Gary Vyse is an English sports journalist who has followed Howard Eastman’s career with interest from its early days.

By Gary Vyse

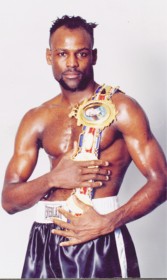

Howard Eastman is a man who can tell you how the boxing light flickers from one moment to the next.

A journey up from sweaty small halls and then bigger arenas in Britain to the flashbulbs of Vegas, he now finds himself punching for pay in his country of birth against Trinidadian Kevin Placide, who holds a modest 11-4-1 record.

Eastman is undoubtedly slipping further and further away from the bright lights.

No longer a world class operator, this proud pugilist refuses to be blown away for good. Not yet anyhow. Refusing to slink off into the sunset, he clings on to the raft of a sport in which he was blessed with exceptional talent before the sands of time and ring wear and tear began to take their toll. But it hasn’t always been this way.

In Britain, Eastman is viewed as a nearly great boxer in a country of nearly great boxers such as Henry Cooper and Herol Graham.

He arrived in London as a youth but after being put out of his home by his father was forced to sleep rough and catch tube trains for warmth. He cultivated a fighting instinct.

With his bright blonde facial hair and a London flat filled with parrots, he was eccentric. But wickedly talented too. When he switched it on and cranked up the pressure he could be devastating.

He scooped British, Commonwealth and European honours – an exceptional feat many boxers could only dream of achieving.

Along the way he broke down world contender Robert McCracken, then 33-1 (who oddly enough went on to become his trainer), smashed up former world champion Hacine Cherifi and outscored Australian world title challenger Sam Soliman.

But Howard is a fighter who has always operated to the beat of his own drum. Someone who will flick the switch and ignite his dazzling combinations only when the mood suits him.

In 2001, his hands were dangling perilously close to world honours but he blew his WBA shot against William Joppy in Las Vegas by coasting and despite having his opponent down in the last round dropped a majority decision.

Eastman retreated back into the shadows and spent the best part of a year away from the game, back in his homeland Guyana.

He eventually came back to Britain, grafted and pulled his way back to world title contention like a moth to a light, only to be disappointed.

Middleweight king Bernard Hopkins fiddled, manoeuvred and peppered his way to a clear and concise victory.

Two more title eliminator shots were thrown Eastman’s way but both eluded his grasp after he was outpointed against Arthur Abraham and stopped on his feet by Edison Miranda.

Eastman had lost his lustre. He resurfaced in Britain but was no longer the fearsome proposition he had once been, losing to average fighters Wayne Elcock and John Duddy.

Which brings us to the here and now in Guyana. Howard will prepare to lace up at Georgetown’s Cliff Anderson Sport Hall against an inferior foe on Saturday, September 26.

Frankly, the smaller 35-year-old Kevin Placide shouldn’t be anywhere near Eastman’s level. In his biggest fight to date he was blown out in four rounds by decent but erratic Englishman Young Mutley last year.

However, time is the great equaliser and while Eastman may be older and wiser, his reflexes and movement are probably not as sharp as they used to be. The granite chin has become more exposed. What’s he hanging on for?

But this 38-year-old stubborn pro is his own man. His boat may be slowly drifting out and the lights may be steadily dimming but Howard – and only Howard – will decide when the time is right to reach for the switch, turn the light off and close the door on his career.

For now Eastman, the man who traded blows with the king, is content to share ring space with smaller, lesser fighters as his career winds down.