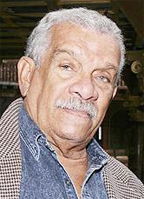

Derek Walcott achieved yet another significant chronological landmark with the celebration of his birthday yesterday, January 23, at the end of the first decade in the twenty-first century. During the week before that, he was honoured as a Nobel Laureate at a conference and other related activities at the UWI St Augustine Campus in Trinidad in a quite elaborate affair. It was the third and final in a three-part series in which the Caribbean’s three Nobel Laureates were glorified. Similar commemorative events were held for decorated fiction writer, novelist, travel writer and analyst, the controversial Vidia Naipaul, and for economist, Arthur Lewis.

Walcott’s work as the leading poet and playwright of the region, regarded as the finest poet of the world today, as a theatre director, a literary critic, a painter and one of the dominant contemporary literary personalities was examined and exhibited between January 12 and 16. The conference on the UWI campus was titled with the theme Interlocking Basins of the Globe. It presented papers and panels, readings and a book signing by Walcott, a library archival exhibition, screenings of films of a few of his works, performances of his drama and an exhibition of his paintings. The theatre exhibited were excerpts from Walcott’s poem The Schooner, Flight and from his theatre in a presentation called Fragments by Arts in Action.

A full performance of the play Pantomime directed by Robert Leyshon in Barbados was brought over by the Open Campus for a brief run in Trinidad to coincide with the conference activities. The cast also fielded questions and spoke with secondary school students since the play is on the syllabus for CAPE Literature.

Included in the conference programme was a special panel made up of members of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop which was founded by Walcott in 1959 and for which he was artistic director until 1977, when they had a bitter falling out and parting of ways. Walcott then started his work at the University of Boston. It was the culmination of domestic as well as professional issues and a break-up with not only the company but with his second wife. The panel evaded the question and made no mention of those matters.

However, while that session was meant to focus on 17 years of work in the theatre by the region’s greatest playwright and the director of a theatre company, there has been a general limited attention paid to Walcott’s drama. Compared to the great volumes on his poetry, critical output on the theatre has been considerably under-represented. Attention to his own criticism, since he has written reviews, critical essays and theoretical discourse, has been even less.

Moreover, Walcott is also an artist; he has been a painter all his life, but serious critical attention to his drawings and paintings has been even more scarce.

The first critic to review Walcott was Harold Simmons, who was a dominant cultural figure in St Lucia roughly between 1944 and 1966. He wrote two notices of importance when Walcott first came to light as a teenage artist of great promise in 1949. In that year Simmons reviewed the first collection of poetry, 25 Poems, and around the same time he wrote on a joint art exhibition by two close friends Garth St Omer and Derek Walcott. At that time it seems, Walcott intended to be a painter as well as a writer, and was taking both disciplines equally seriously. St Omer, however, was the better talent in art and, in fact, went on to be the island’s most accomplished and acknowledged artist while his friend went on to be the equivalent in poetry and drama.

True enough, the literature and theatre very soon overshadowed the painting, and his career took off so emphatically that the art work was easily either forgotten or swept into the background as a minor pastime. There was so little critical attention because of the overwhelming dominance of his major preoccupations and because after he left home for Jamaica in 1950 he was not regarded as anything more than an amateur painter of watercolours. It was something he did merely to amuse himself in between the more serious work.

From time to time, however, there were glimpses of it and it demanded some attention because Walcott continued to produce work, and in his more recent years he himself seems to have given it an upgrade. He has said that he spends more time painting now, and has done so in recent years more than in the few decades previously. There have even been exhibitions of his paintings.

The most recent, of course, was that mounted by UWI, St Augustine January 13 to 15, 2010 as part of the Interlocking Basins of the Globe Conference. This was a small exhibition of work in the collection of the Walcott family put together by his daughters Anna Walcott Hardy and Elizabeth Walcott Hackshaw, both on the staff of UWI St Augustine. There was also one piece which had been donated to the university library by its owner in memory of a former Head of the English Department Patricia Ismond, herself a Walcott scholar. The collection on display reflected an important part of the general pattern of the Nobel Laureate’s art work.

Walcott has worked mostly in watercolour, although he has produced work in oil on canvas as well. But his work in oil is noticeably less accomplished than his watercolours. One piece in oil is of particular note and stands out from the rest. Country Fete, 2001 is a reminder of the artist’s more serious concentration on painting in recent years. It is a large canvas depicting a rural scene, a fairly colourful country dance which demonstrates the artist’s good command of anatomy a bit more than it does of his command of colour. There is a small band of musicians playing the usual ensemble of instruments befitting the type of gaily attired revellers, mostly female, dancing. There is close attention to detail, including the ubiquitous rum bottle and a couple of half-empty glasses within easy reach of the musicians. The mode of flamboyant dress is accurate for the country village as it is for a time in the past many decades ago.

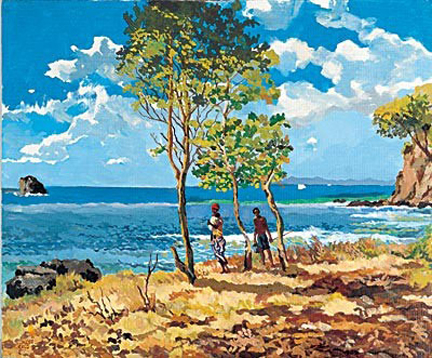

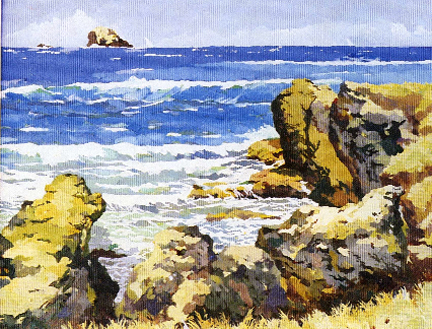

Others in oil, like Horses at Sunrise, 2001, are less spectacular and of little note. They are realistic pieces; as an artist, Walcott is a realist and has not produced abstract work. It is the same in his watercolours which exhibit another important characteristic of his. He is largely a landscape painter and seascapes as well as impressions of places play consistently and for a long time on his eye and memory.

For example, At the Gate, Petit Valley (circa 1980), and Petit Valley (2000) seem to be impressions and memories of Walcott’s former residence in Trinidad close to the scenes he has painted. In the former, the work in watercolour is dominated by detailed representation of large leaves in the foreground carefully and realistically reproduced. Santa Cruz landscape (2001), Santa Cruz Landscape (1999) and La Pastora (1992) are reminiscent of a quartet of recent poems by Walcott which reflect on the landscape of these localities in Trinidad.

The peculiarities of his style are not always consistent. He can draw, and indeed he uses the fine brush very well to delineate shapes, nature and life figures in very realistic fashion. Yet at times he produces impressive landscapes with vegetation using the style and techniques of impressionism. In these works his use of colour is at its best.

Some years ago there was an exhibition of Walcott’s watercolours in Port of Spain and some of these were reproduced as the featured work on one of the impressive series of CLICO calendars. (This series, which ran through the 1990s, was discontinued some time ago.) Many of these depicted scenes and characters from the plays, especially Ti Jean and His Brothers.