Bharrat Jagdeo’s elevation to the presidency ten years ago was widely welcomed. There were hopes that the seventh president would restore national unity and faith in the future. What happened?

In the beginning, Bharrat Jagdeo’s conciliatory gestures, youthful ardour and openness promised to resolve the ancient feuds between the People’s Progressive Party-Civic and the People’s National Congress-Reform. The young president, then only 35 years old, was expected to purify the poisoned political atmosphere that was polluted by the acrimony between the outgoing President Janet Jagan and Opposition leader Desmond Hoyte. His big idea was to reunify the fractured nation.

Janet Jagan’s troubled 19-month tenure had been beset by problems. The sequels to her 1997 election were urban disorder and the adoption of a series of measures − the Herdmanston Accord; Ulric Cross’s ‘forensic audit’ of the elections results; the St Lucia Statement; and Maurice King’s ‘good officer’ dialogue process – aimed at restoring public order.

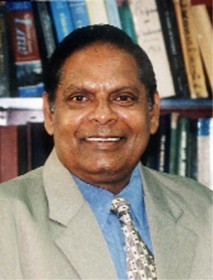

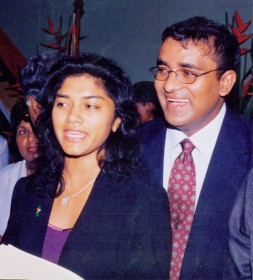

Jagdeo came to the office with abundant advantages of a groundswell goodwill and popularity. A Russia-trained economist, his business-like approach to ‘summit’ meetings with the private sector; quick acceptance of the Public Service Arbitral Tribunal’s recommendations; restart of the stalled PPPC-PNCR dialogue process; taking Cabinet meetings to the regions; visits to flood-hit areas and willingness to meet citizens and groups everywhere evinced the energy his predecessor lacked. Together with his attractive wife Varshnie, he seemed to be the right man in the right place.

Coalition

The Jagan coalition that he inherited in the cabinet, the central committee of the People’s Progressive Party and in the country at large had been composed over a long period to embrace virtually all sectors of opinion and cultural interests. The ‘civic’ component was still embedded in the administration. Jagdeo himself − without the impediment of ideological inflexibility of his predecessors − seemed best suited to guide his party and lead the nation at that historical juncture. The coalition that had enabled him to move to the centre of the political stage, however, was ill-suited to the design he had in mind.

The Jagdeo coalition would be very different from the Jagan coalition. When he became president in the late-1990s, the country was fed-up with fifty years of socialist ideology and yearned for fresh ideas. He had none. He was a centralist and populist; nationalist and regionalist; pro- state enterprise and pro-private enterprise; pro-Russia and pro-America, all at the same time. In domestic affairs, Jagdeo had no desire to emulate Cheddi and Janet Jagan. The last thing he wanted was to extirpate Forbes Burnham’s constitutional stance or Desmond Hoyte’s economic style. His intention was to assimilate them into his own management methodology of the political economy.

In order to consolidate his coalition and reinforce his position in the framework of the PPP’s

central committee’s ‘democratic centralism,’ Jagdeo had to deal with the ambitious Khemraj Ramjattan who was both a competitor and a critic. A pretext was found when certain claims were made about an incident that occurred in the central committee in January 2004. In short, the central committee rallied around Jagdeo and Ramjattan was expelled.

By the start of 2009, the coalition was secure. Apart from Prime Minister Samuel Hinds, Jagdeo had seen off every other ‘civic’ member from the cabinet; increased the number of ministers who, like himself, were alumni of the People’s Friendship University of Russia – the former Patrice Lumumba University – and reduced the average age of ministers to below 50 years. In the wider society, he ridiculed Georgetown’s old business elite as ‘fossils’ of a bygone era and embraced a generation of the nouveau riche in his coalition.

Jagdeo’s fatal flaw was that, unlike all his presidential predecessors, he knew no history – of the citizens, country, territorial controversies and the Caribbean region. Much worse, he seemed to have no sense of history and simply did not think historically. As a result, although he had some successes, many of his initiatives failed to achieve their objectives and, in some cases, did damage which will take years to repair whenever he leaves office.

Security

Nowhere was Jagdeo’s lack of a sense of history more evident than in his failure to fully comprehend the strategic territorial concerns of Suriname and Venezuela. In the wake of the humiliating eviction of the Guyana-licensed, Canadian-operated CGX petroleum exploration platform from Guyana’s waters, he presumed that he could personally negotiate a complex, 60-year-old territorial controversy with the better-informed Surinamese President Jules Wijdenbosch who was briefed by an efficient Foreign Ministry. He failed.

In the final analysis, acting under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Guyana filed a petition to the Convention’s arbitration tribunal on 24 February 2004 to have the maritime border with Suriname delimited. The tribunal published its award delimiting the maritime zone on 20 September 2007, largely along the lines of Guyana’s claim. This turned a diplomatic disaster into one of Jagdeo’s most significant strategic successes.

Jagdeo, similarly, seemed to have no grasp of Venezuela’s historical intransigence on its territorial claim. He underestimated Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez’s resolve to veto the Guyana Government’s agreement with Beal Aerospace Technolo-gies to construct a satellite launch facility in the Barima-Waini Region. Guyana was also forced to suspend offshore exploration rights to two American companies – Century and Exxon – after Venezuela objected. All three companies subsequently withdrew.

Internal security also degenerated during Jagdeo’s watch. The main causes of the upsurge in

criminal violence were the failure to suppress the dangerous narcotics trade and its associated money-laundering, the ballooning of all forms of contraband including gun-running, fuel-smuggling and people-trafficking; and the increasing incidence of graft which punctuated his presidency. Occurring even under his own eyes at the Office of the President and the Ministry of Finance, graft among public officers raised real questions about the administration’s inability to see the connection between transnational crimes and internal security and its own capacity to stamp out corruption.

Public safety was already in a parlous state at the start of Jagdeo’s presidency in 1999 when criminal violence, much of it directed against businessmen, started to surge. Ronald Gajraj had been appointed Minister of Home Affairs in January 1999 but his approach to the Guyana Police Force and public safety was ill suited to the long-term suppression of serious crime, to say the least. Extra-judicial killings by police special squads escalated, as shown by the Guyana Human Rights Association’s tally of deaths by police shootings. As drug-smuggling increased, drug lords and drug gangs also made their appearance.

Rather than tackle crime by eradicating drug-smuggling, gun-running and other causes of crime, the police seem to have been given carte blanche to employ ‘brute force’ tactics against a few notorious low-life characters regarded as undesirables. From the time of the public killing of Linden ‘Blackie’ London in February 2000 – an event that was carried live on prime-time television – the violent nature of the police special squad became manifest. When details of the Thomas Carroll’s US Embassy visa racket were revealed – establishing that members of the same police special squad were employed as ‘enforcers’ for a corrupt consular officer – they were exposed as being venal as well as violent. No disciplinary or legal action was taken against the culprits.

Left uncorrected, these reckless public security expedients backfired in February 2002 when five desperadoes broke out of the Georgetown Prison. The Troubles which followed were characterised by a wave of criminal violence in which many policemen and innocent citizens were killed. At the height of the crisis, Jagdeo personally promised partial police reforms but they had little effect. Instead of correcting the Force’s deficiencies to enable it to respond to the Troubles, certain elements allowed ‘death squads’ to emerge.

This development precipitated the country’s gravest ministerial crisis since Independence. Gajraj was the subject of a presidential commission of inquiry convened to investigate whether he was “involved in promoting, directing or otherwise engaged in activities which have involved the extra-judicial killing of persons.” The inquiry found, however, that there was no credible evidence against him.

Testimony recently led in a US courtroom makes it clear that Shaheed ‘Roger’ Khan – a self-confessed drug-smuggler – had been allowed by someone acting on behalf of the Guyana Government to acquire intercept equipment and had ordered the killing of certain persons. Who was it?

The administration seemed to learn very early that it could create the impression that it would welcome advice and assistance. Calling for consultancies, convening committees and establishing commissions were easy. As a result, the British Government was invited to conduct several studies aimed at improving law enforcement and the criminal justice system. Little use seems to have been made of their advice especially of recommendations calling for extending oversight, improving governance and enhancing accountability of the security sector.

Jagdeo also convened the Disciplined Forces Commission and the Border and National Security Commission, launched a National Consultation on Crime, and promulgated a National Drug Strategy Master Plan but, as with the British reports, their principal recommendations remained unimplemented. After nearly a decade of engagement, and despite a dangerous security situation, the Guyana Government managed to stall the UK-financed Security Sector Reform Action Plan by raising objections to its conditions.

The Troubles also marked the first shock to the Jagdeo coalition. The decision to present what was in fact a drug war waged by a drug lord as a public safety war and a political conflict demoralized professional policemen and outraged the populace at large.

A discernible crisis strategy − including official intervention to derail coroners’ inquests; obstruction of legal action against culpable police officers and the frustration of bipartisan political approaches aimed at dealing with the causes of crime − became evident. The denial or redress partly explains why retaliatory homicidal attacks were directed at policemen in record numbers. In such a scenario, Jagdeo’s counter-crime plans were a waste of time. By default, criminal elements on all sides were allowed to fill the void created by the absence of good governmental administration and effective law enforcement. Without proper investigation, inquiries and inquests, decision-makers could not comprehend the causes of crimes, much less how to solve the problem.

Governance

Jagdeo’s greatest and most visible achievements over the past decade have been in the economy and social services. He has been tireless in ensuring eligibility for debt relief from the creditor-nations under various Heavily-Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiatives. Economic growth, however, once healthy under Presidents Desmond Hoyte and Cheddi Jagan, slowed after 1997. Foreign investments shrank; unemployment grew; and migration of skilled persons – doctors, nurses and teachers – increased, bleeding the already anaemic public service. Reliance on Chinese and Cuban doctors and British volunteer teachers seems to have become normal administrative practice.

There has also been measurable improvement in rehabilitating primary and secondary schools under foreign-funded schemes such as the Primary Education Improvement Project, Secondary School Reform Project, Guyana Education Access Project and the Basic Education Access and Management Support. Progress in heath, pure water supply, rural electrification and the modernization of infrastructure, especially in transportation – the airport, coastal bridges and roads has been remarkable. Structures such as the National Stadium, National Conference Centre and Berbice River bridge have altered the landscape.

The country’s most serious, recurrent natural disasters – floods – the worst case scenario being the catastrophic great floods of 2005 and 2006, point to Jagdeo’s misplaced priorities and policy choices. There has been a tragic misreading of the effects of global warming and a chronic neglect of sea defences. Much more will have to be done to ensure the integrity of the structures of the huge conservancies – Tapakuma, Boeraserie, East Demerara and Canje – before another costly disaster occurs.

Jagdeo entered office in the aftermath of the Guyana Public Service Union’s 56-day strike of 1999, the most massive for decades. His realistic acceptance of the recommendations of the arbitral tribunal was welcome. When the most important institutions of the state are considered, however, Jagdeo’s performance has been uninspiring. The most grave shortcoming has been the state of the National Assembly, the Judiciary, the Public Service and the Security Forces.

The Needs Assessment conducted by Commonwealth Parliamentary Staff Advisor Sir Michael Davies found that although the legislature was recognised as the paramount institution in the Constitution, it was not being allowed to play its proper role in governance. Reforms are afoot, but they are proceeding slowly. The all-important Judiciary is still affected by the failure to confirm the appointments of the Chancellor and Chief Justice.

The Public Service and the security services are meant to be run by top-level, highly-qualified, professional, career personnel to enable them to counsel political ministers who come and go and train inexperienced subordinates who enter the services. Such performance cannot be achieved by political appointees who feel insecure in their posts and are threatened with the termination of their contracts. Allegations of torture and extra-judicial killings by soldiers and policemen have been brushed aside while the recommendations of the Disciplined Forces Commission Report are still to be implemented. The National Drug Strategy Master Plan which should have aimed at suppressing narco-trafficking has been ignored.

Jagdeo has been careful to make himself his own Minister of Information and, even though there is no ministry, he wields the power of a super-minister. His annual Babu John orations explain much about his philosophy of life and his concept of national unity. Politicising the state-owned news media; maintaining a state monopoly on radio broadcasting; manipulating the allocation of state advertisements; banning a journalist from attending press conferences at the Office of the President; shutting down a television station for four months cannot be indicators of a healthy democracy.

In spite of a respectable economic and social record, Jagdeo’s period of government antagonised the educated classes. His policies debased important institutions, legitimised greed and stifled the public service ethos. The visible material structures that have been erected will last a long time. But so will the invisible legacy of the destruction of hope.

When it was felt that Forbes Burnham and Desmond Hoyte did not perform for the common good, the people turned to Cheddi Jagan. When Janet Jagan assumed office, it was hoped that she would continue her husband’s work. Jagdeo has succeeded in giving the impression that there is nobody to whom to turn. With the People’s National Congress opposition under weak leadership, all serious internal dissent inside the People’s Progressive Party silenced and the state media quite docile, the country is faced with a choice of bad and worse.

Jagdeo, a gifted but bristly politician perfectly suited to the media age, will be remembered for a decade in which enough was not done to suppress soaring narco-trafficking, money-laundering, fuel smuggling and gunrunning trades. The Jagdeo era will also be remembered also for unraveling the few threads of national unity that remained at the end of the last century.