Introduction

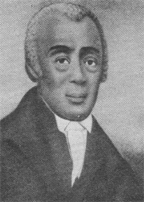

Frustrated by the biased representation or no representation of blacks in American history books, the Harvard Scholar, Dr. Carter Woodson was determined “to bring black history into the public arena”. To this end, in 1926 during the second week of February, he organized the first annual Negro History Week “to make the world see the Negro as a participant rather than as a lay history” Over time it evolved into Black History Month which we in the Caribbean with a large American Diaspora have also embraced. In a similar fashion, frustrated by the discriminatory actions of the leaders of the St Georges United Methodist Church which tried to relegate them to second class Christians, the Rev. Richard Allen and Rev. Absalom Jones led the black members out of the church. Allen subsequently founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church which today has districts in the Caribbean, Europe and Africa. One of Allen’s many biographers, Guyanese born, Rev. Frederick Hilborn Talbot, himself an AME bishop, described him as “God’s Fearless Prophet” for “his prophetic pronouncements expressed in the sermons he preached and in the hymnody that he developed, as well, as in the congregations he established, in the denomination that he founded, and in the missions that he spearheaded.” In the next two articles, I will examine the life and work of this great African American whose 250th birth anniversary will be celebrated worldwide by AME ‘s this Sunday, February 14, 2010.

His early life and conversion

Nearly a decade and a half before Britain’s thirteen American colonies fought their war of independence and became the United States of America, Richard Allen was born a slave on St. Valentine’s day 1760. His parents and their four children were domestic slaves of a Quaker lawyer and Jurist, Benjamin Chew. However, financial problems forced Chew to sell Allen’s parents and their four children, most fortunately, as a family to a plantation owner, Stokeley Sturgis. Allen‘s family moved from the relative comfort of being domestic slaves to the more back breaking toil of field slaves. Not long after, Sturgis himself encountered financial problems and the Allen’s family faced one of the most cruel, hurtful an distinctive aspect of chattel slavery – the separation of his family.

His mother and two of his siblings were sold to Sturgis’s creditors but Allen and his brother remained on Sturgis’ plantation.

Allen and his brother were allowed to attend meetings of the local Methodist society and he was converted at age 17 by an itinerant Methodist preacher, Freeborn Garretson. For several years Allen studied the Catechism and in the process learned to “read, write and articulate,” Allen began evangelizing and attended church services so regularly that he began to be criticized by local slave owners. To counteract this, Allen and his brother worked more zealously for their master, completing their allotted tasks promptly and well. Their attitude gave the lie to the long held belief of slave masters in the Americas that “slaves who had religion” were unreliable and lazy. So impressed was his owner that religion made slaves better and not worse, he allowed Allen to invite Methodist preachers to come to his plantation to hold religious services. On one such visit by Rev. Freeborn Garretson, Sturgis was converted. He was particularly moved by the statement that on Judgment Day, slave owners would be weighed and found wanting. However, this was not enough for him to free his slaves but he allowed them to purchase their freedom. Richard Allen and his brother were valued at 2,000 continental dollars, and in 1777 Allen completed the purchase.

Ministry and “Exodus”

Allen was licensed to preach in 1782 and, according to Talbot, Allen in his autobiography discussed his many itineraries to the states of Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylva-nia and Maryland. They were made possible by the fact that after the revolutionary war in 1783, lay preachers of the Wesleyan movement were free to travel and Allen claimed that he then traveled extensively to preach the gospel. In those early years, Allen did much of his preaching to mostly white audiences but he reached his Black brothers through odd jobbing on white plantations. Allen recalled the specific acts of kindness and hospitality extended to him by many people mostly white whom he met. In 1784/1785 Richard Allen was one of only two black Americans who attended the Christmas Conference that created the Methodist church in America.

In 1783 after his travels Allen had returned to Philadelphia. He was qualified to preach in1784 and joined the mainly white congregation of St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church. His efforts preaching to blacks and whites from New York to South Carolina attracted the attention of Methodist leaders including the first American Bishop of the Methodist Church, Francis Asbury. In 1786, he was allowed to hold services but in the morning at 5.30 a. m. His spirited preaching led to increased attendance by black people at St. Georges. Even though this caused alarm among the white congregants, the white elders of the church rejected Allen’s request for a separate place of worship for the black congregants. One Sunday morning, the sexton asked the black congregants to vacate the seats they had formerly occupied and stand around the Sanctuary. Then on a Sunday, November 1787, they were met by the Sexton at the door and instructed to go to the gallery which they had helped to construct and see where to sit. This they did and proceeded to occupy the seats over the ones they had occupied below. However, this did not sit well with the white congregants below. According to Allen:

Meeting had begun, and they were nearly done singing, and just as we got to the seats, the elder said, ’Let us pray’ We had not been long upon our knees before I heard considerable scuffling and low talking. I raised my head up and saw one of the trustees having hold of the Rev. Absalom Jones, pulling him off his knees and saying, ‘You must get up, you must not kneel here.’ The Rev. Absalom Jones replied, ’Wait until prayer is over…’[the trustee] said, No, you must get up now, or I will call aid and force you away.’ Mr. Jones said, ‘Wait until prayer is over, and I will get up and trouble you no more .’With that he beckoned one of the other trustees to come to his assistance. He came, and went to William White to pull him up.

By this time prayer was over, and we all went out of the church in a body, and they were no more plagued with us in the church.

Talbot stated that the dramatic “exodus” caused by thoughtless and deliberate acts of humiliation created quite a stir in the “City of ‘Brotherly Love.’” It marked the “Genesis” of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.” He continued that this incident, like a pebble in a pond, set in motion wide ripples of protest. To illustrate, he cited the author Lerone Bennett, Jr. who described the impact of the incident thus:

White people were no more plagued by Negroes in thousands of churches. For the Philadelphia incident – the first nonviolent public demonstration by free Negroes- was a focal point in national protest movement.

Without concert, without conscious planning, Negroes in the cities in the North and South walked out of white churches, and established their own institutions.

All of this was taking place among free blacks in the USA in1787 little more than a decade after the 13 colonies had gained their independence from Britain and the “Peculiar Institution” and the slavocracy who ran it were the dominant influence in the South. 1787 was also the year when Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson and others formed a committee to set to work “to procure and publish such information as may tend to the abolition of the slave trade.” This created the impetus first for the abolition of the slave trade in 1807 and the emancipation of the slaves in the British West Indies in 1833.

Earlier the same year, April 1787, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones had established the Free African Society (FAS). Its aim was, in addition to worship, to help peoples of African descent “to become self reliant, independent and thrifty.” It censored drunkenness and condemned promiscuity. This mutual aid, benevolent organization also assisted fugitive slaves and new migrants to the city. However in 1789, when the FAS adopted several extreme Quaker practices, Allen, the staunch Methodist, led a withdrawal of those who preferred more orthodox Methodist practices. In 1794, Allen refused the position of pastor of the church the FAS had built, St Thomas African Episcopal (formerly Anglican) Church. The position was eventually accepted by Absalom Jones. Since the 1740’s the majority of the city’s black community had been Anglicans but according to Allen: “I informed them that I could not be anything else but a Methodist, as I was born and awakened under them.”

In the next article, the evolution of “Mother Bethel”, Bishop Allen and his outreach and the AME church in Guyana will be examined.