By Tarron Khemraj

Introduction

I agree with Mr. Rajendra Rampersaud’s letter (SN November 30, 2009) that the sugar industry is viable in spite of the many challenges it presently faces. However, I do not believe the industry’s future is secure for the same reasons Rampersaud proposed. Mr. Rampersaud, who is my friend, raised some important points but some peripheral ones.

I intend to focus on the important ones and explain under what circumstances the sugar industry is still viable. Rampersaud’s conjectures are primarily based on idea that liberalization of global sugar markets will increase the market price for sugar. There are several studies that suggest that should Europe and the US remove the protection in their sugar market, world price would increase. Indeed, the Borrell and Pearce (1999) article which Rampersaud cited to buttress his argument notes that world prices could rise by 38% with trade liberalization. The latter, however, is far from convincing. Moreover, we have seen that liberalization under the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) has wiped out substantial price protection for Guyana’s sugar (and other small economies in the Caribbean and Africa). In addition, further liberalization in the US sugar market is unlikely to be realized soon. There are too many political variables to unwind and Guyana just cannot sit and wait when other alternative products that GuySuCo could produce exist.

I intend to focus on the important ones and explain under what circumstances the sugar industry is still viable. Rampersaud’s conjectures are primarily based on idea that liberalization of global sugar markets will increase the market price for sugar. There are several studies that suggest that should Europe and the US remove the protection in their sugar market, world price would increase. Indeed, the Borrell and Pearce (1999) article which Rampersaud cited to buttress his argument notes that world prices could rise by 38% with trade liberalization. The latter, however, is far from convincing. Moreover, we have seen that liberalization under the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) has wiped out substantial price protection for Guyana’s sugar (and other small economies in the Caribbean and Africa). In addition, further liberalization in the US sugar market is unlikely to be realized soon. There are too many political variables to unwind and Guyana just cannot sit and wait when other alternative products that GuySuCo could produce exist.

At the core of Rampersaud’s analysis is a misunderstanding of the elasticity argument I made in my Development Watch column of November 25, 2009. I noted that energy-based products fetch a higher income elasticity than sugar; I would demonstrate this below. According to Borrell and Pearce (1999) sugar consumption in developing economies increased from 66% in 1980 to 76% in 1998. The latter does not negate the income elasticity argument nor is it a very convincing rebuttal.

The best point raised by Rampersaud is the potential to expand sugar exports to the CARICOM market. I agree. However, this does not mean that GuySuCo should not diversify its production base – my concept of viability. It would be better to produce a portfolio of commodities rather than only sugar. This portfolio can be expanded to ethanol and even further into co-generation for East and West Demerara.

Some background data

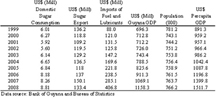

The table below shows some recent trends in Guyana sugar exports, domestic sugar consumption, imports of fuel and lubricants, and the level of GDP (all series are in millions of US$). It is obvious there is low domestic absorption of sugar in Guyana given the limited development of local manufacturing linkages with the sugar industry. We can use the data to calculate a simple long-term income elasticity of sugar (domestic consumption) versus energy income elasticity (import of fuel and lubricants).

Energy income elasticity = % change in imports of fuel and lubricants ÷ % change in per capita GDP (from 1999 to 2008)

Energy income elasticity = (406.8 – 88)/88 ÷ (1511.7 – 891.3)/891.3 = 5.2

Sugar income elasticity = % change in domestic consumption of sugar ÷ % change in per capita GDP (from 1999 to 2008)

Sugar income elasticity = (8.81 – 6.01)/6.01 ÷ (1511.7 – 891.3)/891.3 = 0.67

Therefore, using High School level mathematics and the data from the table below, we obtain an energy income elasticity of 5.2 and a sugar income elasticity of 0.67. It therefore means as Guyana’s average income (per capita GDP) rises by US$1 there is at least US$5 increase in the demand for energy. Meanwhile, the same one unit increase in average income results in less than US$1 rise in domestic consumption of sugar. The implication of these long-term elasticity measures would be explained below; but for now suffice to say that a 1% growth of Guyanese income engenders a stronger demand for energy relative to sugar.

Other studies

A few weeks ago the editor of an economics journal in the UK (International Review of Applied Economics) asked me to referee a paper in which the author (s) used good econometric methods to calculate import elasticities (and other elasticities of interest) for 66 items which the US imports. The same was done for 66 American export items but I would only focus on the import side for obvious reasons. I thought it was a very good study as not only did it reflect sound econometric applications, but also made important micro-level empirical contributions to the literature of import demand functions (and other contributions). I am not aware who the author (s) is/are since it was a blind peer-review process. I hope the other anonymous referee recommends that the paper gets published.

Nevertheless, I would like to share some of the income elasticity measures as they could be of interest to Guyana and moreover they are germane to this column and the argument I have been making. Here are some elasticity estimates that I believe are relevant to Guyana. Aluminium = -0.36, basketware, etc = 0.98, clothing = -0.65, wood & lumber = -1.23, fish and preparations = -0.48, furniture and bedding = 0.86, gem diamonds = 0.58, gold = -0.44, liquefied propane and butane = 1.15, natural gas = 2.17, paper and paper board = -0.77, petroleum = 1.86, rice = -0.08, vegetables and fruits = 0. 67. As we can see my thesis that energy goods have higher income elasticities holds. Some important commodities which Guyana presently produces are inferior goods (meaning the income elasticity is negative) given the estimates of this study. Notice, however, some potentially new industries Guyana could target are normal goods with positive income elasticity estimate; example, furniture making, fruits and vegetables, and of course renewable energy products to substitute for imported fossil fuels. Typically it is difficult to get these measures; hence the usefulness of this study.

Reasons sugar could be viable

What do I mean by the viability of sugar? Viability, in my opinion, means GuySuCo would have the largest positive impact on economic development, job creation growth of per capita GDP, and increase in the living standard of sugar workers. I want to make it clear that the current GuySuCo blueprint overwhelmingly focuses on very short-term measures to restore an accounting profit at the state corporation. These include selling land, squeezing wages (which is natural for a low value commodity like sugar) and packaging of sugar.

Indeed, the GuySuCo blueprint proposes establishing an ethanol plan in 2012. This makes sense. However, why only one ethanol plant? Also, is it not possible to expand co-generation to Demerara and West Berbice? These are the long-term diversification of output that would lead to a larger impact on development and increase wages of sugar workers. However, I am not very optimistic about the ethanol policy as the PPP government does not seem too committed to the idea (I believe it is ideological; remember Fidel Castro had complained against corn ethanol; however we are talking about sugar cane ethanol).

As we found out recently large amounts of GuySuCo lands would be sold off. Furthermore, the Guyanese public, GAWU and sugar workers are not given any transparent indicator who would buy the land and under what arrangements. But even more importantly, into what alternative economic enterprises or production activities the lands that are sold off would be put to use. Selling of GuySuco land makes no sense to me from a long-term economic perspective (even though it would buttress short-term cash flow and accounting profit). I hope GAWU and the Guyanese electorate are taking note – especially taking note of who will get the land.

Furthermore, GuySuCo’s ambivalent ethanol policy is not well conceived. It cannot work unless the government makes a clear commitment to establish an initial national E10 policy (and subsequently increase the mix of ethanol as new feedstock come on stream or even make commitment to shift to flex fuel vehicles). I am aware that recently the AFC made a commitment to set in place a national ethanol policy should it win the 2011 election. Of course, that is the right thing to do since it is well known that creating new products and processes are important for welfare advancements and development (and of course for sugar workers to really start earning better wages). Brazil started making clear national commitments in 1975.

The elasticity measures above clearly demonstrate that renewable energy industrial policies will have a larger effect on the demand for energy from the higher incomes created from now products. The higher incomes, in turn, would feedback to higher levels of demand for product that could be made right here in Guyana. Therefore, Guyana cannot go wrong by actively pursuing renewable energy industrial policies. Renewable energy is also good for the environment and also creates new wealth and jobs.

A national E10 policy could also be backed up by a B10 policy (that is a mix of 10% bio-diesel into imported diesel). This would open the way for new coconut plantations, the planting of coconut trees on marginal lands (and even along river beds), and the activation of demand for existing coconut farmers. In addition to bio-diesel, coconuts have many other agro-industrial applications like bottling of water and co-generation of electricity from coconut waste/husk/shell to complement the sugar bagasse co-generation network. Coconut trees also absorb carbon from the atmosphere and therefore, in principle, could allow coconut farmers to claim carbon credits as these markets develop in the post-Copenhagen agreement.

Finally, the national renewable energy policy would save foreign exchange (as the import of oil and diesel is diminished) and promote energy independence. It also opens up new industries and processes for GuySuCo – the thing that really matters for development. Thus it is possible to save the environment, engender wealth and jobs, and obtain energy security simultaneously. This is the real meaning of viability (a social viability) and not mere short-term quick fixes.

Next column: a proposal for a State Development Bank.

Please send comments and critiques to tkhemraj@ncf.edu