Introduction

In the previous column, I argued that the relative stability of the exchange rate since around 2004 could be the result of moral suasion, which implies the authorities persuade the price leader – the trader which dominates the exchange rate formation – to set rates in line with the social objective of price stability. I also explained why the largest foreign exchange (FX) traders, the commercial banks, might want to cooperate with this strategy. Namely, I noted that banks with large Guyana dollar loan portfolios would be more willing to cooperate given that in an inflationary situation they stand to lose on loans when the real interest rate turns negative and the principal on loans erodes in real term.

No doubt there is also a political economy (the interaction between economic and political systems) dimension to this seemingly fixed rate strategy; namely the stable exchange rate helps to promotes price stability and therefore less adverse impact on cost of living. In my opinion, Guyana’s emerging oligarchic structure (which I must analyze in future columns) would find a fixed exchange rate attractive. As an aside, an oligarch represents a small group of people who have both economic and political power; the economic power, furthermore, reinforces the political power.

In the case of Guyana, defending a virtually fixed rate is made less complicated because of the nature of capital inflows. Guyana is not susceptible to the destabilizing inflows of short-term money (or hot money) inflows that have caused financial crises and the collapse of pegged exchange rate regimes in several parts of the world. These short-term funds are not important for Guyana because there are not many avenues in the underdeveloped domestic financial system in which these funds can find investment channels. Instead, capital inflows come mainly in the form of foreign direct investments, long-term concessional loans, and altruistic remittances.

Under reporting of non-bank cambios

One comment I have elicited from the previous column pertains to the potential underreporting of foreign exchange trades by the non-bank cambios. While I am sympathetic to this point, I have to work with the official data reported. Should there be full reporting by the non-bank cambios, I still do not believe it would be sufficient to displace the commercial banks as the largest traders. In Jamaica, for instance, non-bank cambios account for approximately 30% of trades (while in Guyana it stands at around 10%). Nevertheless, this could be a fertile ground for economic researchers a UG; anecdotal evidence, while helpful, is never a substitute for deep economic analysis.

One view is that hard currency proceeds from the underground economy flow through the non-bank cambios at a greater extent than the bank cambios. It is not easy to establish the latter view; and it is not necessary for that to hold. Nevertheless, a recent paper by Professor Thomas and two co-authors (Sukrishnalall Pasha and Natoya Jourdain) updated the estimates for Guyana’s underground economy. They found a large spike in the size of underground economy in 1994 and a gradual decline from 2005. Exactly how the foreign currency proceeds of this sector are distributed among the cambios could be subject for interesting research. It should be noted that over the period of the consolidation of the pegged exchange rate the underground estimates, according to Thomas et al, amounted to 40.5% (2006), 36.8% (2007) and 31.7% (2008).

The real exchange rate

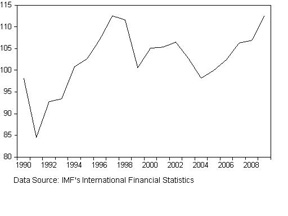

Although the nominal exchange rate has been relatively stable in the past few years, the real exchange rate could appreciate or depreciate. The real exchange rate is the ratio of Guyana’s price level to that of her trading partners. To a large extent the real exchange rate determines the competitiveness of exports. Figure 1 shows the real exchange rate from 1990 to 2009. The upward trend indicates a real appreciation of the Guyana currency (from the IMF statistics decrease in the index signals depreciation while increase in the index signals appreciation). Given the appreciation, Guyana’s exports are becoming less competitive. The figure, moreover, shows that the appreciation picked up steeply since 2004 – a period from which we noted in the previous column the nominal exchange rate began to stabilize.

Figure 1. Real Exchange Rate – 1990 to 2009

The academic literature recognizes that a real appreciation could add a burden to nascent and existing export sectors, thereby making the structural production transformation of the economy more difficult. Readers would realize that these columns advocate an upgrade of Guyana’s production to more valuable products; as noted in past columns a country is as poor as what it produces. In addition to an uncompetitive real exchange rate, producers face high electricity costs, high interest rates, limited capital market development, a security system which lacks credibility, shortage of skilled and educated workers, and primitive physical infrastructure.

Fixed versus flexible rates

An important question which needs to be addressed is whether the nominal exchange rate should be allowed, in the present period, to depreciate to maintain export competitiveness by causing the real exchange rate to depreciate. I would say this is not essential for several reasons.

First, Guyana presently has little new products to sell to the rest of the world. In the future however as policy makers become serious about production transformation it becomes much more essential to allow for a competitive exchange rate. Second, given the primitive production structure, the poor will be adversely affected as the exchange rate depreciation passes through to consumer prices; in other words, a worsening of the cost of living.

Third, there is always a feedback from exchange rate depreciation to inflation given that Guyana imports most of what it consumes. Thus depreciation in the nominal exchange rate could lead to an increase in the price level. This could engender macroeconomic instability and capital flight. Fourth, several Caribbean economies such as Barbados, The Bahamas and countries within the ECCU have achieved a substantial degree of economic progress using fixed exchange rates. These societies have made tremendous sacrifices to maintain fixed exchange rates. For instance, Barbados workers accepted wage cuts in the early 1990s in order to defend the fixed rate.

Fifth, given the nature of capital inflows in the form of altruistic remittances, long-term concessional loans and limited foreign direct investments, Guyana could still pursue some form of independent monetary policy. Independent monetary policy is particularly made difficult when flows are short-term or hot money flows. These short-term inflows can suddenly flow outward and in the process precipitating a financial crisis. However, these short-term flows are virtually non-existent in the Guyana context. It is also one of the reasons why Guyana was shielded during the recent global financial crisis.

I would like to end this series by noting that I am sympathetic to and supportive of the recent policy of nominal exchange rate stabilization. In the next set of columns, I intend to examine the rise of an oligarchic political structure and its implication for economic development.

Please send comments and criticisms to: tarronkhemraj@gmail.com