It is an overall positive statement about the state of dance in Guyana when the achievements of the growing numbers of dance companies are put on show. This may be so because regardless of the quality of the exhibitions, the fairly recent growth of these groups and the capacity of some of them to sustain a series of full-length dance productions for public scrutiny is a positive signal. These groups have been able to emerge because most of them are set up and run by individuals who are among the large number of trained dancers now to be found in Guyana. The overall statement is that the country can now see the benefit of the investment that it made in the training of dancers.

A further statement being made about dance is not only about training, the escalated numbers of dancers, dance teachers, groups and full productions, but about the audience for dance. The most recent development has been the creation of a fairly new and popular audience for dance in Guyana whose growth has been symbiotic with the corresponding rise of popular dance. This is an important development for which there is praise and a question.

A further statement being made about dance is not only about training, the escalated numbers of dancers, dance teachers, groups and full productions, but about the audience for dance. The most recent development has been the creation of a fairly new and popular audience for dance in Guyana whose growth has been symbiotic with the corresponding rise of popular dance. This is an important development for which there is praise and a question.

The latest revelation of these dynamics in popular dance came with the most recent production by the Classique dance group titled Scandalous. It demonstrated several factors about a new popular interest in dance, about the positive results of the investment in training and about a few developments that are laudable achievements; however, there were a number of notes of caution, if not of sacrifice.

Scandalous was a reminder that the kinds of debates which still persist about the value (or perceived lack of it) of the popular play also apply to popular dance, which has now taken on new dimensions in this country. First of all the title was an obvious ploy to sell tickets. It worked. Yet the fact that it could work so well, with two absolutely sold-out shows at the NCC, indicates that there is a ready audience for this kind of theatre. The fact that they were well entertained and understood what they were looking at says a bit more. This is a new wave; very large numbers of young enthusiasts who now go to the theatre to see dance. They have changed the older trends where a small number of the older elite appreciated dance. Now there is a young popular crowd who are thrilled by popular dance.

Classique knows how to communicate with this audience. Among the good things about this is that the group has developed interesting stylistic techniques to cater to their audience. They have also gone up considerably in critical estimation because their previous shows were not quite good and did not always live up to expectations.

However, having responded so well to the audience and the communication that they have created, they then had to sustain the interest. The questions arise because what Classique has come up with incites genuine critical interest but definitely shows that some sacrifice has taken place. The production was high on entertainment but somewhat low on depth, thoroughness and thematic concept. It attempted an adaptation of sequences from a well-known movie which was sometimes superficial and allowed comic entertainment to interfere with pathos.

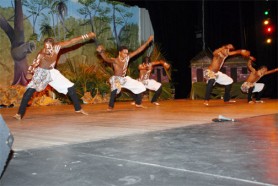

The group is led by Clive Prowell, one of the corps of trained dancers out of the National School who then went on to form companies and train many others. The performance in this production was lively, up-beat and overbrimming with boundless energy. It was delightfully uninhibited, dynamic and seemingly the end-product of a great volume of work. To the credit of Prowell and his group, they had on show in this production, apart from good female leads such as Leslyn Lashley, the largest company of competent male dancers in the country. One of their strong points is acrobatic techniques and there is one of the lead males who is excellent in this area in which he demonstrated outstanding acrobatic skills.

The first half of the production was mainly the adaptations from The Lion King which was mixed. The most interesting thing about it was the stylistic dimension. In the middle of the popular and the modern there was something of the classical. This was first signalled by the appearance in the first movement on stage of dancers en pointe, showing an intrusion of the classical in what they wanted to do. The remake of The Lion King was mainly done in modern ballet against a very spectacular jungle set. These added value to the work and the imagination.

However, it was not all entirely clear. Always in an adaptation, knowledge of the original is very helpful, but the new work must be able to stand on its own. This one was not so able and depended too much on one’s knowledge and memory of what happened in the film. That dependence is a feature of the popular performance and contributed to the superficiality and lack of depth, since no additional statements were being made. In the attempt to reproduce the plot there was a resort to a great deal of mime for which dance was too often sacrificed – a few things were acted out and mimed to the words of songs, not interpreted in dance. Also, some parts of it required pathos, but this was spoilt by comic inputs to entertain, and while humour was another good point of the performance, these comic inputs at times killed off the pathos and diminished meaning.

There was one Lion King sequence that stood out in dance and achievement, depicting the return of the ‘prince’ to his home to find the results of killings and destruction. That dance was all-round clarity and neatness, achieving mood and pathos in which the lead male was very well supported by the chorus. In a number of other sequences the modern ballet was reminiscent of the Broadway style and chorus line, while in others there was untidiness, ragged lines, weak formations and some uncertainty in costuming.

Most things worked better, and there was more success in the second half of the production with its variety of individual dances. One could make more sense out of the style of the production with its interpretive modern types of popular work. Some of the pieces were still nondescript, but others stood out as pieces in which the dancers understood the styles and the theatre of performances expected of them. These gave the show some meaning and made a statement out of Scandalous, which became more than just a popular gimmick. It could then apply to the uninhibited jazzy modern style in which things were done.

The most successful example of this was the choreography to Rihanna’s Russian Roulette. This was modern interpretive dance in an interesting, effective and highly theatrical performance in the post-modernist and even absurdist trend. These types were appropriate for the mood and clarity of meaning; quite convincing that one was about to ‘pull the trigger’ either in the madness of a grotesque game or out of the mental, emotional disturbance and the anguish of internal conflict communicated by the dancers. The piece had excellent female leads well supported by the rest of the cast in a dramatic setting and tableau. It had impact and social relevance reflecting a troubled society which could support the grotesque in bizarre games, or in which suicides abounded. Choreographies like this gave relevance to the notion of “scandalous.”

In another well-articulated dance in a similar trend, there were very effective images of sexuality with sensual body language, costuming and movement. It was dances like these that made the show interesting and worthwhile. These were examples of how the group was able to make something out of popular dance which entertained the audience, while creating something engaging and formally worthwhile. A good deal of what it takes to make good dance was sacrificed for the sake of the popular, but at the same time the group made a creditable attempt to craft performing styles that recommend them as a group that has undoubtedly improved.