Last year, Brigid Wells, a descendant of the British doctor who sailed with the first Indian immigrants to this country on the Whitby in 1838, visited Guyana. Her ancestor had written a diary about his journey here, which had remained in the family down the years, but which has now been published. She came seeking any traces of the doctor in this country; he died in Georgetown not long after his arrival, and was buried here. Roxana Kawall retraces his journey and hers.

By Roxana Kawall

A blank page in a diary drew her here, 171 years later; not the written, but the unwritten. Eighty-one years old, Brigid Wells lands in Guyana in June 2009.

The Diary is green, bound in leather, 277 pages of the cream, ribbed paper filled with the

copperplate handwriting and illustrations of the dead man whose grave she is looking for. One loose sheet, a map he drew, is folded at the front. The last date entered is April 26 in the year 1838. It is strange what fascination the artefacts of the dead have always exerted on human curiosity; a hairpin from an archaeological dig; prehistoric mother-child bones; a diary – as if within the human imagination the dead are always able to have more potential than the living.

The man is travelling towards British Guiana… In the diary he never arrives; it stops after he sails away from the “charmless Island of Ascension.”

The second to last entry written on the high seas on April 26 is a forlorn, prophetic piece of bad poetry: “My birthday! What a different sound/That word had in my youthful ears/And how each time the day comes round/Less and less white its mark appears.”

It was the last birthday he was ever to have.

The last entry, undated, comprises three words of promise and a flourish on an otherwise blank page: “Scenes in Demerara.” The following pages, about thirty of them, in the thick 7×7″ square book with the metal clasp remain empty of his copperplate.

Why? What had happened?

Ship’s doctor

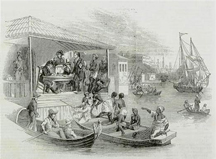

We know that his ship landed in British Guiana; we know because twelve days after he wrote his four lines of foreboding birthday poetry, between May 8 and 10, the earth of Demerara felt strange, new feet touch it; the feet of 156 Indian indentured labourers from off the sail ship, Hesperus, still alive after an outbreak of cholera on board from which he, young quite-the-lad Theophilus Richmond, ship’s doctor, had astoundingly saved them.

Three days before, the Whitby had offloaded 164 labourers in Berbice on May 5, 1838, and had proceeded to Demerara to offload another 99 between May 14 and 16. On these two ships, which had actually docked on the same day, May 5, but offloaded on different ones, were the very first labourers to arrive from India in Guiana. Young Theophilus must have felt the paparazzi were waiting for him, even back then in 1838.

It was said thirteen persons had died aboard the Hesperus. (It had actually been fifteen,

from various causes.) Magnificently timed, an article appeared in the British Guiana Gazette on the very day of the docking, speculating – against the then general background of growing moral controversy over slavery and its ilk – that two Indians who had fallen overboard had committed a despairing suicide. Indignant, Theophilus replied, but, following modern patterns, not to the Gazette, but to its rival paper, the Guiana Chronicle. He protested that these two cases had been “purely accidental.”

Suicide

Again, following modern patterns, what he said in his letter to the editor of May 7 trifled somewhat with accuracy: only one of these two man-overboard incidents had been accidental, the other Indian had indeed committed a despairing suicide, and that according to Theophilus’ own diary; but in this particular instance at least, the speculation in the Gazette was not unreasonable.

What is not clear is why he lied, why he could not simply have said: “Look I saved this man and then he went and killed himself.” Whether this was because he reacted defensively to the psychological pressure of the report in the press, or to defend his boss, John Gladstone, from the anti-slavery/indentureship feeling of the time, or whether he feared the uncomfortable fact that he was being paid a premium for every “coolie” landed alive could give rise to more paparazzi misinterpretation of his motives, or he was afraid of that which had happened on board spreading fear onshore – or whether he simply did not realise in those times his own great achievement – can now only be speculated on in yet another newspaper, some years on…

The Diary however tells how the suicide had several times begged Dr Richmond to cut his throat.

This man’s father and brother had been among the first to die on board ship – among the first of twelve the young doctor, qualified but a year before going on board the Hesperus, had been unable to save. “He himself had a very narrow escape from death also, which was greatly increased by his unwillingness to take the remedies or follow any direction that I gave him, because as he said it was never meant by his God that he was to live longer than his father and brother, and that I had committed sin and wickedness in thus preventing him from dying by making him take medicines.” He had then been put on suicide watch, but during a storm, when attention was diverted, had managed to get to the gangway and throw himself overboard.

Cholera

No descendants of this man or the others who died walk around in Guyana today. That perhaps descendants of the other 156 may be reading this today, is nothing short of phenomenal, and it is for this that Dr Thomas Pellat Richmond MD, man of his time, ambivalent figure, enamoured with life, should be remembered today.

For what had happened was that cholera had broken out on board, eight days after they had left Calcutta.

That in such an enclosed space, a death trap, out on the high seas, without access to fresh

supplies of clean water, such a young doctor had lost only twelve persons to this disease, eleven Indians and one British sailor, and had contained it within days, (possibly nine), astounds the modern mind, fed not only on descriptions of cholera in literature through the ages, but also with its recent memory of the cholera epidemic in Zimbabwe which started in August 2008 and by May 30, 2009 had reached 98,424 cases and 4,276 deaths, according to World Health Organization figures.

Richmond’s description in his diary leaves out some of the more wretched details, often described in literature. “It’s got really uncinematic symptoms. Everything comes out of every hole,” Brian Truitt, writing in The Examiner, quotes John Curran, the director of the film of Somerset Maugham’s The Painted Veil, as saying. With such immense and speedy loss of body fluids, faster than they can be replenished, no wonder death can come within hours.

Of the first case Richmond says: “At 8 oclock he was in good health walking and talking with his companions and at 1 oclock he was a corpse, a lapse of scarcely 5 hours.” Neither does he mention the smell or the grey, rice-water cloudy, mucus-flecked stool described in medical literature in the diary itself. Although cholera can come in milder varieties, the young doctor, called from breakfast Tuesday, February 6, 1838, and going immediately to this first case, realizes to his “horror and consternation” that he was looking on “cholera in one of its most aggravated shapes.”

The lone British sailor who got it “died in one of the most horrible spasms that it is possible

to conceive, his body being bent double to the very feet and his muscles knotted in all directions like a twisted piece of whipcord.”

How very nearly the 156 may not have landed in Demerara, were it not for Theophilus.

Quarantine

One hundred and seventy-one years later, Brigid Wells, on the trail of what may have been written on those blank pages, looking for closure, and wishing to see how the descendants of the people he saved had fared, stands in a classroom in Demerara giving an impromptu history class and explains how he did it. “By fumigation, segregation – and rum,” she says, waving a book. “He was my Great-Great-Uncle,” she adds.

From the very commencement of the outbreak, Theophilus, rising magnificently to the occasion and acting with decisiveness, had brilliantly had a place set apart, into which, only he, most bravely, and the sick were allowed to enter, thus cutting off all communication, and “using strong fumigations” as well. He mentions, as one of the remedies that he “employed successfully,” over a period of 16 hours giving the entire contents of a teacup of “strong Rum” to a child not yet four. Her five-year-old sister, (recorded elsewhere as ‘Meenie’) died, a sad statistic as the youngest fatality, but she survived, along with a baby and the mother. The doctor had been greatly moved by this particular family.

“It would be difficult to find a more piteous and mournful sight than this family exhibited during the afternoon of Sunday, and it was one that to the latest day of my life I shall never forget.”

He goes on to describe how the mother “would not for an instant allow” her baby, not yet a month old, to be removed from her side, and “even when lying in a state of insensibility kept fast hold of its little body,” clutching it to the breast that could not feed it, while on one side of her was one child as sick and on her other side the corpse of her five-year old, who was “already stiffening in the embrace of death, whilst to complete the picture the affectionate and wretched husband, whom neither threats or endeavours could keep away from those he loved so well, watched over them unceasingly, his sorrow speaking in his tears, and engaged with unremitting solicitude in fanning their feverish brows or moistening their pale and shrivelled lips with the cooling water they had not strength to ask for – There is no exaggeration or romance in the above scene, except as it is a romance of real life.”

It seems as if in the midst of the squalor of cholera, their filth, their sickness, their smell and their death, Theophilus’ encounter with this family was an encounter, if not personally with the numen, since he was only observer, certainly with a numinous aura shining through, which for (perhaps envious?) observers, the rare encounter with deepest human love always will have.

Disrespect

Yet this is the same Theo writing as the carefree, laddish person journeying upriver in India surrounded by birds: “I used to amuse myself occasionally by throwing first a piece of meat into the air, which was invariably caught by the Hawks before it fell, and then a hot coal which burnt their mouths and put them into a ferocious state of rage and scream.”

It is hard to know how to react to Theo sometimes.

He was obviously a man of his time, living within that paradigm, with a blithe, unconscious assumption of superiority, lover of guns and sport-shooting, (a thing his famous clergyman father, with superior moral qualities to his son, abhorred), not too enamoured with green skin (he says olive), miserable killer of birds, filled with youthful glee and the most enchanting joie de vivre, shot through with compassion and quieter moments, including rapture at “the almost unearthly magnificence of the sun sets in the Bay of Bengal,” in response to which sunsets he “could almost have fallen down and worshipped what seemed so near akin to the reality of Divinity, the Aethereal presence of a Deity.” In India he steals, on youthful impulse and adventurous whim, a small idol from a temple, a Koran from a mosque; disguises himself as a Muslim and goes into a mosque, pretending to be a worshipper, and bolts when he thinks he could be discovered, in case he was called upon for extempore prayer. Travelling down the Hoogly River towards Calcutta, the Hesperus is met by Muslim hawkers in small boats, who are discouraged by having water thrown down at them from the ship and then when that does not work, bits of pork. Richmond describes it as “a priceless bit of fun” to see their very real religious distress, “to see their energetic scrambling and tumbling over one another to avoid the accursed contamination, jumping into the river to wash first themselves and then their boats, and in less than five minutes scattered in all directions praying, swearing and crying… At the termination of this little comedy, the Captain and myself went on shore with our guns to enjoy a little shooting.”

He is obviously blithely unaware that their pain could be real or that the religious beliefs of others could have deep validity or sacredness for them, since it did not have any for him. Yet all the labourers on board the Hesperus, whom he had cared for so unhesitatingly, were Muslim, with the exception of one person, listed as a Protestant.

As said, an ambivalent person, who also describes coming across an isolated scene, as he explores the banks of the Hoogly on his way to Calcutta, which for “perfect loveliness” and “romantic beauty” and “exquisite repose” (etc!) “could hardly be equalled, certainly not excelled by any other spot on earth.”

An old Brahmin or priest was sprinkling himself, possibly in the distance by a ruined Pagoda, on steps leading down to water. Richmond falls into a sort of deep meditation: “the place was evidently sacred to one of their Gods, and was but little visited by the footsteps of strangers, as indeed it was most meet that it should not be,” he says, with for him an unusual tolerance for the sacred spaces of the religious Other. Considering that he was a clergyman’s son, and a man of his time, his spirit’s deep response to both this and to the Bay of Bengal sunsets, in contrast to his other quite different moments of superior disregard, could well, if pondered deeply, rest in the innate difference that lies between ‘religion’ and the Supreme Being, and the consequent differing response of the human heart.

In his turn, he hilariously gets the superior treatment, and from among a low caste at that, whom he calls ‘gentoos,’ who worked as palanquin bearers and boatmen, and whom he describes as “so bigoted,” that if a European even looked into their pot of boiling rice, they immediately threw it away – exactly which happened to him – since, going to get a light for his cheroot from a fire, he even dared, with the confidence of the white man, to open the lid of the ‘kettle’ on it to see what was cooking!

History lesson

Back in the Demerara classroom, the children, still standing up politely, are listening open-mouthed, and crowd around as Brigid Wells shows them the portrait of her ‘hot’ uncle, as the students and even the young history teacher dub the portrait of the long-dead man, now forever young, forever unaltered. It is his great-great niece come so many years down the line to visit him, visit the last place of his life on earth, a relative come to him at last – but with the strange tricks of continuum and dis-continuum played by time, as the eighty-one year old stands in the chiaroscuro of the classroom holding up the youthful portrait, she could very well be his fond and indulgent aunt. All of this does not feel like history. As she comments that she hopes his family and friends called him by the shortened form ‘Theo’ and not the ponderous ‘Theophilus,’ it feels like living history, or like family history. And then it begins to feel like one’s own family history. Her one-week visit to Guyana, another crossing, is already worth it. “Perhaps some of you here may even be descendants of the people he came over with,” she informs them – and all of them – for of the 156 most were men (139), some of whom later intermarried with African women, there being only six women and 11 children who landed.

The same thing happens in the staffroom and as she tours the school – she leaves a trail of connection and fascination. A former OFSTED-qualified Inspector of Schools in Great Britain, she says as she leaves: “If I lived in Guyana, I would teach here [the Marian Academy] like a shot!”

Ladies man

Theophilus would have been most pleased to hear himself described as ‘hot’ by the students – he had had quite an eye for the ladies. Amusingly, the diary is not only written at her request, but even dedicated to his “dear Mother,” apparently in the full expectation that she would indeed read its frank content. The doctor ends his dedicatory epistle schoolboy fashion, by asking his mother, one-time tutor to her children, “to cast an indulgent and not a critical eye upon the Orthography, Grammar & Calligraphy.” This clergyman’s wife (not of the Roman kind), must have been of the most liberal and indulgent sort; her son frankly regales her with his tales of lady-watching on their appearance, and his preference in (not green) all the admittedly variegated women in the countries he visited en route to Guiana, before his words disappear after Ascension Island. He tells his Mum about his admiration of long black hair; how in Mauritius he felt an overpowering inclination to kick a “Baron D’Estrente” out of the room and kiss this person’s very young wife of French extraction before he could re-enter, but refrained upon thought of the commandments; how after the women in a native village in India had fled upon his arrival, he hid “for some time behind a tree in hopes that some of the fair ones might reappear, but they smelt a rat and kept themselves close so long, that I was e’en obliged to go away and be content with this very cursory glance of the Indian ladies.” He even tells his mother how differently the nautch girls danced at an entertainment given by a Rajah after the ladies had left the room.

Nonetheless, to the students who thought him ‘hot,’ a word of warning not to neglect their studies! The young doctor, who at the beginning of his journey remarks that “a wife must be a prodigious acquisition on board a ship above all places, and I vehemently wish that I had one,” is quite critical of the way very young girls were married to older men in Mauritius. “Their education however is very much neglected, the solid and useful accomplishments of a well brought up female being sacrificed for those hollow but more showy ones, which are considered the ne plus ultra of a fashionable fair one, and the best baited hooks for a connubially disposed Gudgeon.”

He comments that few of these unions therefore turn out happy, and disapprovingly adds that the great facility for obtaining divorce under the laws of the colony, tend “still further to cast disgrace upon the sacred tie of marriage, and to render nugatory the otherwise binding vows of love.” A few pages later he cites the example of one dear little creature, “who is a good xample of the incompatibility of an early marriage with a good education.” Of her accomplished, literary (and wealthy!) husband, he muses to his mother: “Now what enjoyment can he have in such a wife, xcept just to look at and admire her, as he would a picture in an Exhibition or the Speaking Doll in the Soho Bazaar?”

Great-great niece

Dr Richmond would have been proud of his great-great niece; elegant, accomplished and accomplishing much, educated, charming, good-humoured, polite, adventurous – married with children and grandchildren, tracking him down; and without whom no one today would have heard of him or more about that distant and famous voyage as described in the little green artefact, which had somehow managed to make the journey back home all alone without him, and then ended up a jealously guarded family possession for not quite two centuries. It was however to make yet another crossing back to Guyana, albeit in mutated, or rather, evolved form.

And this is where Brigid Wells, born in 1928, enters the story, herself a multi-faceted person of many crossings.

Her own first crossing of an ocean came when she was twelve years old, in 1940, as a war evacuee from Britain to America on the Scythia, of the Cunard Line. However, for that to happen, there was first the First Battle of Newbury in 1643, and two Richmond brothers, on opposing sides. The night before the battle Henry the Cavalier heard his brother John the Roundhead was in the camp outside. Henry sneaked off to see his brother, who, upon seeing a shadowy shape at his tent in Royalist uniform, tragically killed his own brother. John, broken-hearted, then later returned to America (from where he had come back home to join in the Civil War) – yet another family crossing. Down the line, Brigid’s mother, Susan Richmond, a famous actress and author of apparently what may have been one of the first books in the UK to try to teach the craft of acting, Textbook of Stage Craft, and who had also been a nurse in France in WWI, had received a telegram from the descendants of John the Roundhead – relatives in America who had offered to take Brigid.

Exile

Brigid reports, rather dramatically, that her mother was not allowed to go further than the barrier on the docks, and that was the last she saw of her mother for four years. A few days later, Susan saw a newspaper headline opposite her in the train, saying that a ship carrying children had been torpedoed. What she did not know, as she grabbed the paper, was that it was not her daughter’s ship. The Scythia had not left immediately, but had actually spent several days in port waiting for a protective convoy before it had sailed. Brigid remembers that after their escorting destroyer left, someone asked the Purser: “What do we do now?” “We run like hell!” the Purser replied.

During her four years away, Brigid’s education was a trifle peculiar in terms of chronology; she did Form Two, Form Three, then was sent to Canada, where as a British 14-year-old, her level was the same as that of the Upper Sixth which she attended with the 17 and 18-year-olds. She then returned to the US to do Lower Sixth at the prestigious Masters School, which is currently headed by a Guyanese, Ms Maureen Fonseca-Sabune. One week before she was due to graduate (yet again), she was offered passage home on a troop ship. She went, missing the graduation, but still remembers someone’s old bridesmaid dress which had been altered for her as a graduation dress. “It was very odd getting on the train in Liverpool,” she says. “I had left as a schoolgirl with a bob, and I was back with lipstick and a hat.” She notes that mail took a month to six weeks to arrive, so if she had had a problem, there was no immediate answer. She remembers her doctor father, who two months before the war had signed up in the Royal Army Medical Corps, writing her at fourteen: “Kissing is all very well, but nothing else.”

Back in war-time Britain, Brigid dodged Doodlebugs and V2s, went on tour with her mother, attended Edinburgh University for one year. She then read History at Oxford, took the Civil Service exam, worked in the Commonwealth Relations Office, was posted to New Zealand as Second Secretary (where she drove a little Morris Minor, “very smart, a black convertible with red seats, marvellous at holding the road”), then had two years as Private Secretary to the Parliamentary Undersecretary of State. She would then have been posted to India, but her then boyfriend said: “If you go to India, I won’t see you again.”

“I couldn’t face the agro,” she confesses, so she asked for a transfer to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food – apparently, since one could see the results, much more rewarding work than the Foreign Service! “I was twenty-eight and had men of forty-five under me,” she adds gleefully, noting that although women worked as secretaries, etc, at the time, not many had positions of responsibility in the civil service.

Comprehensive school

In 1961 she met her future husband, Ian, playing tennis. After marriage in 1962, she resigned, but only a few months after she saw a notice that led her path into teaching. Among those varied teaching experiences was one she calls a baptism of fire, when in 1975 she thought she should get some comprehensive school experience – a lot of racism and violence. Regarding exam results at the comprehensive, she notes that out of 250 entries, there would be something like three maths passes. However, in a sort of female To Sir with Love incident, she got 27 out of 28 children through Religious Education. One Caribbean girl, whom Brigid describes as “very naughty,” was so proud of this, her one ‘O’ level, it inspired her to go to night school and then to university and she is now a head teacher, still in touch with Ms Wells. From the comprehensive Brigid became Head of Brighton and Hove High School, where she notes the behaviour was much better: “O I was floating!” she remarks. She soon got into other ‘sidelines,’ which included being a magistrate – apparently she found dealing with petty crime, minor theft and drunkenness “fascinating” – as well as being a member of the Broadcasting Complaints Commission (OFCOM), and a Chairman of the Selection Board for the Fast Stream for the Home Civil Service and Foreign Service. She then qualified as a school inspector; “Very gruelling,” she grins. “I did the last one when I was 75. I thought, really, staying up all night and writing reports was too much.” Not long after, however, in 2005, she was to see a programme on television.

It was on the Indian diaspora, the British sending Indians to Fiji and East Africa, and the results thereof, by Dr David Dabydeen of Warwick University. She was to remember then an old green diary she had read when she was about forty years old.

“My much older cousin John Bell was very interested in family history. And very protective of it. He married late; was austere, rigid in his thinking. Family stuff was sacred – to research, look at – but not outside the family. He lent me the diary to read, and I photocopied it, but he didn’t know. At that time there weren’t too many photocopying machines around; I got a don at Cambridge to do it. At the time I thought it a good travelogue; I suggested publishing, but John said no. He died in 2001. After David’s programme I got in touch first with John’s daughter, Melinda Diamond, a practice nurse, and then her mother, to ask permission. I wrote to David and asked if he was interested in reading it; he said yes, send him the text. I spent a long time typing all the pages! After David read it, he recognised it was the Gladstone shipment…”

Return

As soon as the question of publication came up, Melinda Diamond gave her permission. Theophilus’ diary returned to the land of his death in 2007, with, so strangely, additions to it by his own great great-niece, namely Parts One and Two of the Introduction to The First Crossing by Theophilus Richmond. (Ed David Dabydeen, Jonathan Morley, Brinsley Samaroo, Amar Wahab and Brigid Wells. – The Derek Walcott Press.) In a way it was as if those blank diary pages were filled in (not those at the back, but those at the front) of what had happened to him after his words stopped – the before, of who he was.

In 2009 Brigid was at a launching in Warwick, where someone, she suspects Clem Seecharan, noted Guyanese historian, half-jokingly repeated a suggestion to Dr Dabydeen that had been made before: why didn’t he take Brigid to Guyana? Dr Dabydeen said he was going there in two weeks. Brigid says she spent a week thinking about whether she dared do it… At 81 years, if she did not do it now she never would. She made arrangements for her husband’s care, cashed in her savings and came for one week, hoping to find where Theophilus was buried, and where the house of the Acting Government Secretary, W.B Wolseley, where he had died, was in ‘Vlissingen,’ the frontlands of which stretched from Bourda to Stabroek, according to an 1824 map.

All that is left of Theo after his birthday poetry is his letter to the press and one to Sir John Gladstone, his boss who owned the plantations in Guiana to which the Indians were being shipped, published in the Parliamentary Papers in Britain. To the latter letter he had attached a medical report, which contained the less salubrious details of the cholera which had not been mentioned in the Diary.

An obituary in the Royal Gazette of British Guiana records the death of the “amiable and cheerful” Theophilus Richmond, youngest son of the late Revd Legh Richmond who, among other duties had also been Chaplain to His Royal Highness the late Duke of Kent [father of Queen Victoria], on 5 July 1838, exactly two months after Arrival Day. Theophilus Pellat Richmond, so enchanted with life, he who had saved the Indian labourers, had died from the yellow fever he could not save himself from and from which there had been no one to save him. He was twenty-three.

But all that Brigid finds is an entry in the Anglican records, stating he was buried by the Vicar of St George’s Church (predecessor of the cathedral) on July 6; old houses are gone, and as she points out, who would have paid for a tombstone.

Walking past the old Bourda cemetery, with invisible graves masked by waist-high grass and tomb-high rubbish mixed with faeces and the pervasive smell of human urine, reminiscent of the mournful cholera scenes, “the first that I have ever written of its kind, and God willing not the first only but also the last,” one hopes with great sadness that Theo is not in there.