Amerindian influence on settlers

The Amerindian people were the first inhabitants of Guiana. Guyana Review reprints this essay by Vincent Roth that was first published in Kyk-Over-Al – one of this country’s most respected journals.

By Vincent Roth, OBE, JP

One’s first reaction to the question, what was the influence exerted by the Amerindians upon the subsequent settlers of Guiana and their descendants, would be to say “None. Rather, the other way about.”

For, undoubtedly, the influence of the subsequent European and African arrivals in Guiana upon the indigenous inhabitants has been, if not exactly disastrous, at least not too beneficial. True, they put an end to inter-tribal warfare; they introduced to them the mysteries and benefits of civilization. But to what ultimate good!

The hundreds of thousands of original inhabitants have been reduced to a mere fifteen thousand at the present time. Even in quite recent times, certain tribes who lived under what may be termed pure communism in which all property was held in common, had no conception of the meaning of theft. It was the missionaries who opened their eyes to this concomitant of so-called civilisation.

Now, let us look at the other side of the picture – the influence if any of the Amerindians upon their would-be teachers and undoubted exploiters. This influence was almost wholly of a material nature.

When Columbus came to the Americas for the first time, he found the “hanging beds” or hamacas used by these people. The Europeans did not take long to appreciate the usefulness and comfort of the hammock which before long became not only an indispensable piece of furniture in the new settlers’ homes but, eventually, was adopted by the Royal Navy. When the Dutch first arrived in Guiana to trade with the Amerindian, they made more than a good thing in trading their goods for hammocks, some of which were valued as high as twenty pounds.

From the Amerindians they also got the red vegetable dye annatto which, until the discovery of the aniline dyes, was a must in every well-appointed kitchen. They also learnt the value for furniture and ornament-making of some of the local woods, especially the peculiarly marked letter wood, in which quite a big trade was done.

From the Amerindians the settlers learnt the use of cassava – both sweet and bitter – and its derivative, the wonderful meat preservative, cassareep. With regard to cassava, it was fortunate for the newcomers that they arrived here after the Amerindians had discovered the method of rendering edible the highly poisonous bitter cassava and it may safely be assumed that some mistakes were made at first with fatal results, as happens occasionally even to this day when someone mistakes the bitter for the sweet cassava and cooks and consumes it.

The discovery of preparing bitter cassava for food in the form of bread, farine, flour and tapioca must undoubtedly have been made by trial and error – and imagine the number of persons who over the years must have been poisoned by the errors. One of the most important results of the discovery was that of boiling the poisonous juices extracted from the pulped bitter cassava until it was converted into the viscous brown fluid known as cassareep, the basis of the popular dish – pepper-pot – for which originally we are also indebted to the Amerindians.

To them also we owe that delightfully crisp wafer-thin cassava bread which, lightly toasted and buttered, occasionally forms such a welcome portion of one’s afternoon tea. This, of course, was developed from the half-inch thick three-foot diameter circular disc of the original native cassava bread. When the Rupununi ranchers go out on the trail, they thank the Amerindians for the tasteless but nourishing farine, a coarse gravel-like flour derived from the cassava. Boiled with tasso – as the local sun-dried beef is called – it is quite edible and even tasty.

Whilst there is no proof that the sugar-cane is indigenous in America, it nevertheless can be found in the remotest Amerindian settlements and of types never now seen on the plantations. These canes probably developed from cuttings obtained from the early settlers. Accustomed, as they were to making fermented sweet drinks from the local cashew and other indigenous fruit, the Amerindians soon found a method of fermenting the cane-juice into a highly potable and pleasant beverage known as waraap. Its manufacture was quickly adopted by the settlers, whose present-day descendants in the river districts make full use of it.

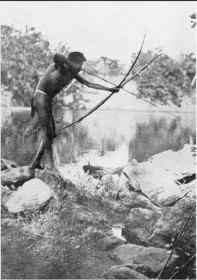

Perhaps one of the greatest debts owed to the Amerindians is one not generally recognized. But for their piloting, no boats could have surmounted the numerous falls obstructing all river routes to the interior of the country and, but for their skill, it is doubtful whether the development of the interior, such as it is, would have reached the stage it has.

It is interesting to speculate on how the first five-ton gold and diamond-digging boat was first navigated down the falls. Going up would be comparatively easy, being a question merely of hauling the craft by main force over the rocks. But rushing down between the jagged rocks, visible and invisible, at a speed of thirty to forty miles an hour where the slightest error in handling the craft would have fatal results – was quite another matter.

Often have I metaphorically taken off my hat to the original Amerindian pioneers who performed this feat. No doubt they first attempted it with dug-out canoes and, as they gained confidence, used gradually larger craft. Extant photographs of river boats of seventy to eighty years ago show that they were but half the size of those used today. Indeed, the Schomburgks and other early travellers on our interior rivers seem to have depended mainly on very large dug-out canoes. Nevertheless, but for the navigational skill of the Amerindians, it is questionable whether these journeys ever could have been made.

Although we have learnt much from the Amerindians about the medicinal properties of the various seeds, barks, roots and leaves of the forest flora, including the terrible curare poison now proving so useful as an anaesthetic for certain major operations, there is still much room for research in this line. The most knowledgeable among the Amerindians in this respect are the piaimen or medicine men who, naturally, are not keen to disseminate their professional knowledge.