvey. He regarded Garvey as a bit of a charlatan and was hesitant to revise his views of him, even when it was proven that Garvey had been right in many instances. On the other hand, Padmore seemed to accord great respect to the other founder of Pan-Africanism, Dr Du Bois.

manner in which Padmore lived his life and did his work. It was only such discipline which enabled him to do prodigies of work even though he was a man who suffered from ill health most of his life. Lady Cunard who knew Padmore very well said his “capacity for sheer, lengthy hard work was very great, and his knowledge seemed to me immense.” It should be remarked here that Padmore’s intellectual confidence made him look down on Marcus Garvey. He regarded Garvey as a bit of a charlatan and was hesitant to revise his views of him, even when it was proven that Garvey had been right in many instances. On the other hand, Padmore seemed to accord great respect to the other founder of Pan-Africanism, Dr Du Bois.

Padmore’s immense knowledge and capacity for analysis laid bare the evils of colonialism and was the basis for a considerable number of books, including the impressive Pan-Africanism or Communism and How Russia transformed her Colonial Empire. His publications were so influential in the colonies that some of them were banned by the authorities. At one time Padmore wrote for at least half a dozen newspapers in different parts of the world, quite a few of them being very well known, such as the Moscow Daily News and the Chicago Defender. In Professor Anthony Bogues’ paper entitled ‘CLR James and George Padmore’ he quotes the former as estimating the work of Padmore at this period: “What Padmore did between 1930 and 1935 was organize and educate the negro masses on a world scale in the theory and practice of modern politics and modernism.”

The most riveting aspect of George Padmore’s life was his ascendancy in the Communist International and his subsequent break with Moscow. The book appears deficient in explaining how a young student from the Caribbean, having changed his name from Malcolm Nurse to George Padmore, could in five years, as a member of the American Communist Party, rise to the level of an official in the Profintern or the Red International of Labour Unions. Padmore must have been a trusted member of the Communist International to have risen so rapidly in the hierarchy of that organisation. That he was a genuine and dedicated communist is not hard to believe. For as Professor Teelucksingh has explained: “The Russian Revolution had considerable lustre and ideological appeal to radicalized colonial subjects who supported the political ideas in Lenin’s writings on national and colonial questions.” Padmore also travelled extensively and secretly in Europe and Africa on political missions.

But it seems in retrospect that Padmore’s fierce opposition to colonialism brought him into conflict with the Kremlin. He regarded communism as a tool for bringing an end to imperialism and colonialism around the world. For the new czar in the Kremlin Comintern was an important instrument in the pursuit of the national interest of the Soviet Union. When Stalin decided that the communist parties and organisations must temper their criticisms of British and French colonial policy in order to forge an anti-Nazi alliance with the West, Padmore rebelled.

But his break with the Kremlin was as risky as it was principled. For it involved underground connections in the dangerous world of the ideological conflicts of the period. Stalin was master of the Kremlin and he did not brook opposition to his rule or his orders. Yet Padmore stood his ground and went on to make a significant contribution to the anti-colonial revolution. But he had understood Stalin’s sudden change in policy. Professor Lewis in the paper already mentioned quotes him as saying: “The Russians like the British ruling class have no ‘permanent friends, nor permanent enemies but only permanent interests’ namely the survival of the Soviet Union.” Stalin was a man not easily denied. Padmore had to bear the attacks from his former colleagues in the Kremlin.

Our own PPP played a role in this propaganda exercise. In 1973 the PPP publicised a pamphlet written by the Chairman of the American Communist Party, Henry Winston, entitled Padmore, the ‘Father’ of Neo-Pan-Africanism. The title speaks for itself. It was an attack on Padmore and it was widely circulated among the leftist parties in the Caribbean. But it did not find resonance and Padmore’s reputation endured. The break with the Kremlin was a lasting experience as CLR James has explained in one of his essays on Padmore which was publicised in Writings, edited by Anna Grimshaw. After his experience with the Soviet Union Padmore would ensure that any movement to which he belonged would operate independently and serve the interests of the colonial masses seeking freedom from their bondage.

Padmore was now free to pursue his Pan-Africanist agenda and work in the open. It must be noted that this was not a narrow agenda. It would not be bound to the unbridled capitalism of the West or the doctrinaire communism of the East. This Pan-Africanism transcended race and gender and sought the liberation of workers throughout the British Empire. Finally, it envisaged the unification of the African continent. It is interesting that although he had broken with the Kremlin, he would use the language of its doctrine, and the extensive contacts developed during his period with the Comintern in his fight against colonialism. There is a further contradiction. Padmore would use his considerable influence to persuade colleagues against embracing the communist faith. Arthur Lewis is quoted in this volume that if there were very few communists in Africa and the Caribbean this must be attributed to Padmore.

Padmore had long studied the colonial question and now he devoted his considerable energies to the liberation of Africa. The event which triggered his activities in this regard was the invasion of Ethiopia. As something of an organising genius who had arranged several conferences as a member of the Comintern, Padmore established the International African Services Bureau. Initially mobilising support for Ethiopia, the IASB would become the spearhead of Pan-Africanism. Its triumph would be the Manchester Conference of 1945, when an entire generation of anti-colonial fighters assembled: Kenyatta and Nkrumah, Peter Abrams and Ras Makonnen.

The Manchester statement was advanced even by today’s standard and was a personal triumph for Padmore. Professor Hakim Adi in his paper, ‘George Padmore and the 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress’ assessed his role in these terms: “The 1945 Congress shows that Padmore had extraordinary organisational skills, formidable journalistic talent, and was able to put together political programmes with clarity and precision.” Incidentally, the Manchester Conference called for a Federation of the British West Indies and made several remarkable proposals for the development of the region. It is generally agreed that the conference led to the independence of Ghana. It was the high point of Padmore’s career. He became adviser to Nkrumah and at the time of his death in 1958 he was organising a conference aimed at the unification of the African continent. While he was inclined to scale the heights from Africa, Padmore showed no inclination to return to the region he left in 1924; in fact, he did not.

Yet one of the central points about this book is that Padmore is virtually unknown in the Caribbean except to historians and pan-Africanists. This says more about our region than it does about the brilliant Padmore. I have to agree with Professor Anthony Bogues: “What the work and ideas of George Padmore represented was a radical challenge to Marxist thought and practice. That today Padmore still remains a relatively obscure figure suggests that we still have a lot intellectual work to do in the quest for full decolonisation.”