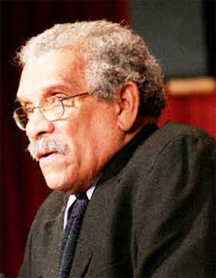

Derek Walcott, the Carib-bean’s foremost poet and playwright, who was born in Castries, St Lucia on January 23, 1930, turns 80 this weekend. The distinguished writer, who is also a painter as well as critic of the arts and literature, won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1992. In Trinidad, where he lived for 17 years between 1959 and 1977, a lavish birthday celebration put up by the UWI, St Augustine Campus was completed only yesterday, built around an academic conference titled Interlocking Basins of the Globe.

Among the many topics being discussed was Walcott’s artistic and intellectual engagement with Haiti, which dates back to 1949 when he was writing his earliest plays. That engagement continued through other plays and a film. It was therefore one of the key discussion points and subjects of analysis during the celebrations.

Among the many topics being discussed was Walcott’s artistic and intellectual engagement with Haiti, which dates back to 1949 when he was writing his earliest plays. That engagement continued through other plays and a film. It was therefore one of the key discussion points and subjects of analysis during the celebrations.

However, these activities had only just begun when the region was shaken by the bad news of the devastating earthquake measuring 7.3 on the Richter scale which wreaked severe damage and caused enormous loss of life in Haiti. This was major and tragic destruction in a nation already troubled by poverty and instability, still not quite recovered from severe flooding. This new calamity struck a discordant note in the middle of what set out to be a commemoration of Walcott’s work on Haiti. It turned celebration into sadness, sympathy and the mobilisation of material assistance for the victims.

Like CLR James did before him, Walcott set out to dramatise the heroic in the history of the Caribbean, highlighting the example of Haiti between 1793 and 1803. At that time a former slave, Toussaint, who was coachman to a planter, led slaves in the Haitian Revolution.

It was a triumph for them in the defeat of the French, of the legendary Napoleon, to create an independent Caribbean state formed after a successful slave revolt. (Some historians argue that the 1763 revolution in Berbice was the first to achieve this.) Both James and Walcott wrote plays, The Black Jacobins, Henri Christophe, Drums and Colours and Haytian Earth to show black slaves in a successful bid for freedom, achieving independence, becoming leaders, diplomats and kings.

However, it was not all triumph and positive development, as the dramatists showed and as is illustrated in the troubled history and state of affairs in contemporary Haiti.

The earthquake is only the most recent event in an unstable nation continuously afflicted by man-made issues and natural disasters since its political break with Europe more than 200 years ago.

The plays suggest how revolutions turn counter to their objectives, how some black

leaders with a hatred for whites end up as despots who enslave blacks. James showed a Dessalines who bitterly despised whites in his outward expressions yet embraced everything European after crowning himself Emperor of Haiti.

Contrary to the ideal expectations in what is still hailed a heroic nation that set an example in the Caribbean, the former colony of Saint Domingue became the poorest country in the hemisphere. The independent nation had to struggle on its own and no sturdy or adequate infrastructure was ever

built. It suffered a series of coup d’états and dictatorships right into contemporary times.

When the country thought it was rid of Papa Doc François Duvalier and his successor Baby Doc, the cycle was really not yet over. Despite its fragile attempts at democracy the nation has been increasingly unstable since the overthrow of the duly elected Jean Bertrand Aristide.

It hardly manages to recover from bouts of destablising violence never helped by destructive hurricanes and floods, and now this earthquake.

James wrote the first play that treats the revolution in 1936 with a celebration of the hero Toussaint and the historic achievements of the slaves of Saint Domingue, but gave a Marxist analysis of the new generals turned kings like Dessalines, and the betrayal of the former slaves. Then Walcott became interested in the subject in 1949. He wrote Henri Christophe, first performed by the St Lucia Arts Guild in 1950. It was the first of his plays in which he searched for Caribbean heroes. Yet his concern for the heroic allowed him to study Christophe as a counter-revolutionary leader in a play still considered as a work which highlighted a historic Caribbean triumph.

This was so in more ways than one. Its next performance was in London at the theatre of Hans Crescent House, Students Residence, London, on January 25-27, 1952. The production of it may be regarded as the first attempt at ‘Carifesta’ before Carifesta. It was a truly regional effort, a foreshadowing of the eventual West Indies Federation in 1958, and probably the first time there was any significant regional artistic collaboration. Henri Christophe was directed by Trinidadian Errol Hill with Jamaican Noel Vaz as Stage Manager and had a cast that, according to Walcott biographer, the critic Bruce King, “included many actors who would become leading West Indian writers, artists, teachers and politicians.” Among them were George Lamming, Errol John, Frank Pilgrim, ANR Robinson and Roy Augier.

Walcott renewed this search for the heroic in Drums and Colours which was performed under even more significant circumstances in 1960. First, it was the second and greater attempt at ‘Carifesta’ before Carifesta. A West Indian Festival of the Arts was planned to take place in Port of Spain between April 25 and May 1, 1960 to celebrate the opening of the Federal Parliament of the newly formed West Indies Federation (1958). In the play there is a carnival in which masqueraders played Caribbean heroes including the four on whom the play focused: Toussaint L’Ouverture, Christopher Columbus, Sir Walter Ralegh and George William Gordon.

Walcott’s third play on this theme came out of similar circumstances. He was invited by the St Lucian government to do a revival of Henri Christophe to celebrate the 150 years after slavery in 1984. Walcott made a proposal to do Haytian Earth instead. This was accepted and the play was first staged then. Its most recent production was in Trinidad in 2005. In this work Walcott articulates more than previously, the betrayal of the Haitian revolution.

He presents the usual genuine hero Tous-saint, but exposes the despotic tyrannies of Dessalines. He shows the peasants, the people of the ‘Haitian earth’ to be the true heroes of the revolution who should inherit its benefits. But instead they are raped by Dessalines and killed off by Christophe who also becomes king after him.

In a search for Caribbean heroes, Walcott both celebrates and laments Haiti. In the recent performances in Trinidad, however, there was controversy as there were those who objected to Walcott’s treatment of the theme.

Yet, what the dramatist presents raises issues about an ironic emancipation of the slaves and a questionable freedom in an independent nation. It pulled off a successful revolt against slavery, drove out the colonisers and the slavers, and established a black nation. Liberation, progress and prosperity were to follow. But for these achievements Haiti is still waiting.