The President’s failure to assent to several Bills passed by the National Assembly in 2006, which lapsed when the Assembly was prorogued, has been debated on numerous occasions in the press. The Constitution in Article 170 requires the President, if he withholds his assent to a Bill passed by the National Assembly, to refer the legislative measure to the Speaker of the National Assembly within twenty-one days after it was presented to him for his assent, giving reasons for withholding his assent.

The clear intention must have been that if the President did not exercise the power to refer a Bill to the National Assembly, he would expeditiously assent to it within the twenty-one days.

Despite the costly and embarrassing experience of 2006, the situation has been repeated in respect of most of the Bills passed in 2009. Of the thirty nine passed, thirty six were assented but only five were assented to within the constitutional deadline. Principal among these were the Acts 7, 8, 16, 27, 40 (see Appendix A). For the others, the average time taken by the President to assent was 66 days, within the range 28 days to 189 days.

There was another dimension noted in the more recent cases of presidential delay. A number of the Acts were published in predated Gazettes, effectively with retrospective effect, since the law is that an Act comes into operation on the date of publication in the Gazette unless an Order is required.

There now remain three Bills which have been passed but not yet assented: Act No. 28 – Local Government Commission Act 2009 establishing a Commission by that name; Act No. 32 – Private Security Services (Regulation) Act 2009 empowering the Commissioner of Police to regulate and control private security services; and Act No. 38 – Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters Act 2009 providing for mutual assistance in criminal matters between Guyana and Commonwealth countries, and other countries with which Guyana has a treaty. This is an average of 116 days since being passed by the National Assembly.

It is difficult to understand why the Government would wish to add to the Commissioner’s already heavy workload or wish to regulate the relationships between security firms and their clients. That is a matter of freely negotiated contracts and the marketplace. The case of the Local Government Commission is easier to understand, since it leaves, in the hands of a Minister of the Government, the entire political control of local government, due to have elections in another few months.

One senior counsel is of the view that once the President has not notified the National Assembly that he is withholding assent, then by necessary implication, the Bill has to be treated as so assented. If this view is correct, the Bill becomes law without meeting the statutory rule that a Bill becomes law only when it is gazetted.

It is of course unacceptable that the President would continue to act in clear violation with the Constitution. But that does not remove the role or obligation of the parliamentary management committee and the secretariat of the National Assembly to facilitate the process. The Speaker of the National Assembly has argued that parliament’s constitutional role ends when the bills are forwarded to the President for his assent. Given that this matter has been extensively discussed publicly, it may be appropriate for the parliamentary opposition to seek clarification from the courts.

Whoever is right, this is really a messy and amateurish way for two of the most important institutions in the land to conduct the country’s affairs.

Whither Guysuco?

With all the bad news coming out of the state-owned Guyana Sugar Corporation practically for the entire 2009, the news that the sugar sector ultimately caused the economy to report growth for the full year, must have come as a great relief to the Government.

Minister Singh in his presentation gave a litany of woes faced by the Corporation during the year, among which were erratic weather, pest infestation and damage, aged capital equipment, and industrial action. He could have added public disclosure about management salaries; publicity about the Corporation being unable to pay its wage bill on time; and a shortage of skills at all levels of the industry.

The Minister and the Government continue to give the mistaken impression that the issue facing Guysuco is one of production. That is simplistic. For Guysuco, productivity and profitability are survival issues. Volumes may help production, exports and GDP, but not necessarily profitability. Not that production is unimportant: it would surely have been good if the Corporation were able to achieve in 2009 its 1999 production of 321,871 tonnes. That is a long way from the 233,000 tonnes produced in 2009.

This Government has bet its shirt on the industry in which it continues to inject massive sums, in various forms, taken from other sectors of the economy. It is not without significance that the amount that will be injected in Guysuco is about the sum budgeted in 2010 as receipts from Norway. The Government has effectively assumed the debts of the Corporation, while its business operations have been racking losses of billions of dollars annually.

This is after all, not bauxite or GNCB. For a PPP Government it is not whether Guysuco is too big to fail – it is simply too important to fail. Yet even as the Minister announced, ten billion dollars in 2010 capital expenditure by the Corporation, money which the Corporation does not have, he was careful enough to use conditional language in discussing the emergence of an efficient and competitive industry. The bets now are on what an interim Board developed as a Turnaround Plan.

Much thought must have gone into that Turnaround Plan: but some observers believe that the issues facing the industry are still not being confronted. They argue that there is a reluctance to put some of those issues on the table – the professionalisation of the management structure; insulation from political interference; low worker morale; consolidation of the industry and the possible closure of some estates; and the human resource shortage referred to above.

The Minister may have found it convenient to compare the 233,000 tonnes produced in 2009 with the 226,000 tonnes produced in 2008. But that was misleading. A better measure would have been the actual production against budget; profitability; yield; productivity; and similar factors. What if for some reason the Government finds itself unable to under-write the industry, or if the field workers continue to find the company a poor choice of employer?

Fortunately for the Corporation, the international price of sugar has risen to lucrative levels just when the sharp EU price cuts took ultimate effect. That allows some breathing space. But that is still below the price at which some of the estates produce. The future of those estates has to be confronted. Even if the much heralded Skeldon Project eventually operates at full capacity, it would not be able to service its debts and carry the unprofitable estates as well.

These are the realities which the Minister did not confront. The longer the problems are ignored, the more costly and drastic the solutions will eventually be. It is futile to complain about adverse weather and lost man-days – these will always be with you.

Conclusion

Once again it is a disappointing Budget. Again, it is more about what the Minister did not say, than what he said. The traditional sectors and the public sector continue to dominate, while the economy now subsidises sugar, water and electricity. In the twentieth year of the Economic Recovery Programme, it would have been helpful for the Minister to do a review of its results. He did not.

But it is not a forward-looking Budget either. It fails to express a clear vision and, to the extent that the Lotto and Petro Caribe funds are not bought into it, and NICIL holds back public moneys, the Budget is incomplete, and not prepared in accordance with the Constitution and the law. Unemployment, the exodus of teachers and nurses, public sector pay, weak regulatory bodies, excessive bureaucracy and corruption are all overlooked.

In his usual style, the Minister boasted that the 2010 Budget is the “largest budget ever”. It is also the largest deficit ever.

In a Business Page column on the Minister’s mid-year report, Christopher Ram had indicated that he would review the performance of the key sectors in the second half of the year. The Speech and the Estimates do not allow for this. As a management tool, the Estimates is not the most useful document and the parliamentary Committee of Supplies will have a wonderful time wading through it.

While frauds take place regularly in Government Ministries and Departments, the Accountant General’s Office and the accounting capabilities of the ministries, departments, agencies and regions, earn no mention. There the money is spent.

But it suits the purpose of the Minister to talk up the Audit Office with which he has a signal conflict of interest. He must however, be aware that the Audit Office under current management will not advance. The weaknesses in the budget agencies and the Audit Office combine to make public accountability a nightmare.

The Minister exercises controls over many institutions which should operate independent of his Ministry. These include the Bank of Guyana, the Accountant’s General Department, the Audit Office, and the Bureau of Statistics. Such controls undermine the confidence which the public have in the output of these bodies.

Ram & McRae accepts that we have made many of these criticisms before.

Indications are that this will not be the last time.

Review 2009

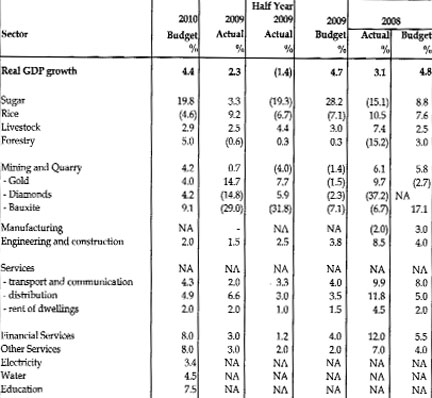

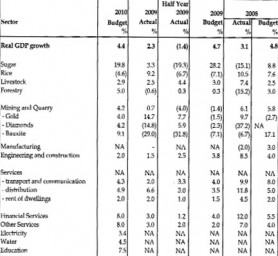

Economic Targets