In last week’s column I began by introducing the sixth and final of the basic contradictions, which as I have argued underlie global multilateral negotiations on climate change. I had advanced the proposition that at every stage of the negotiation process one or more of these basic contradictions would unfold leading to the systematic undermining and disruption of global efforts to generate solutions. As noted, the sixth contradiction refers to the progressive worldwide tendency to commercialize approaches towards finding global solutions in the belief that the private market and for-profit enterprises hold the key to a permanent and successful resolution of the problems of climate change and global warming. As I also pointed out the LCDS is similarly premised on the eventual creation of a global private market in which carbon forests payments will be made in exchange for keeping Guyana’s forests standing.

At present the principal initiative for negotiating the role of forests under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is the Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD) programme. This has been subsequently expanded to the REDD- plus programme. Together they seek to provide a system in which payments are made in return for the effective preservation of existing forests, sustainable forest management, the conservation of existing carbon stocks in forests, and their enhancement. Actually the REDD and REDD- plus initiatives do not rely exclusively on private markets to provide payments for the delivery of forest carbon services. Conceptually and practically they also accommodate for public payments to be made into a “climate fund” or for that matter a mixture of both public and private funding.

At present the principal initiative for negotiating the role of forests under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is the Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD) programme. This has been subsequently expanded to the REDD- plus programme. Together they seek to provide a system in which payments are made in return for the effective preservation of existing forests, sustainable forest management, the conservation of existing carbon stocks in forests, and their enhancement. Actually the REDD and REDD- plus initiatives do not rely exclusively on private markets to provide payments for the delivery of forest carbon services. Conceptually and practically they also accommodate for public payments to be made into a “climate fund” or for that matter a mixture of both public and private funding.

Forests and carbon services

Forests provide a wide variety of environmental services, such as watershed protection, conserving biodiversity and protection from landslides and floods. The focus, however, has been on their contribution to what is known as carbon sequestration. This arises because forests have a two-fold effect on carbon dioxide (CO2). First, when forests are cleared or degraded they release carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere, thereby leading to climate change and global warming. Second, when forests are left standing or managed in a sustainable way so as to avoid their destruction, they provide carbon sinks that help to absorb carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted into the atmosphere. Indeed, it is estimated by environmental scientists that global forests (including all their vegetation and soils) hold about 40 per cent of the total amount of carbon stored in the earth’s ecosystems.

Forests occur widely, in both the northern and southern hemispheres. Most of the stored carbon in forests has been estimated to lie in the northern hemisphere. The current estimate is that when re-growth of the northern forests is taken into account they are a net absorber of carbon dioxide (CO2). This makes these forests a net carbon sink. On the other hand, tropical forests are being subjected to such intense removal, clearance, and degradation that they are currently a net source of carbon emissions. For further details/information readers should consult the Encyclopaedia of Earth or the Food and Agricultural Organization’s (FAO) The State of the Worlds Forests.

Readers can glean from the above why it is that REDD and REDD- plus have turned out to be one of the most hotly debated agenda items in the climate change and global warming negotiations. There is contention in regard to 1) who should be rewarded for keeping forests sustainably managed. (Should it be the central, local, or regional governments where the forests are located; private forests owners, whether large, small or transnational; or indigenous peoples and other communal forest owners?); 2) how to measure, monitor, report and verify which forest practices are sustainable, additional and permanent; 3) how to finance these payments.

I will attempt to clarify these issues as we proceed, but my main intention at this stage of the discussion is to emphasise the controversial nature of the REDD and REDD- plus forest initiative and the many complex and practical problems involved in the determination of how best to secure the contribution of forests environmental services towards resolving the impending crisis of climate change and global warming.

Forest losses and gains

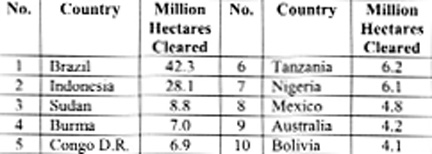

Global data on net forests loss are very revealing. The FAO and World Resources Institute (WRI) estimate that for the years 1990-2005 the ten countries with the greatest net forest loss are shown in Table I. The largest net forest loss comes from our neighbour Brazil (42.3 million ha). The top ten countries with net forests have cleared a total of (118.5 million hectares of which Brazil alone accounted for well over one-third and Indonesia about one-quarter.

Table 1: Net Forest Loss, 1990-2005

Source: World Resources Institute (WRI).

Source: World Resources Institute (WRI).

On the other side of the coin their data show that for the same period the five leading countries with gains in net forests planted (million hectares) are China (40.1); Spain (4.1); India (3.8) Italy (1.6) and France (1.0).

More generally, the FAO found that recently there has been overall progress in forest management, albeit unevenly. In the developed industrialised economies with temperate forests significant progress has been reported. Forest areas have been stable or increasing. On the other hand in the poor countries and tropical forest areas acreage has been on the whole declining.

Next week I shall begin by reflecting on the reason for this very different performance as it has direct consequences for the LCDS, which as we shall see seeks to treat Guyana as an exception to the typical pattern of poor country/tropical forest area outcome.