There appears to be a simmering argument between the Ministry of Education and the Teaching Service Com-mission over the issue reported as ‘Over 150 teachers fired last year’ (SN, March 4) and ‘Education ministry supports TSC…’ (SN, March 10). While the ministry rightly agrees with the sackings, it argues that the TSC has the sole responsibility for the appointment and dismissal of teachers, except in those schools that have their own boards, and seems to be suggesting that, as such, the TSC has some responsibility for the issue of teacher rationalisation.

I recognise that my agreement with the TSC decision may well be based on an over-simplification of a situation pregnant with difficulties. After all, myriad negative implications may be contained in the fact that 154 teachers represent some 1.7% of the total teaching population of 9,303; 3.4% of trained teachers (4,523) and some 50% of teachers trained each year, and the numbers provided by the TSC (or your writer) do not help us to fathom whether this level of dismissal was part of a rationalisation programme or whether we should expect similar numbers in future years. We also do not know who these teachers are in terms of qualifications, regional location and other characteristics and have been given no idea as to how the 2009 figure compares with those of previous years or whether the TSC has introduced new disciplinary rules or has simply decided to become more active.

The TSC could have fired the teachers and stayed quiet about it, but from the various statements made, it would appear that it discerned a concern about teacher discipline and went public to convince us that it is now on top of the problem at the same time is sending a message to teachers to shape up or ship out. Be that as it may, when I am confronted with this kind of bald presentation, what immediately comes to mind is our willingness to allow officialdom, both private and public, to frame and perpetuate public discourse and perceptions to suit themselves. Because of our reluctance to go much beyond what is presented, we are many times left with quite distorted notions of reality. As an historical illustration, since we are dealing with the education system, consider the table and comment below, taken from a 1964 report on education in Guyana, by the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.

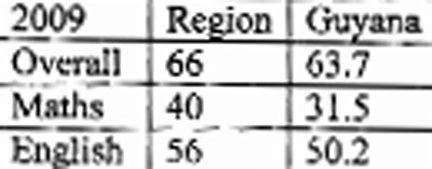

Examination Results, 1961

Includes 150 pupils of the 4th form who take 1 or 2 subjects only.

Includes 150 pupils of the 4th form who take 1 or 2 subjects only.

Report of the UNESCO Educational Survey Mission to British Guyana (1964)

“The considerably better showing at the Oxford and Cambridge examination, the examination taken by the 5 older schools, is proof of their marked academic superiority. The London and Cambridge certificate figures make dismal reading… The significant fact is that the school system in 1961 provided at the most 247 candidates with the minimum qualifications for entry to the University of Guyana. If we add those with passes in 4 subjects, then we have a total pool of 501 for the university, for pre-service teacher training, for the 6th forms and for commerce, industry and the public service.”

Bearing in mind that education outcomes do not normally change radically from year to year, what do we mean when we continually speak of our glorious education system of the 1950s and early 1960s? Yet this myth is still being perpetuated by our mass media and even the international community. Today, the total number of candidates taking the CXC has doubled and instead of about 5%, some 20% gain 5 and more subjects.

Compared with today, we may have then had a better primary system, bearing in mind that in 1960 3.6% of the national income and 14% of government expenditure went to education and the vast majority of it – $5.4M out of $8.1M – to primary education. Secondary education received about $.7M. From a population of 582,200 in 1961, primary enrolment was about 130,202 and average attendance was 83%. In 2006-7, with a population of about 760,000, we had a total primary population of 118,000 and 80% attendance (the numbers include about 11,000 in the secondary departments and many other factors, including the wider availability of secondary education, may account for the differences between periods). Is it that even for the 1950s the idealised reality was merely propaganda or am I wrong?

It matters not whether we are dealing with the city council, sea defence or the health or education systems, when presentations focus on the operational and procedural rather than the substantive issues (the rationale for taking action, the inputs available, outcomes expected, timeframe, etc) we should be on guard. Public officials provide idealised notions of what is achievable given extremely limited resources and then fill the void between the expectations they have created and reality with propaganda and machinations.

For example, the current ideal says that given the “vast” amount of resources that the government is putting into the education system, Guyana should be achieving similar results to those in the rest of the Caribbean, that the results are bad largely because of bad management (ie, there is not sufficient value for the money!) and that the blame lies with the managers of the education system and not with the political system. Careful analysis will however show that this is not the essential truth.

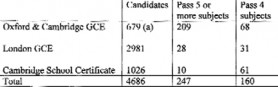

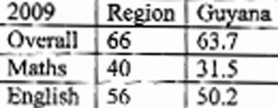

Guyana spends about US$200 per child on primary education, Barbados US$3,000, Trinidad and Tobago US$2,500, Jamaica about US$850, St Lucia around US$800 and so on. (In passing, it may be useful to note that government spending on education has been reduced from 9% of GDP and 18% of government expenditure in 1998 to 6% of GDP and 12% government expenditure in 2007 (UNESCO:WDI). This is certainly a comment on the priority of education in the general scheme of things and it is no wonder that, notwithstanding the commendable achievements of some individual students, Guyana has consistently been below the regional average where GCSE results are concerned.)

GSCE Grades 1-3 passes: 2009

Our most qualified and experienced teachers leave Guyana largely because the pay and conditions are better elsewhere. Teachers are only one factor in the scheme of things, but their very movement reflects its condition. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, my contention is that given the resources at its disposal, the system has been performing reasonably well. As a matter of fact, an analysis of the performance of some of our better private schools may be most instructive in helping us to better understand the economics of education.

Our most qualified and experienced teachers leave Guyana largely because the pay and conditions are better elsewhere. Teachers are only one factor in the scheme of things, but their very movement reflects its condition. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, my contention is that given the resources at its disposal, the system has been performing reasonably well. As a matter of fact, an analysis of the performance of some of our better private schools may be most instructive in helping us to better understand the economics of education.

We would consider a man who earns the minimum wage but wants to live in a $50M house a dreamer, yet dreaming is precisely what we do in relation to this and many other issues. A manager should always be encouraged to get the most from any given level of resources, but there is a limit, even if a gradually expanding one.

The real question is why we have so little to spend, why of what we have a greater portion is not being allocated to the education system and what results can we realistically expect from the given allocation? These are not operation/procedural questions but uncomfortable political ones, and therefore the blame is shifted to management. Doing so however only adds to our difficulties, for if we do not develop realistic benchmarks, if we exaggerate our possibilities and then blame the managers for not achieving them, the disillusionment and self-doubt that must follow will themselves impact negatively upon our goals.

Yours faithfully,

Henry B Jeffrey