Water as a factor in Guianese History

Guyana Review reprints this essay by W.T. Lord that was first published in One People, One Nation One Destiny: Selections from Guianese History and Culture Week, 1958.

By W. T. Lord, ISO

Guiana, the land of many waters, conjures up in the minds of writers and imaginative persons the El Dorado of Raleigh, the war-canoes of the Caribs, the legend of the Massakuruman of the Berbice River and of the Fairmaids of the Essequibo, the Kassekaitya or the River of Death of the Atorais.

But, in this day and age it means much more than that for the impact of civilization on British Guiana brought with it many problems, some of which weren’t foreseen by the early settlers who decided to establish settlements on the lush valleys of the rivers. This appeared to be the logical course – both as a measure of security against enemies from outside and to ensure supplies of drinking water from the fresh inland streams.

These settlements were abandoned later for the more fertile land of the coastal belt, a low-lying, flat and, in some cases swampy strip of silt from the sea. Here, the fact that the rivers were navigable for the sailing craft of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries removed the need for early settlers to build roads through the jungle and this has in turn influenced the trend of development for three centuries.

In all the major rivers, settlements were established at the limits of navigation for vessels − for example, Wismar about 65 miles up the Demerara River, Paradise about 100 miles up the Berbice River, and Bartica about 40 miles up the Essequibo River. In the days of the early Dutch settlers, the original settlements from which the government of the colonies was administered were Fort Nassau, about 56 miles up the Berbice river, Fort Zeelandia, about 14 miles up the Essequibo river and Borselen, an island about 15 miles up the Demerara River. It is significant that the names of the three counties which form British Guiana today have been taken from the three rivers on which the former administrative centres had been established.

Unfortunately, whenever the colonies decided to establish settlements they were faced with water problems. The lower reaches of the river are fertile but are subject to inundation during seasons of heavy rainfall. This condition had to be overcome by building dykes or river dams which protected the land from the inroads of the river. But another problem arose.

The river dams, apart from providing protection from the river, impounded water as well. This water was discharged into drainage canals running inland at right angles to the river and was controlled by sluice gates. These sluice gates or kokers are opened on a falling tide and shut when the tide rises to the height of the outfall water. So, in many cases during heavy weather, pumps have to be used to discharge the flood waters. This system of surrounding an area of land by dams which are intersected by canals is called an empolder.

The settlers had found that the coastal plain was more fertile and offered greater possibilities for agriculture. The greater part of the coastline is, however, slightly below the level of ordinary spring tides, which flood the unprotected parts. The margin is protected to some extent by natural growth of mangrove and courida behind which there are in some places flat, grassy savannah land, mostly inundated during the rainy season.

There were two major problems for it is on this coastal plain that the economy of the country mainly depends. On the one hand, the continuous struggle against inroads from the sea and, on the other, against perennial floods brought about by the rivers during periods of heavy rainfall. This calls for the utmost skill of hydraulic engineers.

Work was first started by the Dutch who build dykes or dams along the seashore, reinforced with bundles of brushwood. Later, after the colonies of Berbice, Demerara and Essequibo had been amalgamated under British rule, the encroachment of the sea and tidal river water on the capital, Georgetown, had reached such serious proportions that it was necessary to construct more permanent defences.

You may remember that a concrete sea wall was started about the year 1850 to protect Georgetown from further erosion by the sea. This took some 30 years to build and extended for about a mile and a half up to Kitty Village. This wall was further extended for many miles eastwards along the coast and along the West Coast of Demerara as well. Sea defences may be regarded as a major colonial problem for, without them, cultivation of the coastlands would be at a standstill.

Another result was that the sea dams and river dams also came to be used by the settlers as roads. These have been developed and have formed parts of the main coastal and riverain roads up to the present time and, in many cases, breaches in the sea defences have caused the public roads to be retired further inland.

The economy of British Guiana is dependent chiefly on agriculture and, whilst agriculture cannot be sustained without water, the supply or retention of abundant water is needed at the right stage for the successful cultivation of the second most important agriculture product of the country. Liberal supplies of fresh water are needed in the early stages of rice cultivation in order to ensure a rich harvest.

This raises the important question of irrigation by which sugar and rice lands are supplied with water. There are no lakes large enough to be used as conservancies and these have had to be constructed from swamplands fed by the coastal streams. From these the supply of water needed for the sugar and rice lands and the towns and villages on the coast is regulated. Millions of dollars have been, and are being spent to provide adequate irrigation and drainage for the coastlands. May I just add that the “Hutchinson plans” are to harness the rivers for this purpose.

These conservancies or artificial lakes and the marshy lands around them also serve in some degree to help raise the water table of the land, which is of great benefit to the farmers, who in certain areas are forced to convey water by drains and ditches considerable distances to irrigate their crops or water their livestock. The benefit of irrigation schemes will be more effective when efforts are directed to control floods at their source rather than by expensive and sometimes inadequate dams and other means at the lower reaches of the rivers.

Adoption of a proper plan for flood control would also result in improved navigation, the creation of permanent pools or lakes and, of course, in preventing losses to farmers and property holders located within the area and would prove of inestimable value to the community.

Were it not for the proximity of the navigable rivers to most of the forests of merchantable timber, the timber industry would be at a standstill. Whilst a great deal of haulage by which tractor and trailer is carried out in the forest, the major transportation of local timber and firewood is by water. Today, huge pontoons of a capacity undreamt of even 15 years ago are now towed from the timber concessions along the rivers to the main sawmills of the Colony and to ocean-going vessels for markets overseas.

Exploration of the water courses and rivers of the Colony gave rise to another industry and added a new facet to the economy of the country. As long ago as 1702, the travels and investigations of a few intrepid pioneers and geologists disclosed the occurrence of gold, but it was not until the latter part of the 19th century that gold and diamonds were discovered in the Colony in paying quantities, and no yields are obtainable prior to 1884.

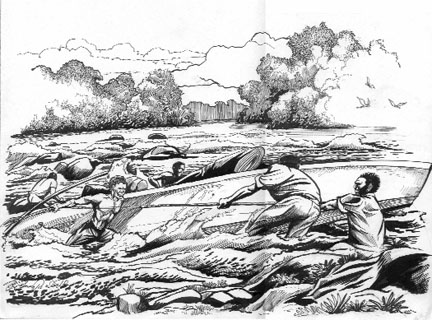

The major part of the gold and all of the diamonds have been obtained from alluvial washing in the beds of rivers and creeks by hand methods from hundreds of small workings scattered throughout the Mazaruni, Cuyuni, Potaro, Essequibo and North West Districts. This has provided a means of livelihood for thousands of men who pursue that elusive lady – Fortune – in the gold and diamond fields year in and year out. Today, dredging of the rivers produces over 75 per cent of the output of gold in the Colony and water plays a most important part in working the alluvial deposits.

No narrative on the effect of water on the history of British Guiana would be complete without reference to one of the most important physical features of the Colony – this of course is the famous Kaieteur Falls – where hundreds of thousands of tons of water, capable of being harnessed into hundreds of thousands of horse-power to drive the wheels of industry, are running to waste. Probably no colonial territory in the Commonwealth possesses hydro-electric resources such as may be found in British Guiana.

The Potaro, Cuyuni, Demerara and Essequibo are all potential sources of energy whence all the power needed for rural electrification, the bauxite and sugar industries and other public utilities and industries might be supplied. Investigations into the hydro-electric potential of these rivers are now being carried out, the satisfactory outcome of which might well change the economy of the country. For, in the words of two engineers who visited the Colony some years ago, “If cheap electric power can be provided there should be no reason why British Guiana should not become the industrial centre of the Caribbean.

It is fitting to close these remarks on water in British Guiana with extracts from an article on Kaieteur Falls which appeared in Blackwood’s Magazine of November, 1917 – when the author of that article looked through a cloud of mist on the Kaieteur plateau:

“Slowly the clouds rolled away, and like a curtain withdrawn, revealed the most awful scene I have ever witnessed. Here was a mighty river, pouring with a force that suggested terrible wrath, over a precipice over eight hundred feet high, down into what seemed unfathomable depths. A sense of unreasoning dread sought to force me from the eerie rock on which I stood. But so great was the fascination of a power so vast that it is as inexorable as fate, so great was its hidden influence, that it drew me forward. I gazed at the tossing waters and into the maelstrom below with eyes that I could not turn away, and yet with a sense of puny helplessness, an oppressive consciousness that I was standing in the presence of a power before which the boasted might of man is nought. In the jungle it is the water that really dominates, not the sun as in desert lands. The forest owes its life to the never-ceasing rains, and all the jungle animals are water lovers. The rivers are the highways, the only means by which man may go from place to place. Therefore I could not help feeling that I had found in Kaieteur an expression of the great secret mystery of the jungle.”