By Isabelle de Caires

My earliest memories of my father are of him reading in his beloved Berbice chair in his study. He was there in the morning when we got up and at night when we went to bed.

There was also the daily drone of bets being placed on various unsuspecting horses: words like ‘each-way’ and ‘Kemp-ton’ were as familiar to us as ‘Noddy’ and ‘Anansi’ were to others. Dad was a creature of habit.

His days invariably had a rhythm, a routine. He needed very little sleep in his prime and would regularly read until 2 am, retire to bed and rise at six to read again before going to work. After my parents started the newspaper, and his workload doubled, he absorbed more and more work into this extended day.

Dad’s study was the focal point of our home. It was where we would gather to chat, debate, gossip and pontificate. Even as children, we were encouraged to explain our views, to question what we read, to interrogate assumptions, to listen to and show respect for other opinions. Nothing was sacred.

No one was beyond the pale. Equally, everyone (the youngest, the most hesitant, the least articulate) deserved a hearing. It may sound contrived in retrospect. At the time, it was as natural as breathing. It is only now, in adulthood, and as a parent myself, that I fully appreciate the effort and patience that underpinned this approach.

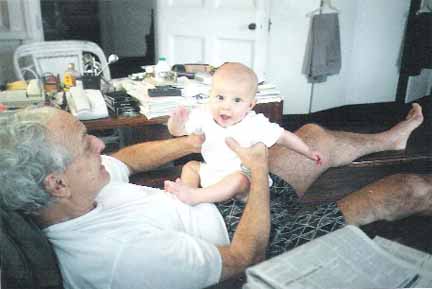

Dad had the same Berbice chair for the four decades of my life. Whenever it threatened to fall apart, someone was summoned to patch it up. It was only with the greatest difficulty (and threats of divorce) that my mother persuaded Dad to change the little cushion that had supported his head for twenty years or so.

When we were very young, my brother and I would sit on either side of my father, for the telling of ‘old-time stories.’ These invariably portrayed him as a bit of a wally, gorging on green mangoes in a competition with friends, running dead last in a race because he was fatter than his friends. He was happy to be the butt of his own jokes and to laugh at himself. A generation later, at my home in London, he reduced us to tears of laughter when he tried to feed my infant daughter a pot of yoghurt and ended up wearing most of it himself. There was an awful lot of laughter, at him and with him, over the years.

My father embodied a stability of thought, of purpose and of principle that were largely at odds with the world around him. Yet he was a complex man, full of contradictions. There was a strength and a stillness at his core: there was also a restlessness, he was never satisfied with what he had achieved, always felt that he could do more. He was a frugal man who lived largely in one room of a big house, his family home. He enjoyed good company, loved to tell a story, but was essentially a shy, private person. He had an enquiring mind, a wide-ranging intellect yet did not enjoy travelling. He spent his life enmeshed in routine yet daily courted the caprice, the unpredictability of gambling. He did not see himself as a particularly brave man and hated violence but was never afraid to stand alone. He usually held opinions that were at odds with many of his peers and yet continued the friendships of his childhood until his death. In this newspaper, he found his great purpose in life. In my mother, the pragmatist who gave flesh and form to his ideals, and in those who continue his work, he found able partners to fulfil it.

Dad grew up in Moray House and returned to live in it with his young family. He spent much of his life reading in the same chair in the same room and would, in his words, have been an odds-on favourite to die there. Fate ruled otherwise. One year after his death, my father’s study is as he left it. The slightly precarious pile of books that sits to the right of the Berbice chair is still there. In death, as in life, my father is slightly at odds with convention: his ashes lie in a box on the table to the left of the Berbice chair. It seems premature to scatter them. He is in repose, very close to the spot where he was happiest.