What’s the difference between juice and drink? How much does one cup of raw rice yield when cooked? Do you know the difference between evaporated milk and pasteurized whole milk? Each week, I get emails with a variety of questions that many of us take for granted that we know; often these questions are food for thought (pardon the obvious phrase). This week, I’ve selected some of the most frequently asked questions to be answered in this edition of the column, with the aim of making us more knowledgeable about food and the choices we make.

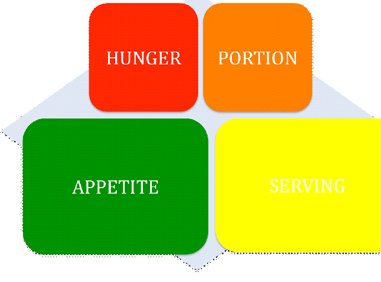

Let’s start by looking at hunger. What is it? Hunger is the need to satisfy a physiological drive. This drive is recognized by signals in our bodies that stimulate us to acquire and consume food. For some people this need results in the abdomen making sounds! I’m sure you’ve heard of people’s tummies growling, or your own when you’re hungry!

Let’s start by looking at hunger. What is it? Hunger is the need to satisfy a physiological drive. This drive is recognized by signals in our bodies that stimulate us to acquire and consume food. For some people this need results in the abdomen making sounds! I’m sure you’ve heard of people’s tummies growling, or your own when you’re hungry!

Appetite is closely linked with hunger. What we eat, when we eat and how much we eat are all factors that affect our appetite. Unlike hunger, which is a physical response to feed the starved body, appetite is based purely on desire. Appetite is the desire to eat specific foods and it should never be confused with hunger; the reason is simple. We can continue to eat (feed our desire) long after our hunger has been satisfied. How many times have you not heard your parents or other people make this remark: “Yuh belly full but yuh eye ain’t full”. In other words, your hunger has been satisfied but because the food is attractive, tasty and available in abundance, you want to eat more; you want to overindulge.

Appetite and hunger bring us to portion size and serving size. Just like hunger and appetite, these two terms are not to be confused because they mean different things. A portion is a measured amount, which equates to a specific caloric value. While a serving is the usual amount that an individual will get at home or when they eat out. Servings vary from one individual to another. They also vary from one home to another and from one eating establishment to another.

Let me explain further. One cup of cooked rice would give you about 180 calories – this is a portion. The measured amount is 1 cup cooked rice; the specific caloric value is 180 calories. Now, how many cups of rice you decide to serve an individual is what would constitute a serving. Therefore, when taking out food for your family you may serve your son 3 cups of rice, your daughter 2 cups of rice, your husband 4 cups of rice and you may serve your self 1½ cups of rice. Do you see how in your own home, the servings vary? But let’s say you serve everyone in your home the same amount of rice, that may not be so when you go to visit your family and friends; their servings might be larger or smaller. That is why the word usual is relative and there is no definite value to it.

Eating establishments also vary their servings though some of the more established restaurants try to maintain a standard based on weight rather than quantity. For example, 5 large shrimp is considered a serving in many restaurants but in a restaurant that’s serving jumbo shrimp, you may only get 3. This difference is based on the assumption that the weight of the 3 jumbo shrimp is equivalent to 5 large shrimp.

I’m sure that you’ve been to restaurants and made one or both of these remarks: “The servings here are too big. I’ll never finish this meal!” or having finished a meal at a different restaurant, “I’m still hungry, they hardly give you any food at all, especially for that price!”

Granted that you know the serving sizes of the rice or pasta or legumes you serve, planning meals for your family and for entertaining would be easy if you also know their yields from the raw to cooked state.

Granted that you know the serving sizes of the rice or pasta or legumes you serve, planning meals for your family and for entertaining would be easy if you also know their yields from the raw to cooked state.

1 cup raw rice yields 3 cups cooked rice

1 cup dried pasta yields 2 cups cooked pasta

1 cup dried legumes yield 2 cups cooked legumes

The reason that these staples bulk up when cooked is because they all absorb water. The dried legumes already take in additional water during the rehydration processes (that’s when we soak the peas overnight in water).

Milk is an everyday ingredient and comes in many varieties (as does everything these days!) There are five varieties that we use regularly, but have you ever stopped to find out what’s the difference? Of course our decision to choose one over the other has to do with taste and personal preference.

Whole milk – milk that contains all of its fat, water and nutrients.

Evaporated milk – all the water has been removed from the whole milk, hence the thicker, creamier taste and texture.

Condensed milk – this is evaporated milk to which loads of sugar has been added. The sugar acts as a preservative.

2% milk – this means that 98% of the fat has been removed from the milk.

Flavoured milk – whole milk to which flavourings such as vanilla, chocolate and strawberry have been added along with sugar.

Talking about varieties, have you noticed that these days, many packaged and canned products come with one or two words stamped on the label? Enriched and fortified.

An enriched product is one that lost some of its nutrients while being processed, and those lost nutrients have been added back either at the level lost or higher. A fortified product is one to which nutrients that are not naturally present have been added. For example, Vitamin D is not naturally found is milk but it is added to the product by some manufacturers. The table salt we use daily does not naturally contain iodine. The mineral is added because it is needed to help in the making of the thyroid hormones that regulate growth and reproduction. A deficiency in iodine can lead to an enlargement of the thyroid gland – goiter. People who like to use lots of gourmet and natural salts need to pay attention to this as the overuse of these types of salts can lead to an iodine deficiency.

And finally, juice versus drink. The differentiation is simple – juice is made with the entire fruit – skin, pulp, seeds (where applicable) and all; it is blended and strained, chilled and served. The sugar in juices is natural; it comes from the fruit itself and is called fructose. This same juice, if sweetened with sugar becomes drink. In other words, as long as sugar has been added, it is now a drink and not a juice. The caloric and nutritional value has changed because of the added sugar. Apart from this main differentiation, many drinks are made only from the extraction of the flavour rather than the use of the entire fruit. For example, sorrel drink is made by steeping the de-seeded fruit in boiling water and leaving it overnight to draw.

Keep the questions coming.